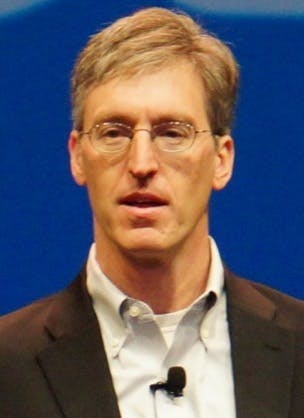

Steven Levitt

Incentives are Everything

Intro

Steven Levitt is an economist, innovative thinker, TED-talk speaker, best-selling author, and above all, a brave thinker whose interest in the real world has helped revolutionize the application of economics for over a decade. By discovering links between unique disciplines, Levitt has been able to take economic theory beyond textbook pages and explore the ways economics interacts with psychology, sociology and behavioral science.

At the top of Steven Levitt’s impressive resume is his best-selling book, Freakonomics, published in 2005. Freakonomics is not just a book - it is a way of thinking that has inspired subsequent books and an empire. Thanks to Levitt’s thinking outside-the-box approach, his work has been influential in a number of fields: the social sciences, political sciences, the economics of crime and the study of law.1

Economics is about going into the world and finding puzzles and thinking about how understanding incentives of markets might help us get a better grasp of what’s really going on.

- Steven Levitt on the EconTalk podcast.2

On their shoulders

For millennia, great thinkers and scholars have been working to understand the quirks of the human mind. Today, we’re privileged to put their insights to work, helping organizations to reduce bias and create better outcomes.

Economic Impact of Abortion

Known for stringing together seemingly separate fields, some of Levitt’s most notable (and controversial) work has revolved around crime. Traditional economists have long held onto the belief that when nations perform well economically, crime decreases. Data has shown, however, that this is not the case.3 There must be other factors influencing the level of crime outside economic theory.

With this in mind, Levitt has explored how various factors impact the level of crime, with one factor being abortion. In his paper “The Impact of Legalized Abortion on Crime,” Levitt recognized that in the 1990’s, the United States experienced one of the greatest drops in homicide rates, violent crimes and property crimes. Although some explanations were put forward (increased rate of incarceration, improved police procedures, a strong economy), none of these fully explained the drop.3 Instead, Levitt and his colleague John Donohue proposed a novel explanation: that the Supreme Court’s decision to legalize abortion in 1973 in Roe vs Wade was the reason the U.S was experiencing a drop in crime levels.3

Levitt and Donohue examined the legalization of abortion through an economic lens to help describe why it might affect crime rates. For one, they proposed that the large-scale legalized abortion that occurred immediately following the decision led to decreased births in the years following. Because there were fewer people, particularly males, born in the years after 1973, there were less adult men alive in the 1990’s to commit crimes.3

Another socio-economic explanation was that the women who have abortions are often teenagers, unmarried, and frequently below the poverty line. Unfortunately, these demographics are at greater risk of giving birth to children who would commit crimes. Since these women were able to take advantage of legalized abortion (and data showed that they were the group most likely to), there would be a fewer number of individuals in the population prone to committing crime.3

Being careful not to give an ethical perspective on the situation, Levitt and Donohue write that “in attempting to identify a link between legalized abortion and crime, we do not mean to suggest that such a link is ‘good’ or ‘just,’ but rather, merely to show that such a relationship exists.” (382).3

The link between legalized abortion and crime is just one example of the causal relationships that Levitt was interested in. As a researcher, Levitt frequently applied empirical analysis to data that enabled him to help solve puzzles that had long confounded people,1 such as why crime was dropping at such high rates in the 1990’s.

Casting Doubt on the Median Voter Theorem

Levitt also conducted a great deal of research into the field of politics. Levitt used his empirical strategy to dispel the widely-held principle that, based on traditional economic principles, greater campaign spending would yield positive voter results. In his 1994 paper, “Using Repeat Challengers to Estimate the Effect of Campaign Spending on Election Outcomes in the U.S. House,” Levitt suggested that campaign spending actually had very little impact on election outcomes.4

In a subsequent 1996 paper, “How Do Senators Vote? Disentangling the Role of Voter Preferences, Party Affiliation, and Senator Ideology,” Levitt also cast some doubt on the median voter theorem.5 The median voter theorem suggested that a “majority rule voting system will select the outcome most preferred by the median voter.”6 This theory is based on an assumption that people will vote for the party whose views most closely align with their own ideologies, which means that parties are fighting to secure those median voters who fall somewhere near the middle of the political spectrum.7 In theory, that would also mean that senators vote on bills to appease the median voter. However, there are other factors at play: pressure from other party leaders in Congress and a senator’s own ideological stance. Levitt suggested that these additional pressures, while not usually observable, might displace the median voter theorem.5 While the median voter theorem might reflect a simplistic understanding of the relationship between the wishes of the overall electorate and the way a senator votes, Levitt wanted to more deeply understand the complexities of this relationship.

