The Paradox of Choice

What is the Paradox of Choice?

The paradox of choice is a concept introduced by psychologist Barry Schwartz which suggests that the more options we have, the less satisfied we feel with our decision. This phenomenon occurs because having too many choices requires more cognitive effort, leading to decision fatigue and increased regret over our choices.

The Basic Idea

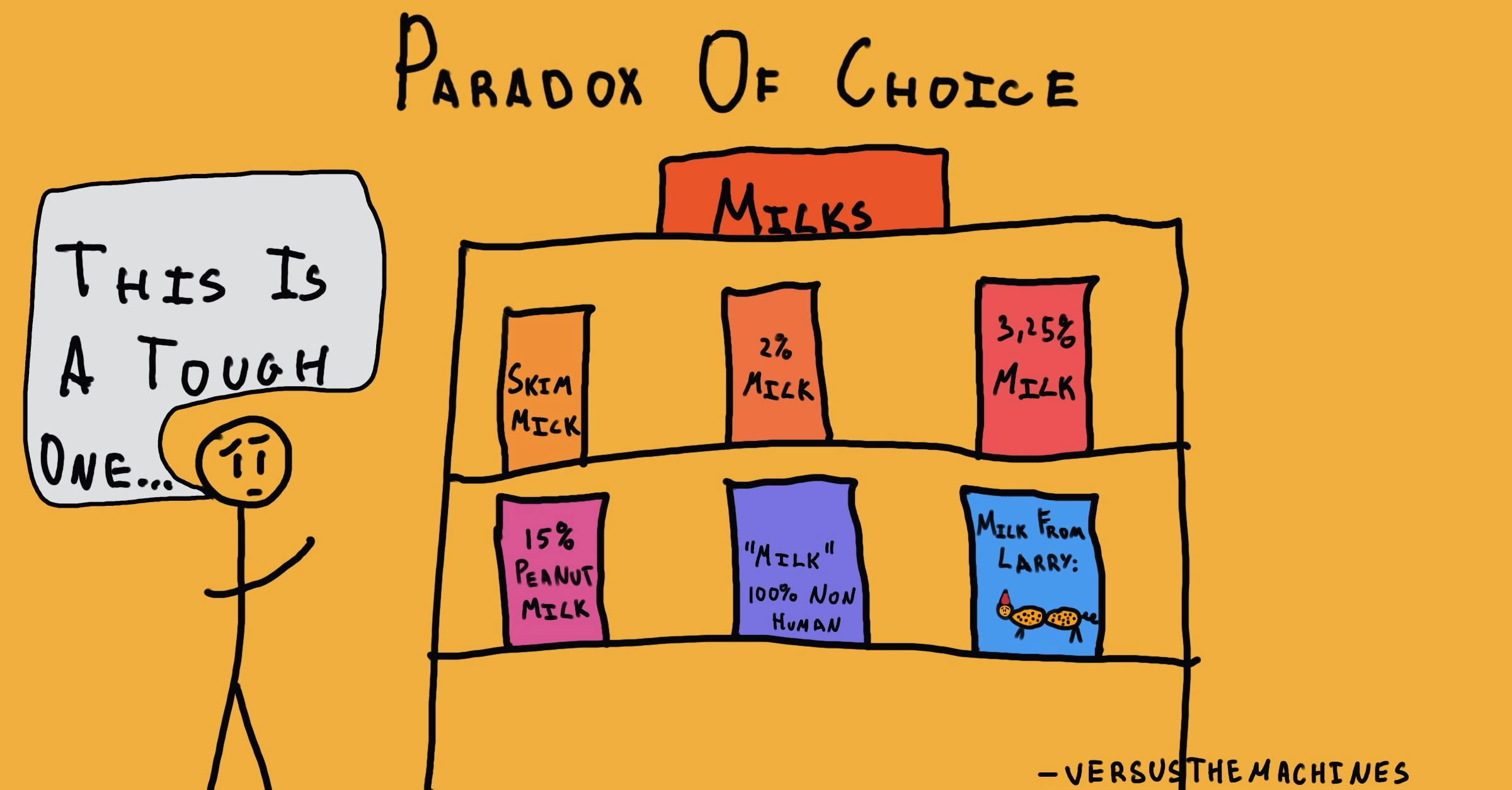

Imagine that you need milk, so you go to the grocery store to pick some up. When you get to the dairy aisle, you see that there are dozens of options. These days, not only do you have to make a decision on the percentage of fat you want (1%, 2%, skim, etc.), but also what source you want your milk to be coming from: cows, almonds, soybeans, oats…the list goes on. Almost dumbfounded, you stand in front of the aisle and have no idea what milk to pick. There are so many choices that you are overwhelmed.

This phenomenon is known as the paradox of choice, and it is becoming a concern in the modern world, where more and more options are becoming easily available to us. If we only had to choose between 1% and 2% milk, it would be easier to know which option we prefer since we can easily weigh the pros and cons. When the number of choices increases, so does the difficulty of knowing what is best. Instead of increasing our freedom to have what we want, the paradox of choice suggests that having too many choices actually limits our freedom.

Learning to choose is hard. Learning to choose well is harder. And learning to choose well in a world of unlimited possibilities is harder still, perhaps too hard.

– Barry Schwartz in his book The Paradox of Choice1

About the Authors

Dan Pilat

Dan is a Co-Founder and Managing Director at The Decision Lab. He is a bestselling author of Intention - a book he wrote with Wiley on the mindful application of behavioral science in organizations. Dan has a background in organizational decision making, with a BComm in Decision & Information Systems from McGill University. He has worked on enterprise-level behavioral architecture at TD Securities and BMO Capital Markets, where he advised management on the implementation of systems processing billions of dollars per week. Driven by an appetite for the latest in technology, Dan created a course on business intelligence and lectured at McGill University, and has applied behavioral science to topics such as augmented and virtual reality.

Dr. Sekoul Krastev

Dr. Sekoul Krastev is a decision scientist and Co-Founder of The Decision Lab, one of the world's leading behavioral science consultancies. His team works with large organizations—Fortune 500 companies, governments, foundations and supernationals—to apply behavioral science and decision theory for social good. He holds a PhD in neuroscience from McGill University and is currently a visiting scholar at NYU. His work has been featured in academic journals as well as in The New York Times, Forbes, and Bloomberg. He is also the author of Intention (Wiley, 2024), a bestselling book on the science of human agency. Before founding The Decision Lab, he worked at the Boston Consulting Group and Google.