Why do we think less about some purchases than others?

Mental Accounting

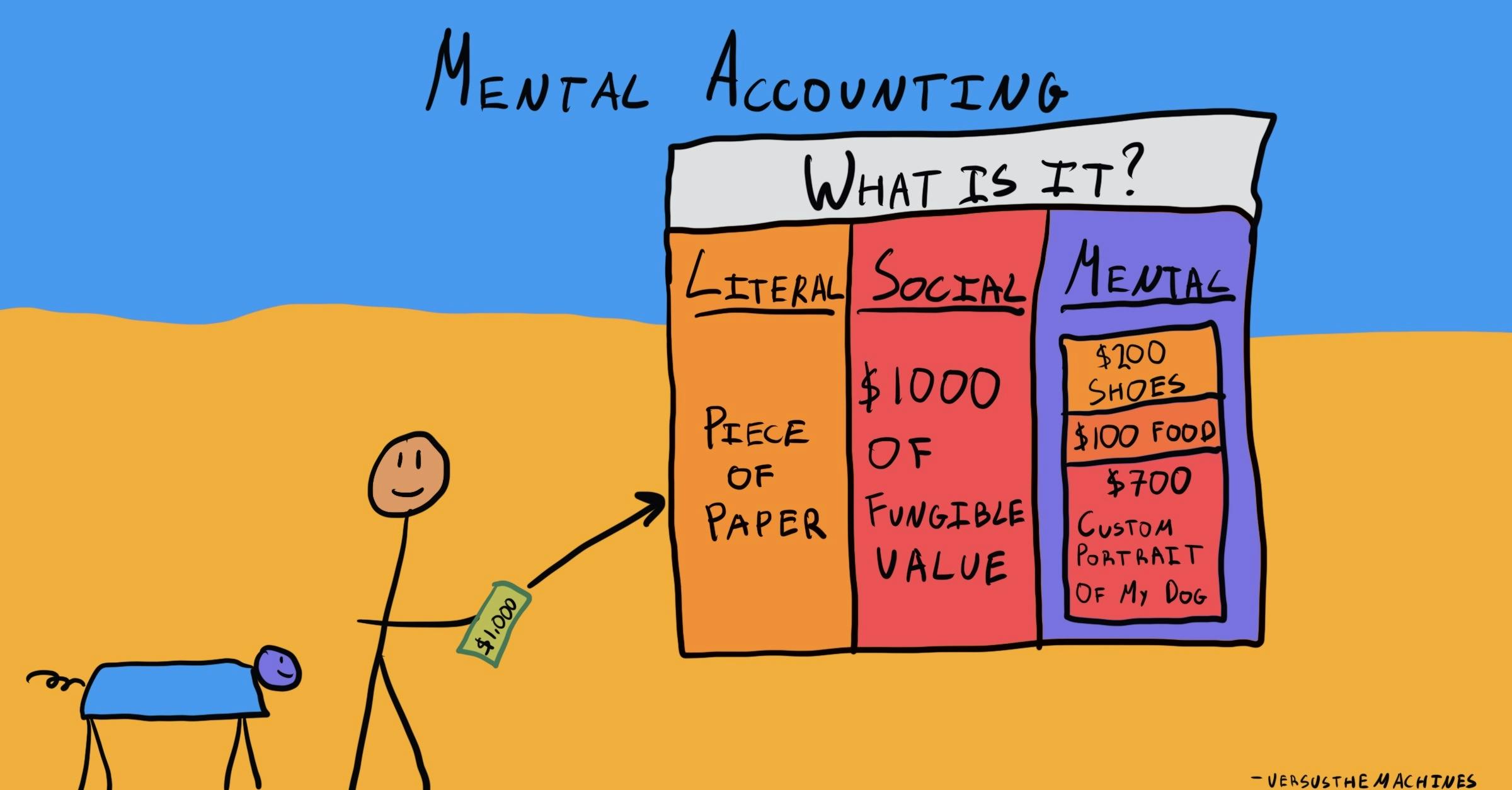

, explained.What is Mental Accounting?

Mental accounting, also known as mental accounting theory, explains how we tend to assign subjective value to our money, usually in ways that violate basic economic principles.1 Although money has consistent, objective value, the way we go about spending it is often subject to different rules, depending on how we earned the money, how we intend to use it, and how it makes us feel.

Where this bias occurs

Imagine you’re walking down the street, and you happen to find a $100 bill lying on the sidewalk. Ordinarily, you’re a pretty frugal person, and you’ve been trying to save some money to put towards buying a car in the future. Today, however, you take your newfound $100 and put it towards an expensive dinner. You tell yourself that this money isn’t “car money”—this is a one-off, special occasion, so why not treat yourself to a nice evening out? Your mental categorization of the $100 bill as different is an example of mental accounting at work.

Mental accounting is a concept from behavioral economics that describes how individuals categorize, evaluate, and manage money in different mental “accounts” rather than treating all money as fungible (easily interchangeable with something else of the same kind and value). One common distinction is between "happy money" (such as windfalls, birthday money, or bills found on the street) and "unhappy money" (the hard-earned money we use for utilitarian consumption).23 Mental accounting can lead to irrational financial behaviors, such as overspending, misallocating resources, or making riskier decisions with "found money." Understanding this cognitive bias, and the effect it has on us, can help individuals and organizations make better financial choices by treating money more objectively.

Although commonly associated with finances and budgets, mental accounting can also extend beyond money. People often create mental categories for different aspects of their lives, such as time, effort, and emotional investments, influencing how they make decisions and allocate resources.

Take time management, for instance. Depending on the context and the activity, we often treat time very differently. An individual might willingly spend hours binge-watching a favorite TV series but feel reluctant to spend the same amount of time learning a new skill, even if both activities are forms of personal investment. The same applies to emotional effort. Even if we feel exhausted after a long workday, we might still find the energy to socialize with friends because we categorize work-related exhaustion differently from social exhaustion.