Why Most Organizational Change Programs Fail

Imagine you work in the IT department at Super Productivity Corporation.1 You and your colleagues wish to adopt an automated process for IT help, based on an electronic help desk that works through an app on the employee’s computer.

You have very good reasons to be excited about the process: it is much faster than the existing phone-in process and will save time for everybody. After all, efficiency is a core value at the Super Productivity Corporation. For this reason, you don’t anticipate any problems—but, just to be safe, you still take the time to inform all employees about this change through emails, luncheons, and workshop demonstrations of how it’s used and what the benefits are.

Launch day finally arrives. You and the others in the IT department arrive and sit back, ready to enjoy what is sure to be a nice, relaxing day at work. With the new system in place, the constant ringing of phones will be a thing of the past! But your hopes for a perfect day are shattered when a colleague comes knocking at the door to relay their technical issues, and in a somewhat agitated manner…

Behavioral Science, Democratized

We make 35,000 decisions each day, often in environments that aren’t conducive to making sound choices.

At TDL, we work with organizations in the public and private sectors—from new startups, to governments, to established players like the Gates Foundation—to debias decision-making and create better outcomes for everyone.

The human side of change

In a business environment (as anywhere else), the successful implementation of an organizational change is dependent on the willingness of affected people to comply, and on their ability to easily do so. Studies show that the majority of major corporate change programs fail, often because human resource barriers such as lack of employee involvement and motivation are overlooked.2

As human beings, it is in our nature to contemplate, question, and even resist change. If we are not able to consciously process the reasons for the specific change or accept that there is a need for things to be done in this new fashion, we often succumb to the status quo bias (our emotional preference for maintaining the current state of affairs) and consequently find ourselves resisting change—even when it might be helpful to us in the long run.

The human element of change is often overlooked, especially when the changes we want to see are themselves rather easy to implement. Think of moving to a new house: while the process of packing & unpacking is a hassle, the sofa, TV, and washing machine will operate and serve the same purposes in the new environment once offloaded from the van, no negotiation or pep talk necessary. But for the family members who are changing neighborhoods, schools, and routines, the process is much more difficult and involves cognitive and emotional elements. There is ambiguity, a sense of loss, fear of the unknown…

Behavioral barriers to organizational change

The same applies to any change within a company or organization that affects employees, from the introduction of a GDPR protocol or pandemic-induced processes, to organizational restructuring following a merger or acquisition. Interestingly, it also applies to smaller-scale events such as the adoption of new, fairly simple technologies or tools.

Research shows that 55% of our workday behaviors are habitual.3 In other words, half of what we do is to respond automatically to cues in a way that has yielded some kind of reward for us in the past. This behavior is desirable most of the time as it helps us navigate the world around us, making life easier and work more productive.

There are instances, however, when routines inhibit organizational change and innovation—which is exactly what happened at Super Productivity Corporation. When the employees ran into an IT problem, out of habit, they picked up the phone and called the IT help desk. But following the launch of the new app, that habit did not produce the desired result, and they started feeling stressed and frustrated.

When these negative feelings cascade throughout the organization, they can manifest as decreases in productivity and damage to employee morale. Organizations facing such a situation tend to find themselves spending substantial resources to temporarily recreate the old process and appease employees, while simultaneously trying to reintroduce the very simple (yet widely unpopular by now) new system.

