Why do we take mental shortcuts?

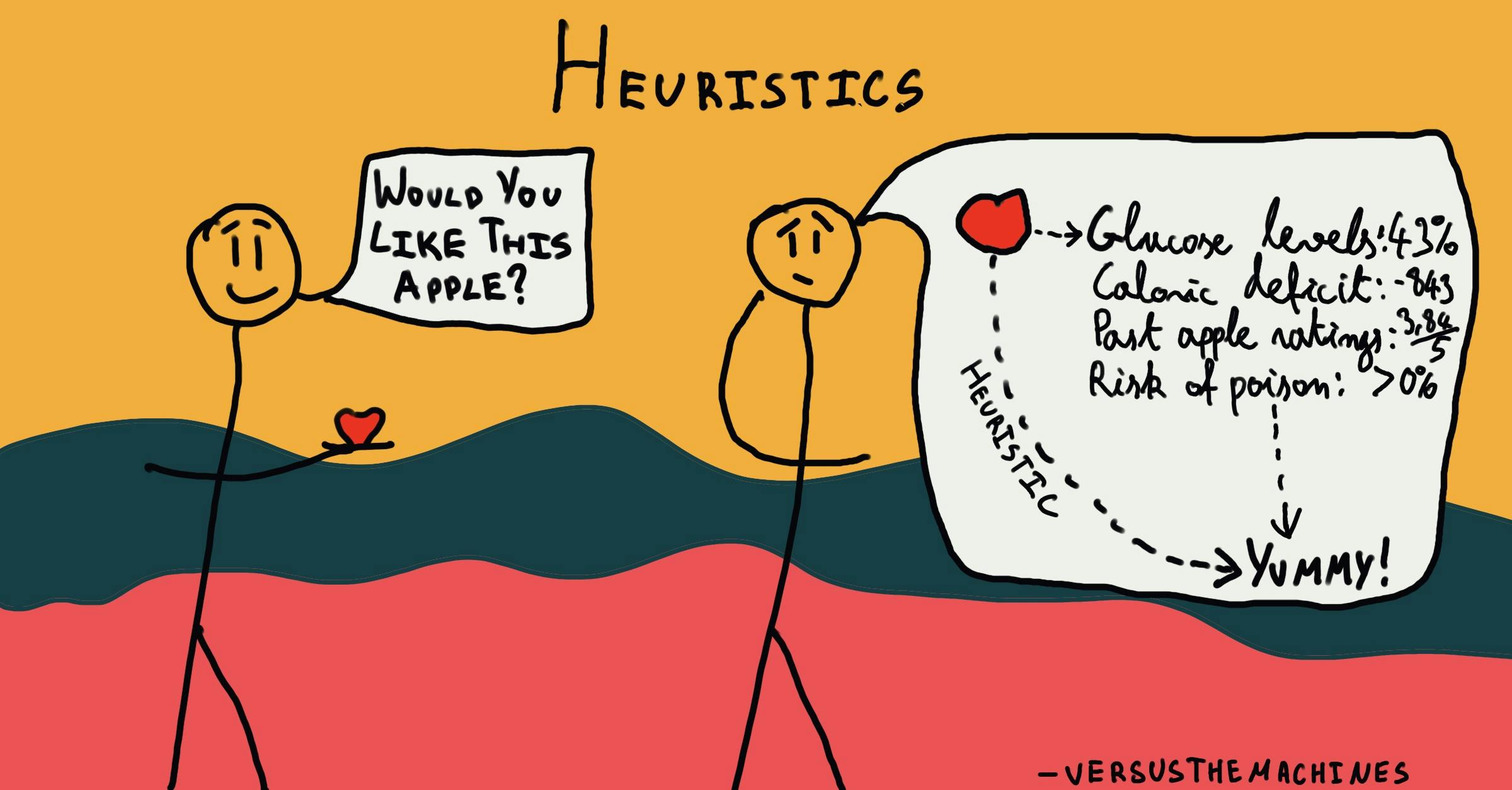

Heuristics

, explained.What are Heuristics?

Heuristics are mental shortcuts that can facilitate problem-solving and probability judgments. These strategies are generalizations, or rules-of-thumb, that reduce cognitive load. They can be effective for making immediate judgments, however, they often result in irrational or inaccurate conclusions.

Where this bias occurs

We use heuristics in all sorts of situations. For example, one type of heuristic, the availability heuristic, often happens when we’re attempting to judge the frequency with which a certain event occurs. Say someone asked you whether more tornadoes occur in Kansas or Nebraska. Most of us can quickly call to mind an example of a tornado in Kansas: the tornado that whisked Dorothy Gale off to Oz in Frank L. Baum’s The Wizard of Oz. Although it’s fictional, this example comes to us easily. On the other hand, most people have a lot of trouble calling to mind an example of a tornado in Nebraska. This leads us to believe tornadoes are more common in Kansas than in Nebraska. However, the two states report similar tornado activity.1

Heuristics don’t just pop up when we’re trying to predict probability. Simple heuristics show up across various domains of life, streamlining the brain’s decision-making process in the same way that keyboard shortcuts help us copy and paste text or switch between browser tabs. Like keyboard shortcuts we all know and love, heuristics are a problem-solving approach involving mental shortcuts that help us make decisions easier and faster.

Unfortunately, our cognitive time-savers are not always as accurate or reliable as the ones programmed into our computers. Just as the availability heuristic can cause us to judge the probability of a tornado in Nebraska inaccurately, heuristics often lead us to “good enough” conclusions that seem correct based on our previous experiences or pre-existing ideas but may not be objectively accurate. Why? Our brains often revert to heuristics when finding an optimal solution isn’t possible or practical—for example, you cannot evaluate every single restaurant in a big city before choosing a place to eat, so heuristics step in to help you make a decision that is likely to be satisfactory, even if it’s not optimal.