Why do we value items more if they belong to us?

Endowment Effect

, explained.What is the Endowment Effect?

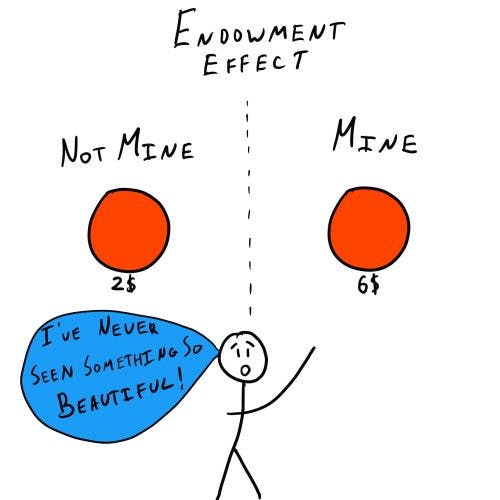

The endowment effect describes how people tend to value items that they own more highly than they would if they did not belong to them. This means that sellers often try to charge more for an item than it would cost elsewhere.

Where this bias occurs

Let’s say a few months ago, you bought a concert ticket for $100. You just found out that you won’t be able to make it to the concert after all, so you decide to resell your ticket. You price the ticket at $150, because just selling it at market value would feel like you were losing out.

Debias Your Organization

Most of us work & live in environments that aren’t optimized for solid decision-making. We work with organizations of all kinds to identify sources of cognitive bias & develop tailored solutions.

Individual effects

The endowment effect can impact us both as buyers and as sellers. On the one hand, this bias is easily exploited by marketers and salespeople: any tactic that makes us feel a sense of psychological ownership over a product can encourage us to spend more on it. On the other hand, as sellers, the endowment effect can lead us to price things unreasonably, based on a misguided sense that if we don’t, we’ll lose out.

Systemic effects

The endowment effect can cause us to overspend when we’re buying things, leading to extra costs that add up over time. Meanwhile, this bias can lead to opportunity costs—that is, gains that we miss out on—if it causes us to overprice our old stuff to the point where we don’t sell it.

Why it happens

The endowment effect is usually explained as a byproduct of loss aversion—the fact that we dislike losing things more than we enjoy gaining them.

Because of loss aversion, when we’re faced with making a decision, we tend to focus more on what we lose than on what we gain. As a result, in general, we are biased to maintain the status quo, rather than shake things up and risk sustaining losses. In one experiment by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, two of the founding fathers of behavioral economics, participants were asked to imagine that they were in one of two jobs—let’s call them Job A and Job B. They were told they’ve been offered the option of moving to the other job, A or B. The new job was better than their current one in one aspect, but was worse in another. Kahneman and Tversky found that regardless of which job they started out in, most people did not want to move to the other one.2

Another aspect of loss aversion is the fact that, when we make decisions, we usually under-value opportunity costs. Opportunity costs are benefits that we miss out on when we choose one alternative over another, as opposed to out-of-pocket costs, which is the direct payment you make in a transaction. In the endowment effect, when we try to overcharge a buyer for something we own, it is partially because we are more focused on the out-of-pocket cost (losing that item) than we are on the money we miss out on if the buyer doesn’t agree to our price.1

Buyers and sellers value things differently

Although the endowment effect was originally attributed entirely to loss aversion, other researchers have suggested a few other explanations that are better supported by evidence. One of these comes from a 2012 paper by Ray Weaver and Shane Frederick, who argue that the endowment effect actually happens because people are trying to avoid getting suckered into a bad deal. This view is known as reference price theory.

According to this view, when buyers and sellers approach a transaction, they often have different reference prices, or ideas about how much something is worth. Buyers don’t want to pay more than they think an item is worth, but sellers don’t want to sell for less than that item’s market price.3 So, for example, if you were trying to sell something that normally retails at $5, you probably wouldn’t want to settle for anything less than that, because then you would feel like you’re losing out. However, for a buyer who’s just casually interested in getting your item, $2.50 might be the most they are willing to pay.