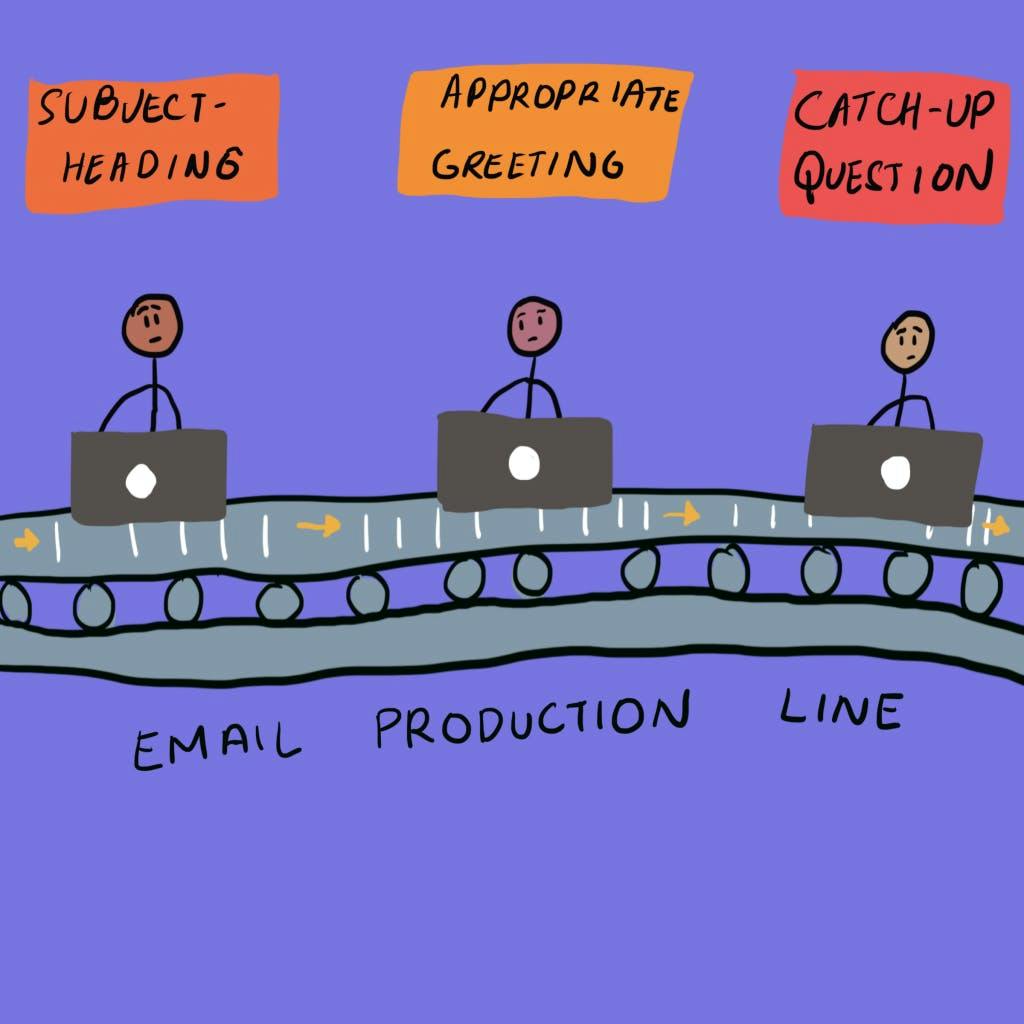

Going beyond habits, in our imaginary scenario, we can also think of a few other possible reasons for the failed transition to the helpdesk app by borrowing insights from further research.4 For instance, there could be an issue of information overload, which can lead to decision fatigue and reinforce employees’ tendency to cave into impulses and preformed habits (i.e. picking up the phone to report an IT problem).

In addition, there is often an issue of confirmation bias among the change architects. In the case of Super Productivity Corporation, the IT team, in all their excitement, may have ignored any contradictory or negative feedback from their colleagues, or brushed off employee concerns about implementing this change because they were so focused on the benefits it would bring.

Is there a better way?

Fortunately, insights from behavioral science5 provide a roadmap for facilitating change. Research points towards three well-established paths for new habit formation, which are not perceived as costly by the people who undergo the change.

- Make the alternative behavior easy to adopt. Possible ways to do this include adjusting the levels of sludge (obstacles that cost effort and time and accentuate the intention-action gap) and salience (prominence or noticeability) of the available options. In effect, this should decrease the value of the habitual response, and as the new behavior becomes easy to adopt, the change itself (as envisioned by its architects) becomes plausible.

A popular example is that of Google helping their employees develop healthier eating habits.6 To nudge employees towards healthier snack options, Google placed sugary sodas and chocolates behind an opaque sheet of glass (essentially out of sight) and put water, fruit, and nuts behind clear glass, at eye level. Over the seven-week test period, employees in the New York office consumed 3.1 million fewer calories from M&Ms, as well as 47% more water! - Make it personal by connecting the change to individual employees in relevant and meaningful ways. Realistically, it is not always possible to make the new behavior easy, especially as technological innovation sometimes requires the adoption of protocols that are more challenging to follow (at least at the outset). In such cases, personalization helps. For instance, practices of normative feedback (providing performance scores relative to others) can increase people's willingness to break away from habitual patterns in their quest to rank highly. This strategy relies on leveraging social norms which can help with behavior change.

- Make it about money. While a financial reward (or penalty) may not capture the whole story, it is still a powerful motivator. In the quest to change somebody’s habits, compensating them for their effort to engage in the new behavior can help offset their personal cost and be a powerful path to change. The inverse effect also works—that is, disincentives such as financial penalties applied to undesirable habits.

Conclusion

To sum up, in line with the experience of Super Productivity Corporation, many companies fall short of implementing changes successfully. And if such small changes as switching to an IT helpdesk app can cause widespread frustration, imagine what happens during extensive restructurings and digital transformations. We can attest that communicating the benefits of the change and training employees are necessary elements of the change management process, but this is still not enough to ensure uptake.

Instead, the success of any change management process depends on how individual people will choose to behave, their willingness to change their habits, and whether or not they have resources that will support them in doing so. This is where behavioral insights come to complement business strategy and change management tools to help the organizational engine—that is, the people who work there—succeed in the desired transition.

References

- Soman, D., Yeung, C. & Sunstein, C. (2021). The Behaviorally Informed Organization. University of Toronto Press.

- Mosadeghrad, Ali & Ansarian, Maryam. (2014). Why do organisational change programmes fail?. International Journal of Strategic Change Management. 5. 189. 10.1504/IJSCM.2014.064460.

- Wood, W. (2019). Good habits, bad habits: The science of making positive changes that stick. Pan Macmillan.

- Behavioural Economics in Action at Rotman, May 2021. How Can Leaders in Organizations Use Behavioural Science to Communicate and Support Their Teams Effectively? By Grace Lou, Sunny Xiang, Tony Kuang, Anirudh Ram-Mohanram, Kayln Kwan, Dilip Soman, Sonia Kang, and Bing Feng. Link to interactive document: https://indd.adobe.com/view/5d063c4a-0775-45f6-8894-9452da3c21d6

- Murray, K., & Chen, S. (2021). CHAPTER NINE Workplace Habits and How to Change Them. In The Behaviourally Informed Organization (pp. 155-169). University of Toronto Press.

- Kang, C. (2013). Google crunches data on munching in the office. Washington Post.

About the Author

Melina Moleskis

Dr. Melina Moleskis is the founder of meta-decisions, a consultancy that leverages management science and behavioral economics to help people and organizations make better decisions. Drawing from her dual background in business and academia, she works with determination towards uncovering pragmatic, sustainable solutions that improve performance for clients. Melina is also a visiting Professor of Technology Management as she enjoys spending time in the classroom (teaching as the best route to learning) and is always on the lookout for technology applications in behavioral science. In her prior roles, Melina has served as an economic and business consultant for 7 years in various countries, gaining international experience across industries and the public sector. She holds a PhD in Managerial Decision Science from IESE Business School, MBA in Strategy from NYU Stern and BSc in Mathematics and Economics from London School of Economics.