Creating Great Choices with Roger Martin

It’s not just about knowing the process and having the skills. It’s about your approach, and from the way that you describe it, your respect for other people. That you need to be able to truly believe and embrace the idea that a reasonable person can hold a different view.

Intro

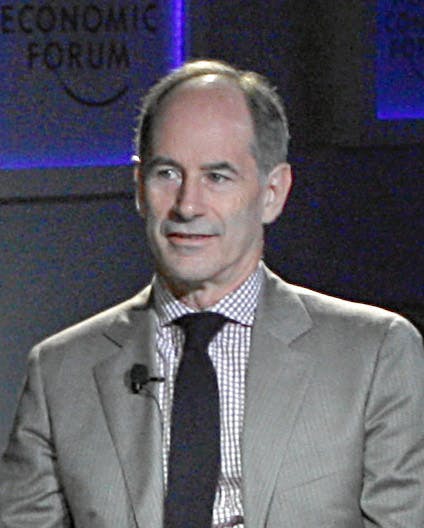

In this episode, Brooke is joined by Roger Martin, an experienced strategy advisor, former Dean of the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto, and co-author of Creating Great Choices. Together, the two explore business models and how we can make great choices when faced with incongruity. Supported with real-world examples, the discussion addresses how we should move forward when we don’t get the outcomes we hoped for.

Some specific topics include:

- Our disinclination toward compromise and how to get around making “either/or” decisions

- Bob Young and his company Red Hat, who took two unappealing choices and built a superior model amidst the free software movement

- The ladder of inference that leads us to focus on monoliths

- How the Toronto International Film Festival overcame the power of monoliths and became the most important film festival in the world

- The three steps for integrative thinking, an alternative to accepting polarized situations

- How Roger transformed the Rotman School of Management into one of the highest-ranked business schools in research

- How people can work toward integrative thinking through their everyday choices

The conversation continues

TDL is a socially conscious consulting firm. Our mission is to translate insights from behavioral research into practical, scalable solutions—ones that create better outcomes for everyone.

Key Quotes

On Roger’s work:

“I’ve sort of made it my career’s work to explore when people have models that don’t produce the outcomes that they were hoping for … I ask the question: is the model that you’re using actually getting you that outcome? Or is it actually not and you think trying harder, doing more of it, will get you the answer.”

On our disclination toward compromise:

“For what it’s worth, I’m very sympathetic with the hate for compromise. It’s sort of like you don’t get what you want, I don’t get what I want, and we settle for something blah in between. So the idea that people should love compromise, I think, is sort of far-fetched.”

On moving past compromise to combine opposing models:

“If you look beneath it and say, ‘Well, how does that model work? How does this model work? Oh, we can take that piece and that piece, and put them together in a new way,’ you get a better model.”

On our inclination to focus on monoliths:

“This is something that a great, now late, scholar named Chris Argyris talked about back in the 70s: people have a ladder of inference in their mind. People are built to make decisions … What Chris said is that we start at the lowest level from data, what he called directly observable data … Then we add inferences … So those people and organizations who do what we’ve been describing – which is to come to these sort of Balkanized views – are just following their ladder of inference.’

On the difference between integrative thinking and negotiation:

“Integrative thinking is not negotiation. I don’t want to have the view being, ‘You and I have to negotiate with one another because we think differently.’ ‘You and I have to create something magical together,’ is more what I want.”

On viewing opposing ideas as evil:

“If you have a mindset that says opposing ideas are the product of stupid or evil people, you’ll be stuck, unfortunately, having a relatively miserable life.”

On a successful life:

“If you want to be successful in life, you should try to convince yourself to always go forward with the, ‘I have a view worth hearing, but I might be missing something.’”

Transcript

Brooke Struck: Hello everyone, and welcome to the podcast of The Decision Lab, a socially conscious applied research firm that uses behavioral science to improve outcomes for all of society. My name is Brooke Struck, research director at TDL, and I’ll be your host for the discussion. My guest today is Roger Martin, former Dean of the Rotman School of Business at the University of Toronto, author of over a dozen best-selling business books, and long-time strategy advisor to global brands such as Procter & Gamble, Lego, and Ford. In today’s episode, we’ll be talking about Creating Great Choices: coming up with options that are better than the ideas already on the table. Roger, thanks for joining us.

Roger Martin: Hey, it’s a pleasure. It’s great to be here, and I think you and I sound like we’re interested in some of the same things. I’m always interested in models – how people think they should think about something – and I’ve sort of made it my career’s work to explore when people have models that don’t produce the outcomes that they were hoping for. So I don’t quibble with the outcomes that they’re hoping for, but I ask the question: is the model that you’re using actually getting you that outcome? Or is it actually not and you think trying harder, doing more of it, will get you the answer.

And you refer to Creating Great Choices. That’s a book about a model that says, “Well, if you have a really difficult choice, if you’re a real tough guy, or tough gal, you’ll just knuckle down and make that hard, hard choice.” And that’s our model. And my question is, well, might there be a better model? Might there be a model that says, “You know what? Maybe that’s life’s way of telling you, you should do something different than make that difficult choice.” So that’s kind of what I do in life.