In other words, the endowment effect happens when there’s a gap between a buyer’s willingness to pay and a seller’s willing to accept a certain price. Sometimes this gap appears because, when trying to decide what a reasonable price for something is, buyers will look to the lowest available price as a reference point, while sellers look at the highest ones. For example, if you were reselling a $250 ticket for a basketball game, and you saw that some people were reselling similar seats for $400, you might feel like a sucker if you sold for less than that. Meanwhile, people who are looking to buy tickets like yours see that others have gone for closer to the original price, and so they’re not willing to pay your higher price.4

Our positive self-concepts spill over to our possessions

Another possible driver of the endowment effect stems from the fact that we tend to like things more when we associate them with ourselves. Whether it’s justified or not (and it’s very often not), we are biased to see ourselves in a positive light, and we often believe that we are exceptional in various ways. Research has shown that this view of ourselves even extends to items that we own. This is known as the mere ownership effect.5

In one study looking at the mere ownership effect, university students who participated in the study were told they were taking part in a consumer preference study, and their job was simply to rate the attractiveness of a bunch of different products, including items like chocolate, a key ring, and soap. One of the items was a plastic drink insulator—a tube you can put around cans to keep them cold. To investigate whether people felt more strongly about items they owned, some of the participants were told they would be given a drink insulator as a “thank you” gift for participating.

If a plastic tube sounds like it would be a boring present to receive, you’re right: researchers chose it because they had found, in a separate study, that people’s feelings about the drink insulator were pretty much neutral. As unexciting as this item ordinarily is, the researchers found that participants who received it as a gift rated it as more appealing, compared to participants who were not offered a gift.5

One interesting aspect of this theory is that people have an even stronger need to enhance their mental image of themselves if they feel like their self-concept is being threatened. Indeed, one study found that after getting a bad rating for their performance on a task, people who had been given a drink insulator as a gift rated it as more appealing, compared to people who had not received negative feedback.5

Psychological ownership is different from actual ownership

Even if something doesn’t technically belong to us, we might still feel like it’s somehow ours. A lot of research has explored how much it takes for us to develop a sense of ownership over something, and the answer turns out to be not very much. This means that there is also a pretty low threshold for the endowment effect to kick in.

In one experiment, researchers gave each participant a chocolate bar, placing it on their desk—but also telling them they weren’t allowed to eat it. For thirty minutes, the participants worked on a project, with the chocolate bar staring them down all the while. Finally, when the project was done, the researchers told the participants that the chocolate bar was theirs. But before they left, people were given a choice: to keep the chocolate, or to sell it back at a price they determined.

On average, participants who sold the chocolate bar back sold it for $1.72. However, in another group, where the chocolate bar was merely handed to people as a reward at the end of the project instead of sitting on their desks for half an hour, people only valued the chocolate at $1.35.7 That’s the endowment effect at work.

As this study shows, psychological ownership can spring up really easily. Other research has found many other ways that people can be made to feel a sense of ownership, including being allowed to touch a product before buying it.6

Why it is important

The endowment effect is something that marketers and salespeople can try to exploit in order to sell products more easily. Any sales tactic that tries to inspire a sense of ownership or personal connection to a product is based on the endowment effect: if we feel a sense of psychological ownership, we’ll be willing to pay more for something. As consumers, being aware of this bias helps us recognize times when we are being manipulated, and stop ourselves from overspending.

On the flipside, for people trying to sell their things—whether it’s a used car or a concert ticket—the endowment effect can stand in the way of striking a deal that benefits both parties. This can mean big opportunity costs in the long run, if unreasonably high prices end up deterring potential buyers.

As we’ve seen, there are many possible explanations for the endowment effect, but at the end of the day, they are all based in logic that is flawed. In the case of loss aversion, we’re focusing too much on the pain of losing something and failing to think about what we’ll gain by selling it. With reference price theory, even if an item doesn’t mean very much to someone personally, they might be unwilling to sell it for anything less than an unreasonably high price, because then they feel like they’re losing out. And with the mere ownership effect, we falsely believe that our stuff must be especially awesome, because we are especially awesome.

Once we’re aware of the endowment effect, we can take steps to avoid it, and catch ourselves when we’re being led astray by faulty reasoning.

How to avoid it

Beware of psychological ownership

When buying a new car, it’s common for salespeople to encourage customers to imagine themselves driving around in a particular model, and of course to let people take cars for test drives. Granted, being able to test drive a car before you buy it is important to get a feel for it—but these tactics are also in place to encourage psychological ownership. The more time you spend using and interacting with a product, the more it starts to feel like yours, and the harder it is to part with it.

Be aware of sales tactics and salespeople who try to make you “bond” with products in this way.6 And when you do run into them, try to keep in mind that this very brief interaction with a product does not make it superior to your other options, and doesn’t necessarily mean this item is worth forking out a bunch of extra money for.

Try to consider opportunity costs

When trying to sell something, you may be inclined to price it higher than the average market value—maybe because it has sentimental value, or maybe because you don’t want to miss out on money you could potentially make by charging so much. But keep in mind that pricing your item higher than market value, or at the higher end of what people typically sell it for, is going to make it more difficult to attract a buyer—especially if they can get the same thing somewhere else, for cheaper. It’s better to sell something for close to what it’s worth than to not sell something at all.

