Why do we compare everything to the first piece of information we received?

Anchoring Bias

, explained.What is the Anchoring bias?

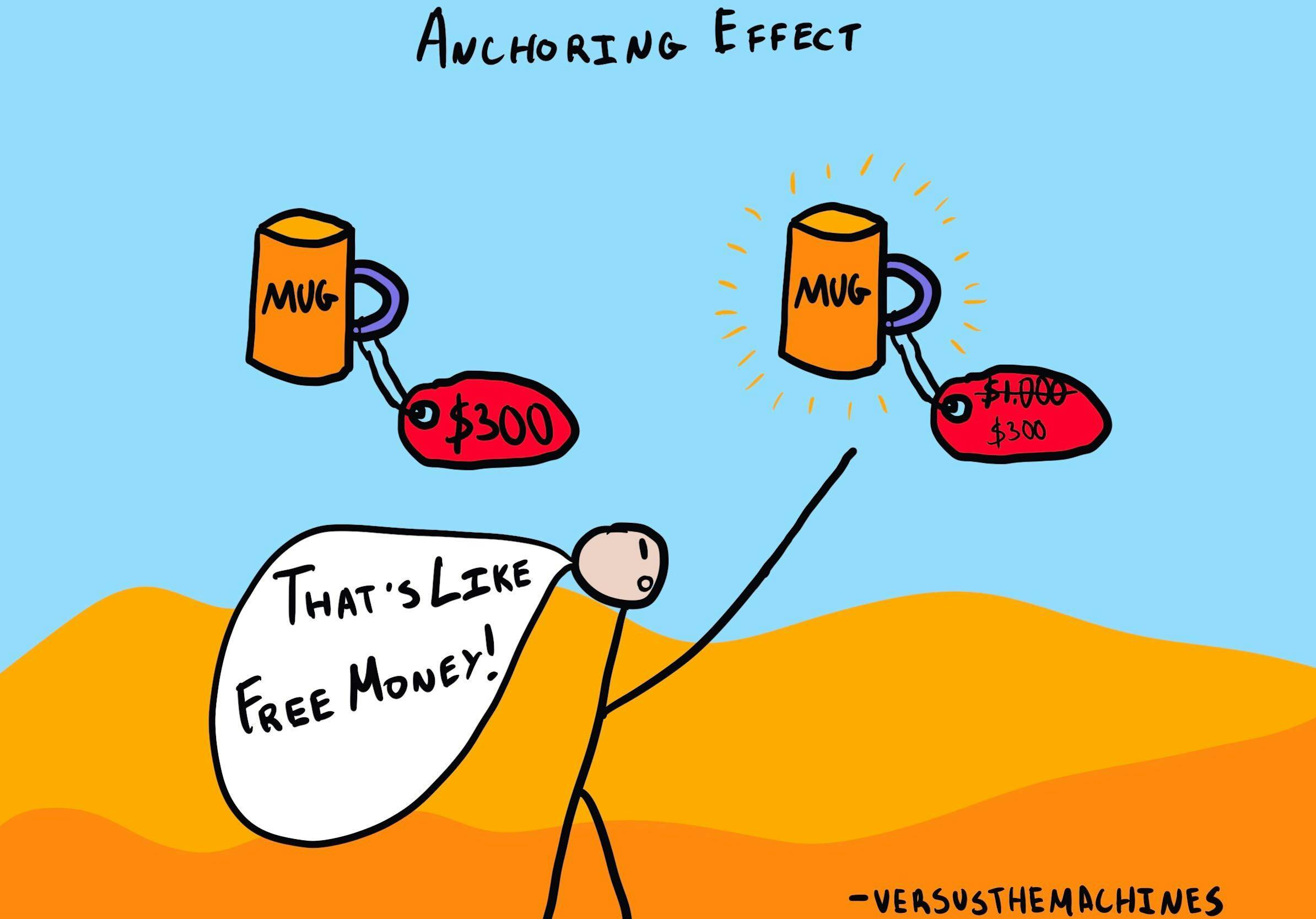

The anchoring bias is a cognitive bias that causes us to rely heavily on the first piece of information we are given about a topic. When we are setting plans or making estimates about something, we interpret newer information from the reference point of our anchor instead of seeing it objectively. This can skew our judgment and prevent us from updating our plans or predictions as much as we should.

Where this bias occurs

Imagine you’re out shopping for a present for a friend. You find a pair of earrings that you know they’d love, but they cost $100, way more than you budgeted for. After putting the expensive earrings back, you find a necklace for $75—still over your budget, but hey, it’s cheaper than the earrings! You buy them and make your way out of the mall.

As you’re leaving, you see a fun t-shirt hanging in a store window that your friend would really love, and it’s only $30. Why did you jump so quickly to buy the necklace instead of shopping around for other gift options? Because the initial price of the earrings became your anchor point for evaluating subsequent pricing information, shifting your perspective on what constitutes a good deal. The $100 established a clear price point in your mind. As a result, you evaluated the $75 necklace in relation to this set price point instead of looking at the cost objectively—the necklace seemed like a steal compared to the cost of the earrings! If you had encountered the necklace first, you would have been less inclined to buy it, instead holding out something in your budget like that awesome t-shirt.