Why do we buy insurance?

Loss-aversion

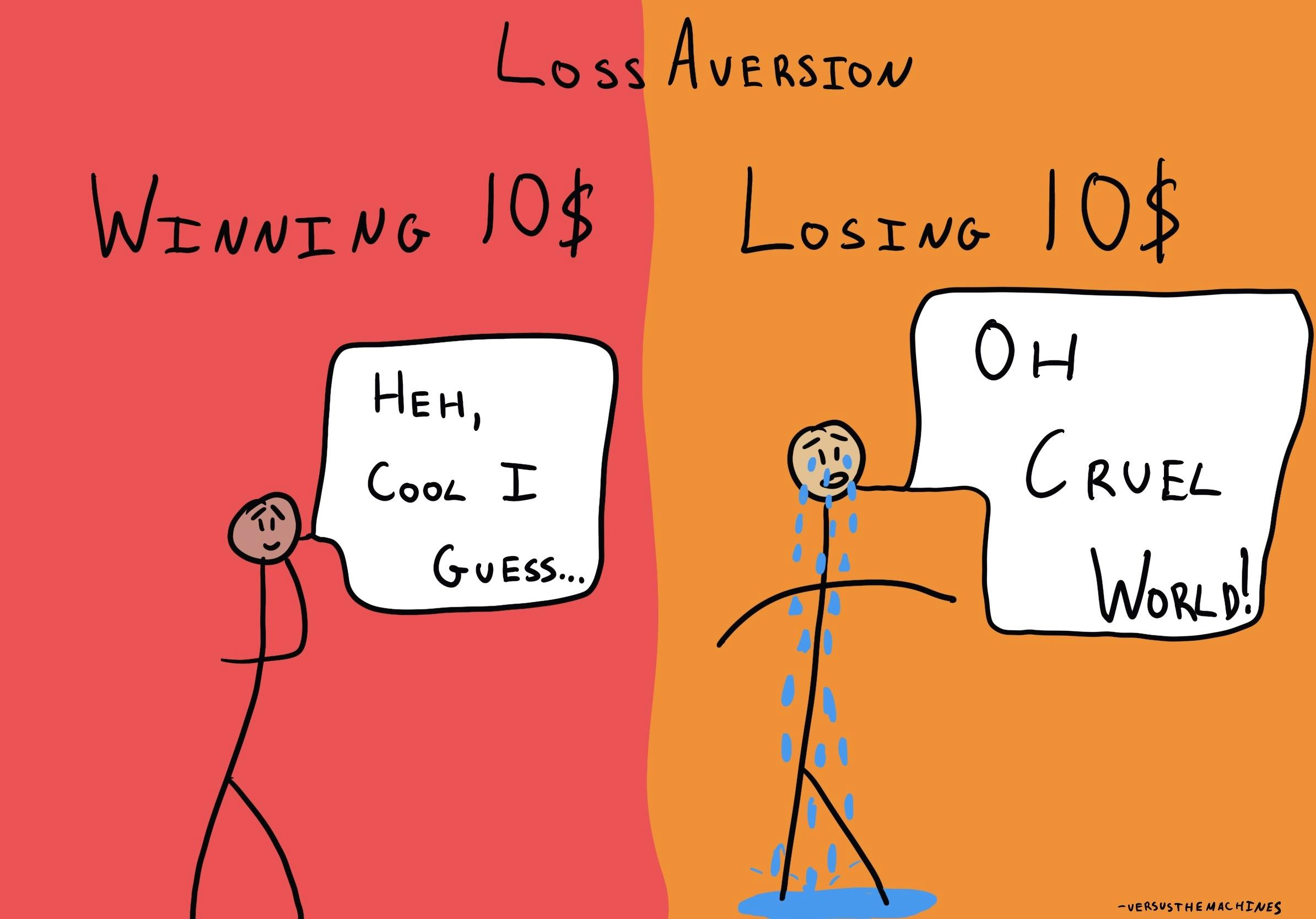

, explained.What is loss aversion?

Loss aversion is a cognitive bias that describes why, for individuals, the pain of losing is psychologically twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining. The loss felt from money, or any other valuable object, can feel worse than gaining that same thing.1 Loss aversion refers to an individual’s tendency to prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains. Simply put, it’s better not to lose $20, than to find $20.

