System 1 and System 2 Thinking

What is System 1 and System 2 Thinking?

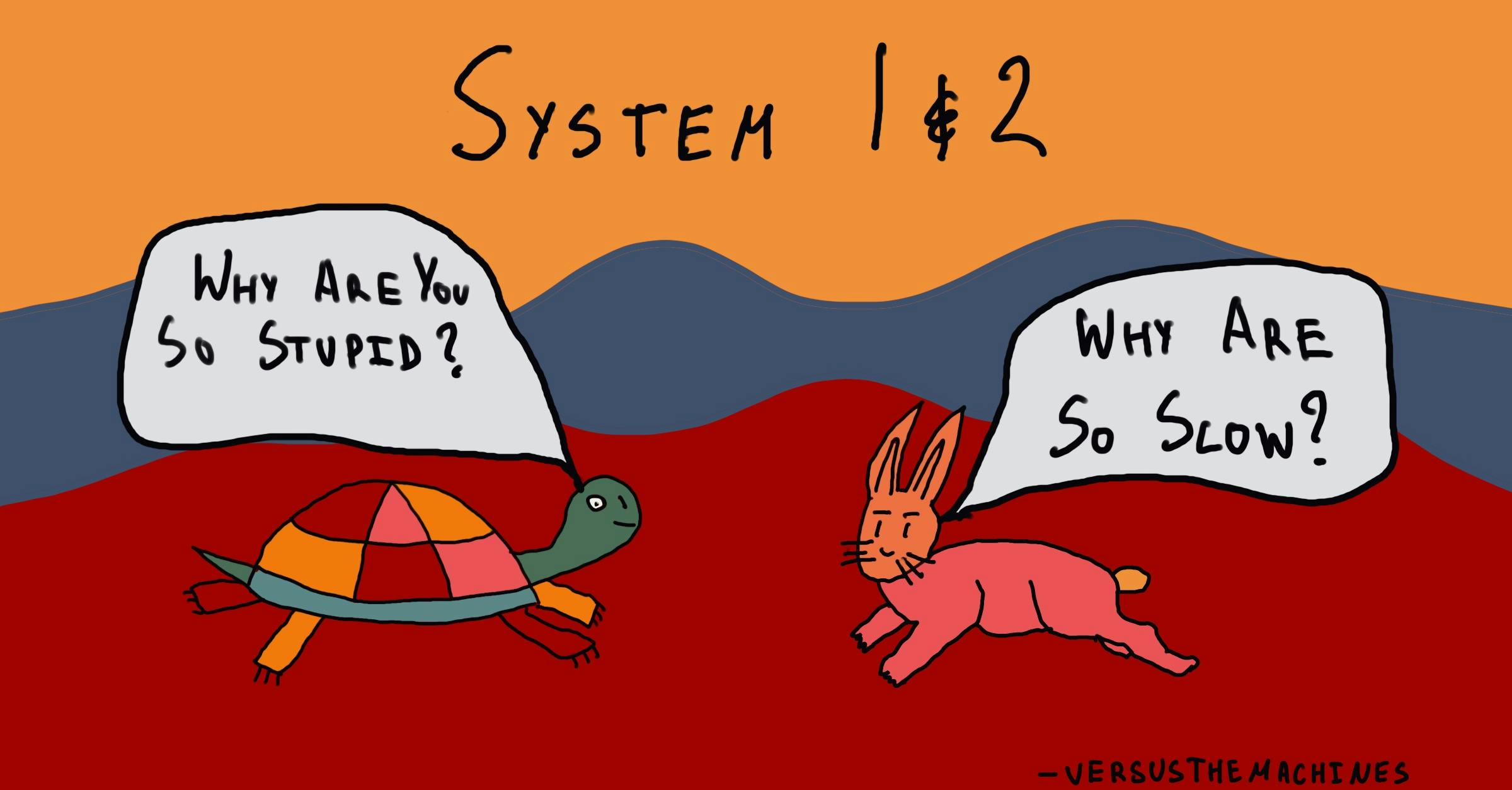

System 1 and System 2 thinking describes two distinct modes of cognitive processing introduced by Daniel Kahneman in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow. System 1 is fast, automatic, and intuitive, operating with little to no effort. This mode of thinking allows us to make quick decisions and judgments based on patterns and experiences. In contrast, System 2 is slow, deliberate, and conscious, requiring intentional effort. This type of thinking is used for complex problem-solving and analytical tasks where more thought and consideration are necessary.

The Basic Idea

When commuting to work, you always know which route to take without having to consciously think about it. You automatically walk to the subway station, habitually get off at the same stop, and walk to your office while your mind wanders. It’s effortless. However, the subway line is down today.

While your route to the subway station was intuitive, you now find yourself spending some time analyzing alternative routes to work in order to take the quickest one. Are the buses running? Is it too cold outside to walk? How much does a rideshare cost?

Our responses to these two scenarios demonstrate the differences between our instantaneous System 1 thinking and our slower, more deliberate System 2 thinking.

However, even when we think that we are being rational in our decisions, our System 1 beliefs and biases still drive many of our choices. Understanding the interplay of these two systems in our daily lives can help us become more aware of the bias in our decisions—and how we can avoid it.

The automatic operations of System 1 generate surprisingly complex patterns of ideas, but only the slower System 2 can construct thoughts in an orderly series of steps.

– Daniel Kahneman in Thinking, Fast and Slow

About the Author

Joshua Loo

Joshua was a former content creator with a passion for behavioral science. He previously created content for The Decision Lab, and his insights continue to be valuable to our readers.