Base your prices on market value

As a seller, one of the most straightforward ways to avoid falling prey to the endowment effect is to keep closer to market value. In their paper, Weaver and Frederick show that when both parties value the item at its market price, the endowment effect no longer happens.3 If there’s a range of prices that that this item is usually sold for, try to stay close to the middle of that range: when buyers and sellers both have moderate reference prices in mind, there tends to be a smaller gap between the buyer’s willingness to pay and the seller’s willingness to accept.

How it all started

The term “endowment effect” was coined by the Nobel prize-winning economist Richard Thaler in 1980. Thaler often collaborated with Daniel Kahneman and Avos Tversky, and the endowment effect is a good example of how their research often overlapped: as Thaler was writing about the endowment effect and other economic phenomena, Kahneman and Tversky were writing about loss aversion and other cognitive biases that affect consumers’ decision making.

At the time when Richard Thaler started writing about it, the endowment effect was a challenge to standard economic theory. According to mainstream thinking in economics, the price a buyer was willing to pay for something should be equal to their willingness to accept the loss of that item. In other words, buying and selling prices were supposed to coincide.2 Research on the endowment effect demonstrated that this was not necessarily true.

Example 1 - Individualistic cultures

Generally speaking, cultures can be classified as individualistic or collectivistic. In individualist societies, people tend to value, well, individuals, as well as independence and self-expression. Collectivist societies, meanwhile, focus more on the group, emphasizing the collective good and valuing cohesion. While members of individualistic cultures tend to think very highly of themselves, people in collectivistic cultures tend more toward self-criticism than self-enhancement.7

Researchers were curious about how this difference would affect the endowment effect. So, they recruited people from Western cultures, as well as East Asian cultures, and had them participate in an experiment. (Western cultures are generally more individualistic, while East Asian cultures are more collectivistic.) During the study, one participant (the seller) was given a mug, and given the option to either keep the mug or sell it to the buyer. Both the buyer and seller then filled out a sheet with a range of prices on it, writing for each one whether they would be willing to buy or sell the mug.

The researchers found that, although the endowment effect was present in both Westerners and East Asians, it was significantly stronger in the Western participants. This is more evidence that the endowment effect is often driven by ego: if we think highly of ourselves, we think more highly of our stuff, too.

Example 2 - Across species

Research has shown that our primate cousins are also subject to the biases that cause the endowment effect. In one experiment, researchers gave capuchin monkeys tokens for them to spend on food, and then offered them a choice between two treats that they equally enjoy: fruit discs and cereal cubes.8 After the monkeys picked one of these treats, they could either eat it, or they could trade it back in exchange for the other alternative—so, if the monkey had picked the fruit, they could trade it for the cereal. Very few monkeys opted to trade their food item.

The researchers reran the experiment a few times, making slight changes. In one version, after the monkeys had picked their treat, they were given the opportunity to trade it for the other option, plus an extra bonus: a single oat. (The researchers had already made sure that ordinarily, the monkeys were willing to pay one whole token in exchange for one oat.) Even still, the vast majority of monkeys did not want to trade.

Summary

What it is

The endowment effect is the tendency for us to assign more value to an object when we own it, compared to how we would value the same item if it belonged to someone else.

Why it happens

There are multiple explanations for the endowment effect, all of which might contribute to different degrees in different situations. Loss aversion leads us to focus more on the pain of losing an item than on the satisfaction of gaining money for it; buyers often have different reference prices in mind for an item, which leads to gaps in their willingness to pay or accept a price; and finally, it is very easy for us to develop a sense of psychological ownership over something, which makes us feel more positively about it.

Example 1 - The endowment effect is stronger for individualists

People from individualistic cultures are more likely to self-enhance than people from collectivistic cultures. Research suggests that this leads to stronger endowment effects in Westerners than in East Asian people.

Example 2 - Capuchin monkeys also show the endowment effect

In an experiment where capuchin monkeys could trade a treat for another, equally appealing treat, they rarely chose to do so—even if they were also offered a bonus oat. Imagine passing up a bonus oat!

How to avoid it

To avoid the endowment effect, beware of sales tactics that encourage psychological ownership, and be mindful of market prices when trying to decide how much to sell for.

Related articles

This Is Your Brain On Money

This article explores the psychological aspects of paying for things with cash, rather than a credit card. One factor is the endowment effect. Research has shown that if people paid for an item using cash, they said they would charge a higher price for it, on average, if they were to sell it. This suggests that we feel somehow more connected to purchases made with cash, which strengthens the endowment effect.

A Better Explanation of the Endowment Effect

This article goes into greater detail about the reference price theory of the endowment effect, and why it is better supported than the classical explanation of loss aversion.