The Butterfly Effect

What is the Butterfly Effect?

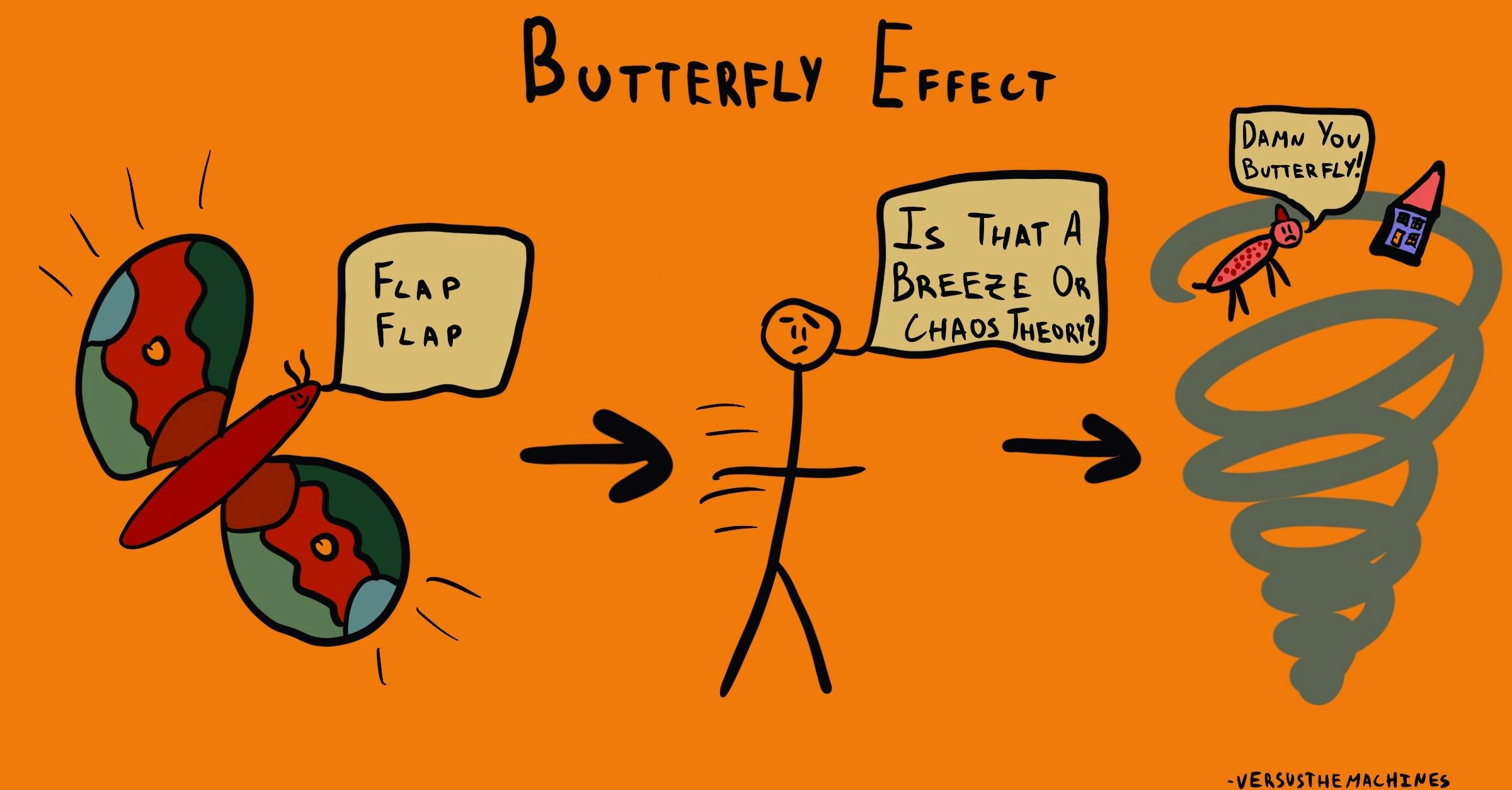

Rooted in chaos theory, the butterfly effect describes how a tiny change in the initial stages of a system can cause huge, non-linear consequences elsewhere over time. Mathematician and meteorologist Edward Norton Lorenz originally explained this theory metaphorically, suggesting that a flap of a butterfly’s wing in one corner of the world could cause a tornado elsewhere weeks later.