In the paper, Levitt concludes that the largest factor influencing the way a senator votes on bills and policies is their own ideologies.5 He suggests that the reason we observe senators from the same state or party tending to vote in similar ways is not because they are attempting to appease the overall electorate, but because they are usually drawn from a pool of candidates with similar political views.5

Incentives are the “cornerstone to the modern world”

One of the biggest arguments of Superfreakonomics, the sequel to Levitt’s first book, is the importance of incentives on human behavior. In the book, Levitt outlines case studies of the ways teachers, realtors, drug dealers and pregnant women have all behaved in response to the unintended consequences of incentives.8 His book, alongside the rest of his work, aims to show these hidden parts of economic theory.

Levitt’s original book outlines three different kinds of incentives: economic incentives, social incentives, and moral incentives. Levitt suggests that all of human behavior, as well as any change in the economic world, can be explained by one or more of these incentives.9

Levitt’s theory still incorporates economic incentives as a motivator of human behavior, however, unlike in traditional economic theory, he does not suggest that all decisions are made based on what will benefit an individual economically. Levitt shows that there are other powerful influences on what is thought to be the ‘best’ choice, namely a desire to do the right thing or a desire to be accepted by others.

In Superfreakonomics, Levitt also looks at reasons why particular incentives do or do not work. He suggests that incentives need to provide simple, actionable solutions in order to be effective.10 He uses the example of the seatbelt as a simple solution to helping reduce car crash fatalities - since there were few disincentives, people were likely to use the seatbelt.10 The fact that climate change, on the other hand, does not offer a simple solution suggests that people don’t feel incentivized to make a change.

Levitt’s work expands the concept of incentives from a purely economic stance to a moral stance, allowing him to more closely examine the ways humans actually behave.

Historical Background

Steven Levitt was born May 29th, 1967, in Minneapolis.1 He attended the prestigious private St. Paul Academy and Summit School, setting him up for great academic success from a young age. He stayed close for college, attending Harvard, where he graduated with a B.A. in Economics in 1989.11 He began working for a Fortune 500 company after graduating, as a consultant, before returning to school. He continued his education at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and received his PhD in Economics in 1994.11

In 1997, Levitt joined the University of Chicago faculty as a professor in Economics, a post he still affiliated with today. Today, he is the William B. Ogden Distinguished Service Professor and Director of Becker Center for Price Theory at the University of Chicago.12 As he began publishing papers about crime and economics back in the 1990’s, Levitt started making a real name for himself. He was awarded the John Bates Clark Medal in 2003, an award granted by the American Economic Association to a significant economist under the age of 40.13

It wasn’t until 2005 that Steven Levitt really became a house-hold name. In 2005, alongside journalist Stephen Dubner, Levitt co-authored Freakonomics, a book made up of a number of case studies. It all began when Dubner visited Chicago to shadow Levitt for The New York Times. Although Levitt was originally hesitant, after the Times article came out, a partnership was formed.14 Levitt and Dubner didn’t expect much to come from their book, but it went on to sell over 5 million copies and be translated into 40 different languages.14 That didn’t mean that it was without controversy - its status as an economic book was constantly questioned. Some people claimed it lacked economic substance and should be considered a sociology book because at times, its claims were speculative. Harsher criticism has suggested that the book is a form of academic imperialism that attempts to apply an economic perspective to a number of unrelated fields.15

Despite the criticism Freakonomics faced, Steven Levitt was named one of Time Magazine’s “100 People Who Shape Our World” in 2006.11 Levitt and Dubner also went on to write three sequels, create a documentary, start a blog and produce a radio show.14 The two are now known as a package deal and continue to work together to grow their Freakonomics empire.

Steven Levitt Quotes

“Most of us want to fix or change the world in some fashion. But to change the world, you first have to understand it.”

- Levitt in Superfreakonomics

Steven Levitt did not want to dismiss economic theory, or sociological theories, but help combine them instead. He suggested that “morality, it could be argued, represents the way that people would like the world to work, whereas economics represents how it actually does work.” 18

But, Levitt knew that economics needed to get away from the books and theory and move towards empirical observation. He said that “the conventional wisdom is often wrong,” and that we should not “listen to what people say; watch what they do.”18

One of his strongest convictions is the role that incentives play in driving human behavior. He claimed that “an incentive is a bullet, a key: an often tiny object with astonishing power to change a situation.”18

Levitt has dedicated himself to his work, and emphasizes the need to love what you do. He said, “why is it so important to have fun? Because if you love your work (or your activism or your family time), then you’ll want to do more of it. You’ll think about it before you go to sleep and as soon as you wake up; your mind is always in gear. When you’re that engaged, you'll run circles around other people even if they are more naturally talented.” 18

Published Works

Freakonomics - The Series

In the first book of the sequel, Freakonomics, Levitt and Donohue begin their work by looking at vast amounts of collected data and asking simple questions. For example, imagine you are asked whether a gun or a swimming pool is more likely to kill someone. Your knee-jerk reaction is likely to be the gun, but in this book, Levitt and Donohue reveal the reality that a swimming pool is much more likely to kill someone.

