Why do we prefer things that we are familiar with?

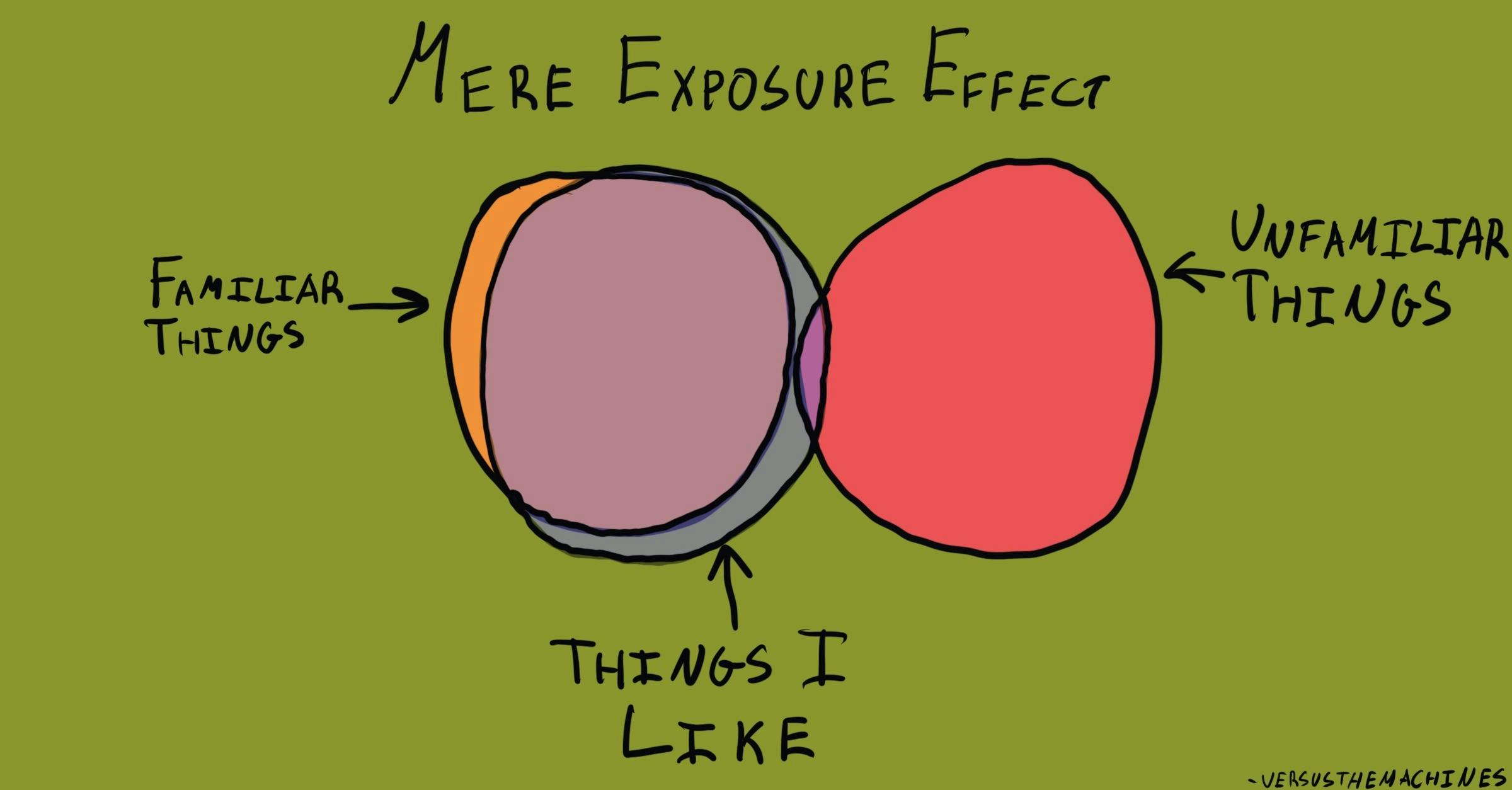

Mere Exposure Effect

, explained.What is the Mere Exposure Effect?

The mere exposure effect describes our tendency to develop preferences for things simply because we are familiar with them. For this reason, it is also known as the familiarity principle.

Where this bias occurs

Consider the following hypothetical situation: one day, Jane and her family visit an area called “Little Portugal” to eat lunch at a restaurant. Jane has never eaten Portuguese food before. As a result, when Jane looks at the menu, she doesn’t recognize any of the dishes; some of the ingredients are entirely foreign to her.

Jane doesn’t know what to order. Then, on the back side of the menu, she noticed that they also offer pizza and burgers. Finally, some familiar food! Jane loves pizza—she eats it all the time. So naturally, this is what she decides to order.

We prefer things we have been exposed to in the past, and our preference increases as our exposure does—a phenomenon known as the mere exposure effect. The more familiar something feels, the safer and more appealing it seems, which is why Jane instinctively gravitates toward pizza, even in a restaurant full of new and potentially exciting options.