Why do we lose interest in an activity after we are rewarded for it?

Overjustification Effect

, explained.What is the Overjustification Effect?

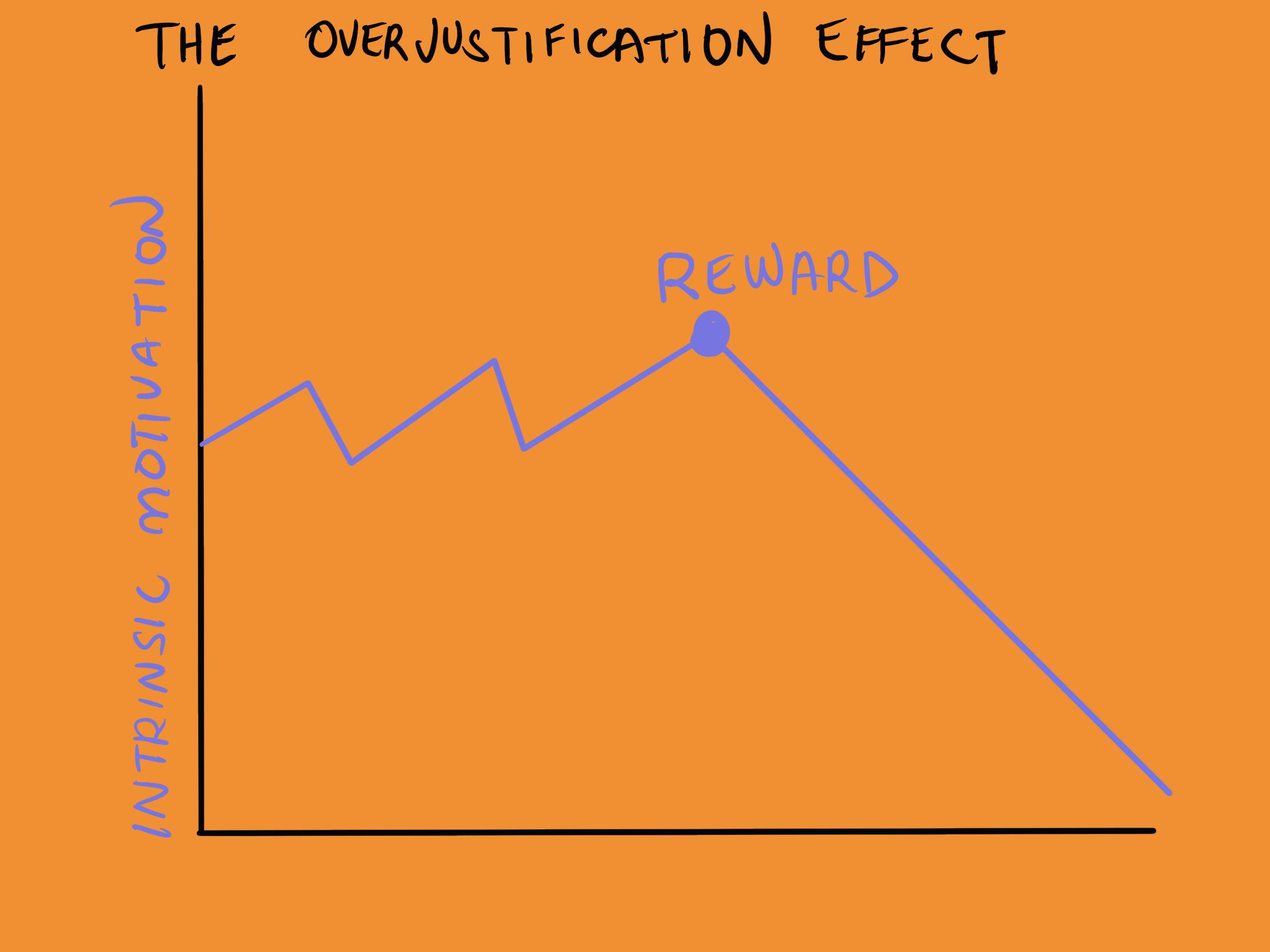

The overjustification effect describes our tendency to become less intrinsically motivated to partake in an activity that we used to enjoy when offered an external incentive such as money or a reward.

Where this bias occurs

The overjustification effect can occur for any activity that we find intrinsically valuable. We do these activities because we enjoy them, not because they are a means to achieve an external goal or reward.1

For example, imagine that you have always loved painting because you find the activity calming. You start giving out paintings to friends and family as gifts, and a number of them suggest that you start selling them on Etsy. Thinking it might not be such a bad idea to make extra money, especially for an activity you love, you set up a page and charge people $20 for a painting. A while after you start painting to fulfill orders, painting no longer feels enjoyable. It feels like a chore.

You have lost the intrinsic motivation to paint since you were offered money for an activity you love. Your intrinsic motivation to paint has been replaced with extrinsic motivation, which is motivation created by an external reward, such as money.2 However, replacing your intrinsic motivation for money has actually caused you to feel less motivated to paint. Even if you stop selling, your intrinsic motivation may not fully return, as you now attribute your past enjoyment to external rewards rather than personal satisfaction. Now, your external justifications for painting have overshadowed your inherent enjoyment of the activity itself. This is known as the overjustification effect.