Why are we satisfied by “good enough?”

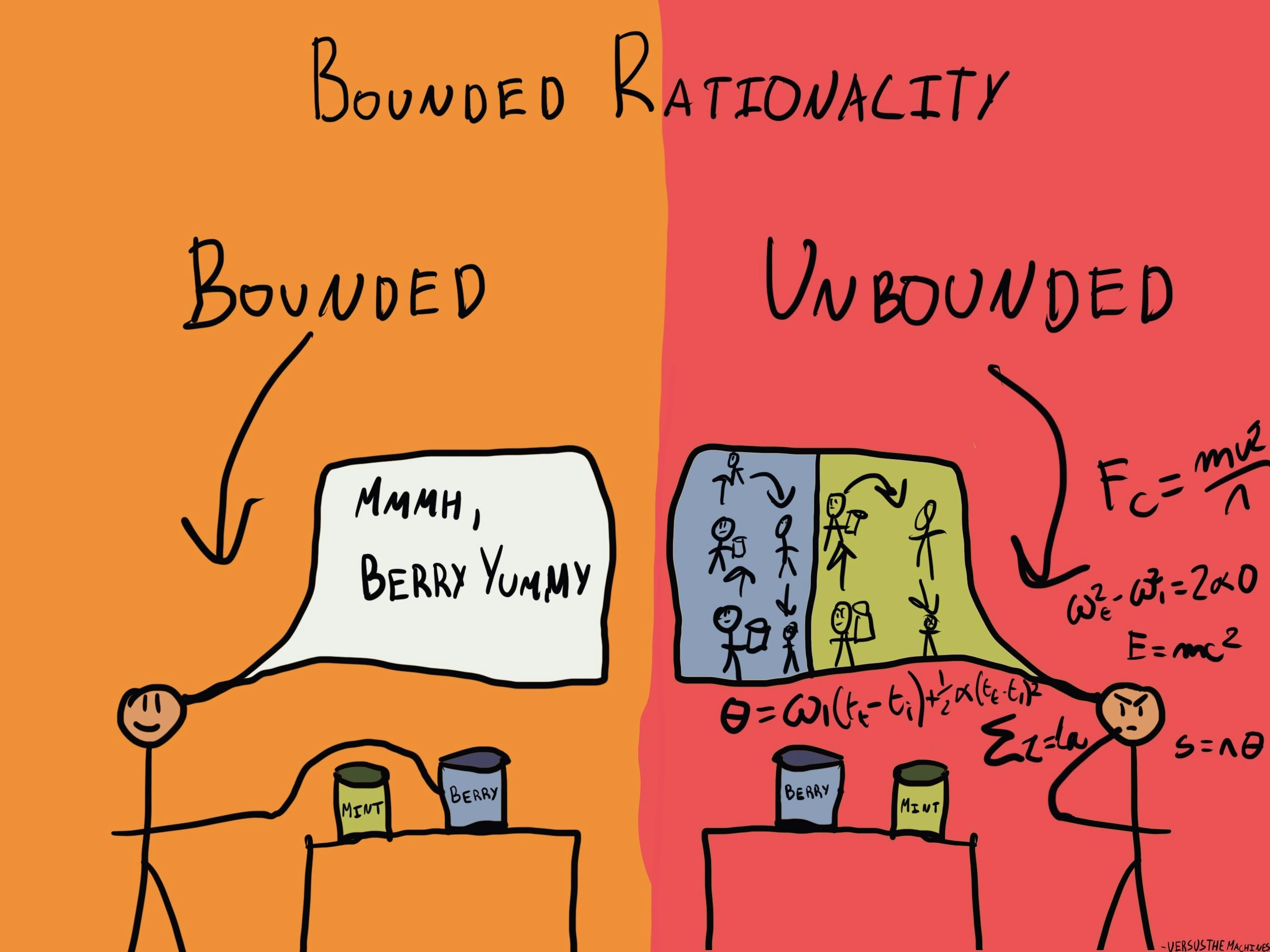

Bounded Rationality

, explained.What is bounded rationality?

Bounded rationality is a human decision-making process in which we attempt to satisfice rather than optimize due to limitations in our cognitive abilities. In other words, we seek a decision that is good enough rather than the best possible option, allowing us to make rational decisions within the bounds of our cognitive constraints.

Where this bias occurs

Imagine you are at the grocery store buying eggs. You look at the various brands and buy a carton of eggs labeled “cage-free.” This decision satisfies your desire to be ethical by choosing eggs from chickens not raised in cages.

However, when we make quick choices based on labels like “cage-free,” we often fail to stop and think about what those terms actually mean. Our decision is based on a false sense of rationality because we do not have all the information available. Maybe we don’t have the time to look up that “cage-free” can mean both “free-run” and “free-range,” but only “free-range” chickens have a chance to go outside.1 Bounded rationality encourages us to make decisions that satisfy a particular criterion, such as being ethical, without making the most optimal choice within that criterion.