Where this bias occurs

Loss aversion is a relevant concept in cognitive psychology, decision theory, and behavioral economics.

Loss aversion is especially common when we make financial decisions. An individual is less likely to buy a stock if there is a potential risk of losing money, even though the reward potential is high. Notably, loss aversion grows stronger as the stakes of a choice grow higher.2

Additionally, marketing campaigns such as trial periods and rebates exploit our tendency to opt into a presumed free service. Once a buyer incorporates a specific software or product into their lives, they are more likely to purchase it to avoid the loss they will feel once they give it up. This tends to happen because scaling back—whether on software trials, expensive cars, or bigger houses—is an emotionally challenging decision.

Debias Your Organization

Most of us work & live in environments that aren’t optimized for solid decision-making. We work with organizations of all kinds to identify sources of cognitive bias & develop tailored solutions.

Related Biases

Individual effects

Loss aversion can significantly impair our decision-making. As humans, we possess a natural tendency to avoid incurring loss. However, this fear can prevent us from taking even well-calculated risks with potential worthwhile returns.

Loss aversion is particularly pertinent to how we spend and manage our money. Financial decisions can have widespread impacts on many realms of our lives. This means that if we fail to make sound, calculated decisions with our finances, our choices can be detrimental.

Systemic effects

Loss aversion can prevent individuals, corporations, and countries from making risky decisions when addressing complex challenges. Though avoiding danger is important, this mentality might prevent us from implementing innovative solutions.

Before COVID-19, Brazil was already known worldwide for its ground-breaking tactics for solving pandemics. Compared to wealthier countries, Brazil faces unique constraints when attempting to contain outbreaks including poverty and insufficient funding.

That being said, Brazil had an ingenious solution to preventing the spread of mosquito-borne viruses, such as Zika, yellow fever, and dengue: genetic engineering. The same species of mosquitoes was modified to be all-male, not bite, and carry a self-destructive gene designed to kill them and all their progeny.3 This novel method was an extremely risky operation for Brazil to undertake that would have cost the country if it failed, but save millions of lives if it worked.

The project was a huge success, reducing mosquito larvae by 82% one year after the genetically modified mosquitoes were released and lowering the prevalence of dengue fever by 91%.4 If Brazil’s epidemiologists and politicians had possessed a higher level of loss aversion, they might have never taken on this initiative and discovered this unique solution to a global problem.

Oxitec, the company that provided Brazil with mosquito technology, found a solution that is both more effective and eco-friendly than other traditional methods such as insecticides. Unfortunately, more risk averse nations in Europe continue to lag in comparison to innovative nations like Brazil.4 Within the agriculture sector, Europe typically has a more conservative approach with outdated regulations. Even though these countries would greatly benefit from trying new and emerging technologies to address challenges with crop pests, their loss aversion encourages them to stick to the “safe” option instead: spraying pesticides.

How it affects product

As with any product, loss aversion impacts our inclination—or lack thereof—to purchase new digital devices. When your phone stops working, companies urge you to buy the newest model. However, the most recent model often means the most expensive model, making us hesitate before immediately making the purchase.

Loss aversion may encourage you to settle for the same model as before to avoid spending any more than necessary. In fact, some of us may even be tempted to buy a refurbished model to spend the least amount possible. However, this option will only save you money in the short term. Before you know it, this used phone will die, bringing you back to square one.

In this case, technology companies might be right. Brand new devices can be more worthwhile than older ones, despite what our loss aversion might tell us.

Loss aversion and AI

AI can help nudge us toward making better decisions. When we approach a dilemma, we evaluate our options with a tendency to overestimate losses and underestimate gains. Meanwhile, machine learning algorithms always approach dilemmas in the same way: making predictions based on fine-tuned statistical patterns. This formula grants gains and losses equivalent weights, allowing the software to accurately calculate our net benefit from following through with a choice.15 Of course, this doesn’t mean we should rely on ChatGPT for dictating every decision we make, but it can be a useful tool when we feel loss aversion clouding our judgments.

Why it happens

Loss aversion results from three coinciding components: our neurological makeup, socioeconomic factors, and cultural background.

Our brains

Three specific brain regions become activated in situations involving loss aversion.

