Can We Afford to be Time Poor? The Hidden Tax of Time Poverty

We are all familiar with the constant struggle to manage money. But what if there was another resource, just as valuable, that follows the same rules? You can spend it, save it, waste it, invest it, or even give it away. The twist? It's not in your wallet.

This elusive resource isn't a new cryptocurrency or a hidden stash of diamonds. It's time. We constantly juggle it like a budget—but, unlike money, there's no ATM for more hours. This pervasive feeling of having too much to do and not enough time to do it is what researchers call time poverty. This deficit of leisure extends beyond mere busyness; it is a sneaky tax on our well-being that's often overlooked in the pursuit of productivity.

From physical to mental health, the impacts of being chronically time-starved are profound and far-reaching. In this article, we'll explore the hidden costs of time poverty, why it should matter to individuals and organizations alike, and how rethinking our relationship with time could be as significant as seeking financial assistance.

But first… what exactly is time poverty?

The concept of time poverty isn't new. Back in 1977, economist Clair Brown brought attention to a critical oversight in traditional poverty metrics which focused solely on income.1 She argued that these metrics failed to account for the unpaid labor required to run a household—activities like cooking, cleaning, and childcare. This oversight means that our current systems only account for material poverty, not time.

Imagine a single parent juggling two jobs. They might be able to technically "afford" basic needs on paper but lack the time to cook healthy meals, maintain a clean home, or maybe even spend time with their kids. These time constraints create a hidden burden, potentially trapping families in a cycle of "involuntary poverty."

It's not just about being busy

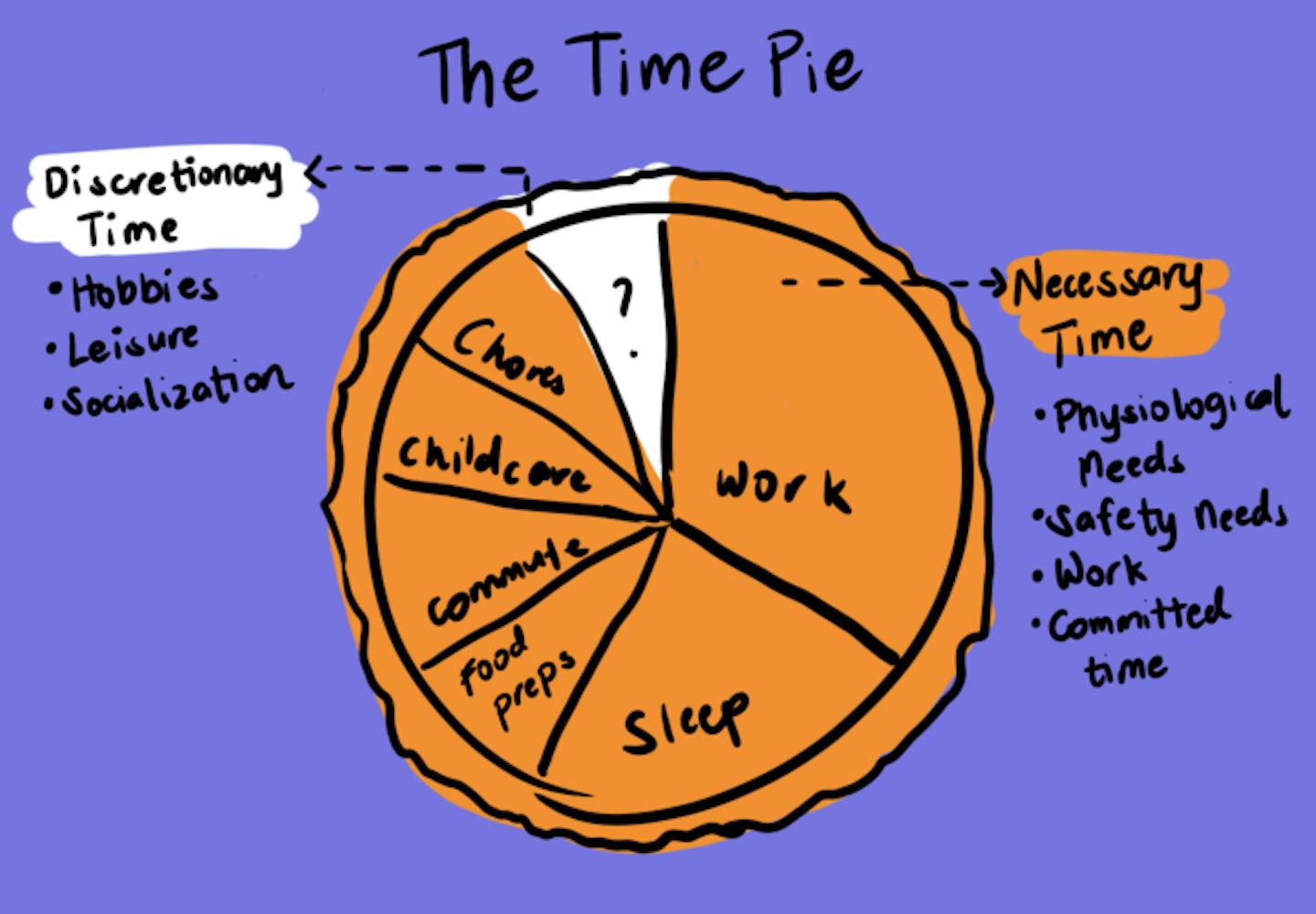

Time poverty isn't just about feeling perpetually busy. It's about the quality and quantity of time you have. Imagine your time as a pie. A big slice goes to necessary time: 2 the non-negotiables like sleep, hygiene, and keeping a roof over your head. This includes physiological needs (eating, sleeping), safety needs (security measures, home maintenance), contracted time (work that generates income), and committed time (activities performed given previous life choices, like parenting). Committed time in particular can feel like a double whammy—it's essential but often unpaid labor.

