Health Belief Model

What is the Health Belief Model?

The Health Belief Model (HBM) is a behavioral science framework that helps to explain and predict health behaviors by focusing on people's perceptions of health. This model identifies six key factors that influence whether a person will take action to prevent, screen for, or control illness. However, health-related decision-making is complex, involving a combination of scientific evidence, personal experiences, and emotional and social influences.

The Basic Idea

Imagine that you come down severely with the flu. You have a few options to get yourself back to a healthy state:

- Buy over-the-counter medicine from your local pharmacy

- Book an appointment to visit your General Practitioner.

- Try a “homemade remedy” your friend swears by.

Which option are you likely to choose? According to the HBM, you’ll probably go with option one. You feel bad enough to take action, there are few perceived barriers (it’s faster and easier than visiting your GP), and you trust in the benefits (more so than your friend’s so-called remedy).

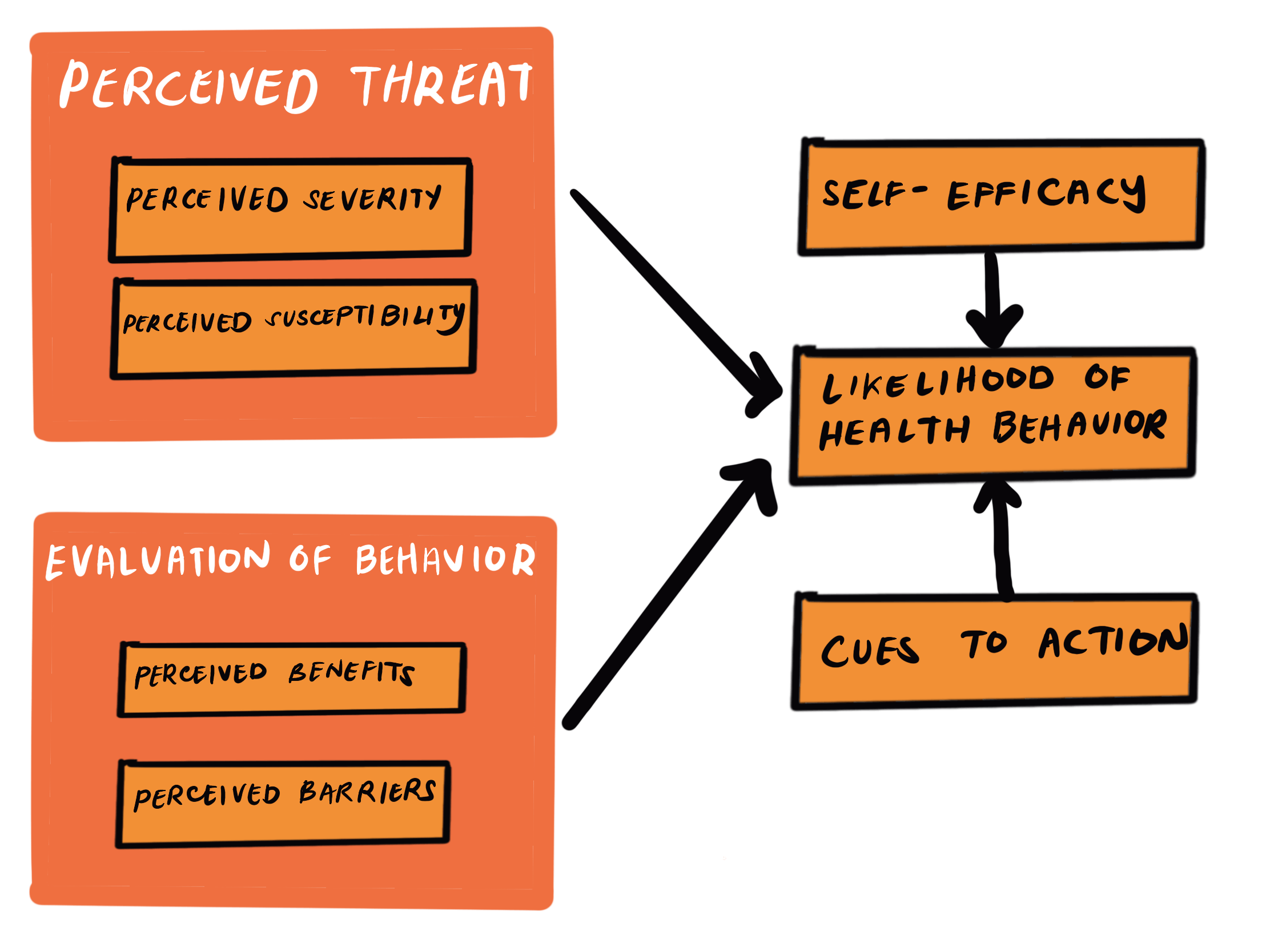

The Health Belief Model (HBM) suggests that people’s willingness to change their health behaviors is significantly influenced by their perceptions related to health. By examining how individuals perceive the threat of illness, the benefits and effectiveness of changing behavior, and the barriers to making those changes, the HBM helps predict (and design interventions to change) health behaviors. The model identifies six key factors that drive these behaviors.1: perceived severity, perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, self-efficacy

“People use a common-sense approach to manage their health, where perceptions of illness shape coping strategies and health outcomes.”

Howard Leventhal, Canadian social psychologist who helped to create the Health Belief Model.2

About the Author

Emilie Rose Jones

Emilie currently works in Marketing & Communications for a non-profit organization based in Toronto, Ontario. She completed her Masters of English Literature at UBC in 2021, where she focused on Indigenous and Canadian Literature. Emilie has a passion for writing and behavioural psychology and is always looking for opportunities to make knowledge more accessible.