MINDSPACE Framework

What is the MINDSPACE Framework?

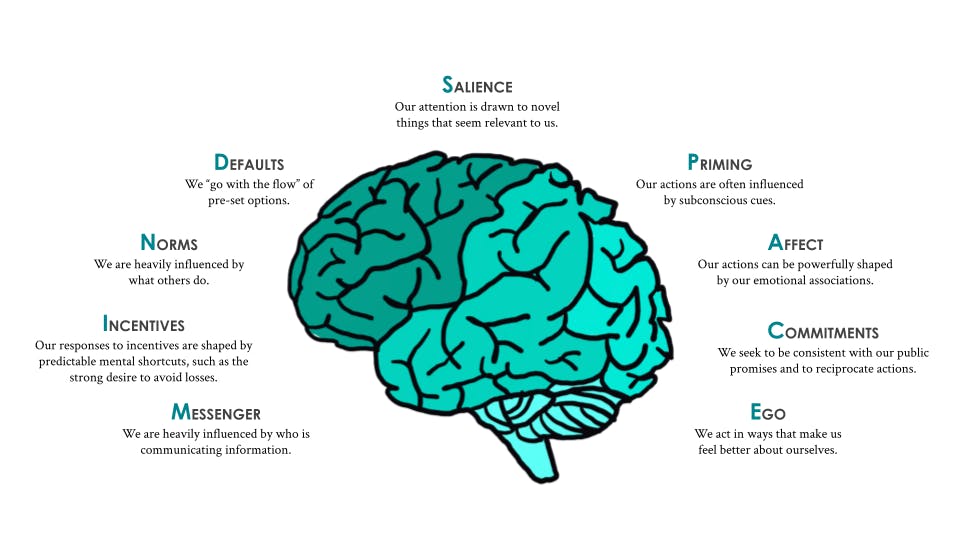

The MINDSPACE framework is a tool used to integrate principles of behavioral science in policymaking. It highlights nine important factors that drive behavior: messenger (M), incentives (I), norms (N), defaults (D), salience (S), priming (P), affect (A), commitments (C), and ego (E).

What is a Framework?

Behavior change frameworks are the bedrock of applied behavioral science. Designed by behavioral scientists for policymakers and industry leaders, these summaries of cutting-edge decision-making insights are essential for applying research in the public and private spheres. Frameworks distill strategies for influencing human decisions into simple, portable mnemonic devices or acronyms. This makes it possible for complex, theoretical insights about how people think and act to make their way into the practices of organizations across every industry and environment. To understand more about how these frameworks work in practice, check out our case studies.

About the Author

Kira Warje

Kira holds a degree in Psychology with an extended minor in Anthropology. Fascinated by all things human, she has written extensively on cognition and mental health, often leveraging insights about the human mind to craft actionable marketing content for brands. She loves talking about human quirks and motivations, driven by the belief that behavioural science can help us all lead healthier, happier, and more sustainable lives. Occasionally, Kira dabbles in web development and enjoys learning about the synergy between psychology and UX design.