The remaining slice? That's your discretionary time:2 the golden hours for leisure, hobbies, and social connection. This is where time poverty hits. Someone with a mountain of committed time might have all their basic needs met but lack the free time to truly recharge or pursue their passions. This means you could be cash-rich yet time-poor, constantly scrambling for the hours that truly matter. This imbalance can lead to stress, burnout, and a feeling of being constantly strapped.

Moreover, many studies demonstrate how time poverty hammers your well-being down, leaving you with a scarcity mindset and relentless pressure to be productive. Let's unpack what this means for your health, your happiness, and of course, your ability to make good decisions.

References

- Vickery, C. (1977). The time-poor: A new look at poverty. The Journal of Human Resources, 12(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.2307/145597

- Williams, J. R., Masuda, Y. J., & Tallis, H. (2015). A measure whose time has come: Formalizing time poverty. Social Indicators Research, 128(1), 265-283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1029-z

- Kalenkoski, C. M., & Hamrick, K. S. (2012). How does time poverty affect behavior? A look at eating and physical activity. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 35(1), 89-105. https://doi.org/10.1093/aepp/pps034

- Spinney, J., & Millward, H. (2010). Time and money: A new look at poverty and the barriers to physical activity in Canada. Social Indicators Research, 99(2), 341-356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9585-8

- Yuan, Y., & Sun, X. (2024). Can't see the forest for the trees: Time poverty influences construal level and the moderating role of autonomous versus controlled motivation. British Journal of Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12730

- Ng, I. Y., Tan, Z. H., & Chung, G. (2024). Time poverty among the young working poor: A pathway from low wage to psychological well-being through work-to-Family-Conflict. Journal of Family and Economic Issues. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-024-09951-1

- Chaudhuri, S., Roy, M., McDonald, L. M., & Emendack, Y. (2021). Coping behaviours and the concept of time poverty: A review of perceived social and health outcomes of food insecurity on women and children. Food Security, 13(4), 1049-1068. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-021-01171-x

- Giurge, L. M., Whillans, A. V., & West, C. (2020). Why time poverty matters for individuals, organisations and nations. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(10), 993-1003. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0920-z

- Whillans, A., & West, C. (2022). Alleviating time poverty among the working poor: A pre-registered longitudinal field experiment. Scientific Reports, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-04352-y

- Sharif, M. A., Mogilner, C., & Hershfield, H. E. (2021). Having too little or too much time is linked to lower subjective well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 121(4), 933-947. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000391

- Kasser, T., & Sheldon, K. M. (2008). Time affluence as a path toward personal happiness and ethical business practice: Empirical evidence from four studies. Journal of Business Ethics, 84(S2), 243-255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9696-1

- Schaupp, J., & Geiger, S. (2021). Mindfulness as a path to fostering time affluence and well‐being. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 14(1), 196-214. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12298

About the Author

Celestine Rosales

Celestine is a Senior Research Analyst at The Decision Lab. She is a researcher with a passion for understanding human behavior and using that knowledge to make a positive impact on the world. She is currently pursuing her Master's degree in Social Psychology, where she focuses on issues of social justice. She also holds a Bachelor's degree in Psychology. Before joining TDL, Celestine worked as a UX Researcher at a conversion rate optimization company, where she collaborated with a variety of B2B and SaaS clients to help them improve their websites. She also participated in an all-women cohort of scholars trained to do data analytics. Outside of work, Celestine enjoys taking long walks, listening to podcasts, and trying new things.

About us

We are the leading applied research & innovation consultancy

Our insights are leveraged by the most ambitious organizations

“

I was blown away with their application and translation of behavioral science into practice. They took a very complex ecosystem and created a series of interventions using an innovative mix of the latest research and creative client co-creation. I was so impressed at the final product they created, which was hugely comprehensive despite the large scope of the client being of the world's most far-reaching and best known consumer brands. I'm excited to see what we can create together in the future.

Heather McKee

BEHAVIORAL SCIENTIST

GLOBAL COFFEEHOUSE CHAIN PROJECT

OUR CLIENT SUCCESS

$0M

Annual Revenue Increase

By launching a behavioral science practice at the core of the organization, we helped one of the largest insurers in North America realize $30M increase in annual revenue.

0%

Increase in Monthly Users

By redesigning North America's first national digital platform for mental health, we achieved a 52% lift in monthly users and an 83% improvement on clinical assessment.

0%

Reduction In Design Time

By designing a new process and getting buy-in from the C-Suite team, we helped one of the largest smartphone manufacturers in the world reduce software design time by 75%.

0%

Reduction in Client Drop-Off

By implementing targeted nudges based on proactive interventions, we reduced drop-off rates for 450,000 clients belonging to USA's oldest debt consolidation organizations by 46%