The Basic Idea

The world is vast and complex and it may sometimes seem that our small decisions and actions have little to no impact on the big picture. However, if you think about minute details of your life, you may be able to see how a small event was actually the catalyst for a huge change in your life. For example, maybe you bumped into someone at a coffee shop that happens to work at your dream company and eventually got you an interview there. What if you had chosen a different coffee shop, or been there five minutes later? You may not have met the person that got you into your dream job. The idea that something small, like getting coffee, can have much larger effects, such as altering your career is called the butterfly effect.

The butterfly effect is a property of our incredibly complex, deeply interconnected world, such that one small occurrence can influence a much larger complex system. The effect is named after an allegory in chaos theory; it evokes the idea that a small butterfly flapping its wings could, hypothetically, cause a typhoon. Or it could not – the mind-boggling part of the butterfly effect is that it’s virtually impossible to predict whether a small system will lead to chaotic behavior.1

While the butterfly effect has taken up an altered definition in popular media and everyday use, a more accurate version explains that small changes in one part of an interconnected system can cause disproportionately large outcomes elsewhere, setting off a chain of events that can lead to unpredictable results. Originating in the complex field of weather modeling, the butterfly metaphor was initially used to illustrate how seemingly inconsequential changes in the starting conditions of a weather model could result in significant differences in outcome. This realization underscored the difficulty of making predictions in complex systems like weather.

Today, the butterfly effect is widely referenced outside the context of weather science. It is now used more broadly to refer to situations where small changes cause large consequences. The effect has been applied to economics, environmental science, and even mental health—though it's sometimes incorrectly used to state that small changes can lead to predictable consequences (similar to the coffee shop example provided above). While people often misinterpret the original meaning of the butterfly effect, popular culture has largely embraced the metaphor to explain the powerful interconnectedness of life on Earth.

It used to be thought that the events that changed the world were things like big bombs, maniac politicians, huge earthquakes, or vast population movements, but it has now been realized that this is a very old-fashioned view held by people totally out of touch with modern thought. The things that really change the world, according to Chaos theory, are the tiny things. A butterfly flaps its wings in the Amazonian jungle, and subsequently a storm ravages half of Europe.

– From Good Omens by Neil Gaiman and Terry Practchett1

About the Authors

Dan Pilat

Dan is a Co-Founder and Managing Director at The Decision Lab. He is a bestselling author of Intention - a book he wrote with Wiley on the mindful application of behavioral science in organizations. Dan has a background in organizational decision making, with a BComm in Decision & Information Systems from McGill University. He has worked on enterprise-level behavioral architecture at TD Securities and BMO Capital Markets, where he advised management on the implementation of systems processing billions of dollars per week. Driven by an appetite for the latest in technology, Dan created a course on business intelligence and lectured at McGill University, and has applied behavioral science to topics such as augmented and virtual reality.

Dr. Sekoul Krastev

Dr. Sekoul Krastev is a decision scientist and Co-Founder of The Decision Lab, one of the world's leading behavioral science consultancies. His team works with large organizations—Fortune 500 companies, governments, foundations and supernationals—to apply behavioral science and decision theory for social good. He holds a PhD in neuroscience from McGill University and is currently a visiting scholar at NYU. His work has been featured in academic journals as well as in The New York Times, Forbes, and Bloomberg. He is also the author of Intention (Wiley, 2024), a bestselling book on the science of human agency. Before founding The Decision Lab, he worked at the Boston Consulting Group and Google.