The amygdala is the part of our brain that primarily processes fear, creating an automated, pre-conscious sense of anxiety when we detect danger. Loss aversion also activates the amygdala, which explains why our visceral reaction to danger, such as seeing a spider or snake, is so similar to our visceral reaction to loss, such as losing money or possessions. Both situations stimulate the release of hormones like adrenaline and cortisol, energizing us to protect ourselves and avoid getting hurt. This overlap explains why loss aversion is so hard to resist: our brains and bodies are automatically programmed to be scared of loss!5

The second brain region engaged by loss aversion is the striatum, which is responsible for calculating prediction errors and anticipating events. Although the striatum shows increased activity when we experience both losses and their equivalent gains, it lights up even more for losses.6 This unbalanced reaction suggests that the striatum helps us avoid losses rather than motivating us to seek gains.

Finally, our brain’s insula area reacts to disgust, working with the amygdala to encourage us to avoid certain types of behavior. Neuroscientists have noted that the insula region also lights up when responding to a loss. The higher the prospect of loss, the more activated the insula becomes compared to an equivalent gain, potentially explaining why we are so repulsed by losing out.7

Though there are many other parts of the brain that contribute, these three regions are vital to understanding how we process and respond to loss. The strength of these regions in each person may determine how loss averse they are.5

Socio-economic factors

Socio-economic factors also play an essential role in one’s individual disposition to loss aversion, such as their placement within the social hierarchy. Ena Inesi, an Associate Professor of Organizational Behavior at the London School of Economics, found that powerful people are less loss averse because their status and network places them in a privileged position to handle a loss if it should incur.8 As a result, these individuals give less weight to losing out than the average person since it is a less risky endeavor for them. To no surprise, Inesi’s research also suggests that powerful individuals value gains more than others, further explaining why they are success driven rather than failure deterred.8

Wealth also plays an important role in our inclination toward loss aversion. Like powerful people, wealthy people typically have an easier time accepting losses they incur due to additional financial resources. But interestingly enough, their level of loss aversion may be modified by how wealthy their social environment is as well.

One study in Vietnam revealed that wealthier villages were overall less loss averse than poor villages. Those with higher mean incomes situated in affluent areas were more willing to take risks in particular.8 However, wealthy individuals who lived in poor environments were more likely to fear losing out than poor individuals who lived in wealthy environments.9 These findings suggest that our level of loss aversion may be just as determined by the financial well-being of the people surrounding us as our own. In short, a complex combination of personal and environmental socioeconomic traits determines our willingness to take risks when making decisions.

Culture

Cultural background has been linked to how loss averse an individual may be. A study conducted by Mei Wang surveyed groups from 53 different countries to understand how different cultural values affect one’s perception of losses compared to gains. The group discovered that people from Eastern European countries tended to be the most loss averse, with people from African countries being the least.10

One explanation for this variation among cultures lies in the difference between collectivist and individualist cultures. Those from collectivist cultures who value closer social connections may be less loss averse because they can rely on their friends, family, and community if they make a poor decision.11 This support system helps individuals take risks without feeling losses as intensely. On the other hand, those from individualistic cultures that do not value close relationships lack the same social safety net as their collectivist counterparts.

Why it is important

Many of the most important decisions an individual will face will require incurring losses in hopes of potential gains. Although avoiding risks can be useful in many situations, it can discourage people from logically evaluating situations when the fear of losing out is too intense. Loss aversion prevents people from making the best decisions possible to avoid failure. In reality, the real failure may be missing out on opportunities such as accepting a new job offer or buying a new house that could improve one’s overall well-being, even at the expense of a temporary loss.

How to avoid it

Loss aversion is a natural human tendency that exists to keep us from incurring losses. That being said, it is essential to know how to avoid loss aversion to prevent it from influencing our decisions, especially when there are potential gains to be made. There are two main strategies we can use to fight back against this bias: framing and putting loss into perspective.

Framing

The way that a transaction is framed can significantly influence an individual’s perception of loss aversion. Phrasing a question as a loss may increase loss aversion, while phrasing that same question as a gain may reduce loss aversion, leading to a more calculated response.12 When proposing a transaction, try framing the options in a way that highlights the potential benefits that can be achieved, rather than emphasizing the risks.

Putting Loss into Perspective

A simple way to tackle loss aversion is to ask ourselves what the worst outcome would be if the course of action was taken. Usually, this helps us put loss and the strong associated feelings with it into perspective. This way, we can get over our fears and better rationalize if it is worth making a decision or not.