In the first sequel, Superfreakonomics, Levitt and Donohue continue their simple-question approach, adhering to their story-telling style . Some of the most taboo topics this sequel takes on have to do with sex: why does the demand for sex increase on holidays? Why has the price of oral sex diminished? How has the sex trade enjoyed relatively stable high prices? 10

The third book of the series, Think Like a Freak, can be understood as a blueprint that guides people how to think outside-the-box and begin to solve problems using the same methods employed by Levitt and Donohue.

In what currently stands as the last book of the series, When to Rob a Bank, which came out 10 years after Freakonomics was first published, Levitt and Donohue have compiled some of the best posts from their blog. The book is less formal than the first three in the series and offers up an easier way to sink your teeth into the Freakonomics world.

TED Talks

Steven Levitt has also given a couple of TED talks. His first, “The freakonomics of crack dealing,” examines data on the financial situation of drug dealing. In his second talk, “Surprising stats about child car seats”, Levitt suggests that car seats are only as effective as seatbelts when it comes to saving children’s lives in car crashes.

Published Papers

Steven Levitt also has a whole host of published papers. His first, in 1994, questioned the belief that campaign spending was equated to greater voting outcomes. His latest paper, published in 2020, is entitled “Introducing CogX: A New Preschool Education Program Combining Parent and Child Interventions.” In this recently published paper, Levitt proposes the best way to design effective early childhood interventions.

Podcasts

Levitt and Donohue’s website is also home to their podcast, Freakonomics, which covers a range of economic issues. Some of the most recent episodes dive into the psychology and economics behind advertising, however the pair also take on heavier topics such as institutional racism.

You can also check out this EconTalk’s episode featuring Steven Levitt. In this podcast episode, Levitt provides insight into his surprise over Freakonomics’ success, as well as all the controversy it sparked.

References

- Bondarenko, P. (n.d.). Steven D. Levitt. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved December 21, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Steven-Levitt

- EconTalk. (2020, November 9). Steven Levitt on Freakonomics and the State of Economics. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/steven-levitt-on-freakonomics-and-the-state-of-economics/id135066958?i=1000497770279

- Donohue, J., & Levitt, S. (2001). The Impact of Legalized Abortion on Crime. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(2), 379-420. https://doi.org/10.3386/w8004

- Levitt, S. D. (1994). Using repeat challengers to estimate the effect of campaign spending on election outcomes in the U.S. house. Journal of Political Economy, 102(4), 777-798. https://doi.org/10.1086/261954

- Levitt, S. D. (1996). How Do Senators Vote? Disentangling the Role of Voter Preferences, Party Affiliation, and Senator Ideology. The American Economic Review, 86(3), 424-441. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/2118205

- Henderson, D. (2018, April 5). The Power of the Median Voter Theorem. Econlib. https://www.econlib.org/archives/2017/10/the_power_of_th.html

- Eezelaya. (2009, May 21). Median Voter Theorem Animation [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cFt0k6n_HKc

- Vitasek, K. (2011, January 9). Steven D. Levitt: It’s all about incentives. Future of Sourcing. https://futureofsourcing.com/steven-d-levitt-it-all-about-incentives

- LitCharts. (n.d.). Incentives: Theme Analysis. Retrieved December 21, 2020, from https://www.litcharts.com/lit/freakonomics/themes/incentives

- Brand Genetics. (2014, June 16). Superfreakonomics [Speed summary]. https://brandgenetics.com/superfreakonomics-speed-summary/

- GradeSaver. (2020, May 5). Freakonomics Study Guide. https://www.gradesaver.com/freakonomics

- University of Chicago News. (2011, April 10). Steven Levitt. https://news.uchicago.edu/profile/steven-levitt

- Course Hero. (n.d.). Steven D. Levitt & Stephen J. Dubner Biography. Retrieved December 21, 2020, from https://www.coursehero.com/lit/Freakonomics/author/

- Freakonomics. (n.d.). About. Retrieved December 21, 2020, from https://freakonomics.com/about/

- Course Hero. (n.d). Freakonomics: 10 Things You Didn’t Know. Retrieved December 21, 2020, from https://www.coursehero.com/lit/Freakonomics/things-you-didnt-know/

- Levitt, S. D. (2006, March 8). My wife Jeannette gets her props. Freakonomics. https://freakonomics.com/2006/03/08/my-wife-jeannette-gets-her-props/

- Kompanek, C. (2014, May 9). ‘Freakonomics’ Co-author Steven Levitt talks data – and dieting. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/1b96cfdc-d13b-11e3-9f90-00144feabdc0

- Goodreads. (n.d.). Steven D. Levitt Quotes. Retrieved December 21, 2020, from https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/798.Steven_D_Levitt

About the Author

The Decision Lab

The Decision Lab is a Canadian think-tank dedicated to democratizing behavioral science through research and analysis. We apply behavioral science to create social good in the public and private sectors.