How it all started

Loss aversion was first identified and studied by cognitive mathematical psychologist Amos Tversky and his associate Daniel Kahneman.1 Although they first coined the term in 1979 in a landmark paper on subjective probability, it was more notably described in 1992 when outlining a critical idea behind this bias: people react differently to negative and positive changes. More specifically, Tversky and Kahneman’s research demonstrated that losses are twice as powerful compared to their equivalent gains, a foundational concept of prospect theory.13

Prospect theory describes how individuals decide between and estimate the perceived likelihood of different options. For example, individuals might agree to pay for a likely smaller cost instead of a potentially greater but much less likely cost. This decision is due to loss aversion encouraging an individual to avoid taking any financial risks.

Example 1 – Insurance

Loss aversion is commonly used by organizations when trying to sell their products. This is seen with insurance companies whose business models rely on individuals’ need for security and their desire to avoid losses and risks. On insurance websites, there is typically a long list of unlikely and costly outcomes that individuals may encounter if not properly insured.14 Reading these unfortunate events prime us towards recognizing losses and trying to avoid them by purchasing insurance.

Additionally, these large insurers want customers to focus on significant and looming potential losses while forgetting the small but constant payments they would need to commit to get insurance coverage. Loss aversion can explain the need to commit to insurance plans, even if the losses outlined in the plans are unlikely to occur.

Example 2 – Taking financial risks

Examples of loss aversion are particularly notable when looking at financial decision-making. Based on this cognitive bias, it can be assumed that an individual will more heavily weigh potential costs and failures than potential benefits and rewards, especially when it comes to managing their own money.

When making investments, an individual typically focuses on the associated risk rather than the potential gains. A common philosophy among stock traders is that once you have sold a stock, you should refrain from checking up on it. This is often said because many individuals become hyper-focused on investments that lose money while ignoring investments that make money.

Furthermore, this obsession with preventing loss can be seen when an individual is deciding whether to sell their house below the value they purchased it. Even though selling at that moment may be the best option and the largest amount of money an individual will receive for their purchase, people may be unwilling to make that financial decision as they perceive it as an overall loss.

Another example of loss aversion concerning financial decisions can be observed in the price sensitivity of people buying groceries. Daniel Putler’s study on behavioral economics looked at the correlation between the price of eggs and demand change. Between July 1981 and July 1983, Putler’s team noted that when there was a 10% increase in the price of eggs, the demand for eggs, in turn, dropped 7.8%. In contrast, when there was a 10% decrease in the price of eggs, the rise in demand was only 3.3%. This study exemplifies price sensitivity in response to loss aversion, with individuals influenced by additional spending more than potential savings.14

Summary

What it is

Loss aversion is a cognitive bias that explains why individuals feel the pain of loss twice as intensively as the equivalent pleasure of gain. As a result of this, individuals tend to try to avoid losses in whatever way possible.

Why it happens

Loss aversion is an innate cognitive bias resulting from many factors including neurological makeup, socioeconomic status, and cultural background.

Example 1 – Insurance companies use loss aversion as a business model

Insurance companies try to attract new customers by demonstrating the many potential and costly losses just one person can incur in a lifetime. To avoid these risks, an individual would rather pay a small and consistent fee, as seen in most insurance companies’ business models.

Example 2 – Why loss aversion prevents us from taking financial risks

Loss aversion is common in many instances of financial decision-making. When making investment decisions, selling assets, or purchasing groceries, loss aversion influences individuals and their fear of losing money.

How to avoid it

Loss aversion can be avoided by both stressing potential gains and identifying worst-case scenarios to better evaluate our available options.

Related TDL articles

How Loss Aversion Affects Our Perceptions of Weight

In this article, Kaylee Somerville introduces a new phenomenon known as weight gain aversion. Just as we react more strongly to losing money than earning it, we also react more strongly to putting on weight than losing it, no matter how we felt about our original weight. Somerville exposes how aversion causes many common weight loss tactics like daily weigh-ins to fail and proposes healthier alternatives to counteract this bias and meet our fitness goals.

Loss Aversion and Carbon Pricing

This article outlines the role of loss aversion in impacting consumer attitudes and responses toward carbon pricing policies. Many experiments have found that phrasing consumer tax reimbursements as an incentive increased positive feelings toward these regulations.