Brooke Struck: Yeah, that’s a great introduction. I think that concept of toughness is a great place to start. So leadership in a lot of public and private sector contexts seems to include three truths, which we hold to be self-evident. People hate compromise, people hate flip-flopping, and you can’t please everyone. Those seem to be core ingredients to the model of making tough decisions. What kinds of decision dynamics did these mantras, and others like them, create within organizations, especially around these apparently “either/or” decisions?

Roger Martin: Well, I think it’s in part behind some of the polarization that’s gone on in politics. Where, because people hate compromise – and for what it’s worth, I’m very sympathetic with the hate for compromise. It’s sort of like you don’t get what you want, I don’t get what I want, and we settle for something blah in between. So the idea that people should love compromise, I think, is sort of far-fetched. So the general view – especially in the political realm – is then, we have to fight as hard as we can to have our side win, even if it’s 50.1% of the electorate saying, “So at least we’ve prevailed.”

And I think that just turns people into enemies, so other ideas are sort of alien creatures that it would be better off if we could somehow destroy. It leads to all of those behaviors that you’re seeing writ large out there. My view is that what passes up is huge treasure troves of pieces or chunks of ideas that you could actually take from the opposing model and figure out how to create something that’s better than either party contemplated, and then you don’t have compromise. You don’t have winners and losers – although you have winners, which is everyone. But you don’t have losers.

But that requires, as I referred earlier, a different model that says, “My job is not to make sure my model trounces yours. Intellectually, I could out-argue you, or I can get more people behind me than you can get behind you, so we overwhelm you.” It says, “Those actually aren’t my jobs. My job’s a miner: I’m mining your model for all the nifty tidbits in it that could be integrated into a superior model.”

Brooke Struck: Yeah, we’ll dig into that better model a little later on. First, let’s mine the problem a little deeper. It might be helpful to introduce an example here. So do you have some examples in mind of classic, seemingly either/or decisions, where we do what it is that you’ve just described? So we arrange ourselves into camps “for” and “against.” We kind of quell any ideation or discussion of what other options might exist.

Roger Martin: Well, since you’re broadcasting from Canada, I’ll give you a Canadian example, which is Bob Young, who’s the Canadian who was a co-founder of Red Hat, which became – and is still 26 years later – the dominant software company. In fact, it sold to IBM for $30 or $40 billion. If you scroll back to 1995, there was this free software movement that had cropped up. The dominant software, of course, in the operating system world, was Microsoft Windows – and it was classically proprietary software. They would sell you a copy of Windows 95, at that time, for a couple hundred bucks. They didn’t give you the source code, so you could not modify it in any way, and it had a license so that you put it on your computer, nobody else’s, and they had hit squads to go around and shoot anybody who gave it to anybody else…

Well, not quite, but close, and the free software movement hated everything about that. So they were taking Linux codes, compiling software packages. They had weird names like Yggdrasil, which was a Norse god, or Slackware, which is a bunch of slackers doing it. They would sell a disc of this free software, and as Bob said, it wasn’t free as in free beer, it’s free as in you can do anything you want with it, for $15 or $20.

It was $300 for proprietary and shrink-wrapped software that you’d sell out of your basement, and both sides kind of hated one another. The free software movement stood against what Microsoft was: the “evil empire.” Microsoft saw these guys as a threat to their business and they were hackers that sold crappy software that didn’t have quality control, version control, and all that stuff.

So Bob is facing that, and the problem is that he stands against everything that Microsoft stands for. He said it’s like selling a car with the hood welded shut, so that you can’t fix it when it needs to be fixed. But he looks at all the free software players and says, “They’re all people in garages getting nowhere, and the only people who are using the software are other hackers because you can’t be a corporation and count on Slackware being able to take care of you.”

So you’ve got that either/or choice: am I free or am I proprietary? Bob Young – instead of saying, “Gosh, I have to choose one or the other” – said, “I don’t like either, so what am I going to do?” He came to the insight that said, “Well the only way that big corporations, or corporations of any size, are going to trust Linux-based free software is if they’ve got a big provider because they have to make a bet on it, install servers based on that, etc. It’s a big, big investment, and that company’s got to be around and be trustworthy. So we’ve got to become the biggest. What we’re going to do, is rather than make money selling software, we’re going to make money servicing software. We’re going to put Linux up on servers everywhere around the world for downloading: design it to be downloadable for free, to become the dominant player(which they quickly did, 70% share of the market). Then they could go to corporations and say, “You want the 70 share player to take care of you. We’ll take care of you.” So he managed to build an extremely valuable company and legitimized Linux software. That was the legitimizing moment.

Big companies started to use it, and the world’s a better place for it, I would argue.

You’ve got a Red Hat Linux choice, or a Microsoft choice and operating system software for computers and servers. There you go. It was not either/or. It’s an, “I’ve got to come up with a better answer for it.” What we argue is that it comes from not saying, “Oh my God, I have proprietary free” because at that high level of abstraction, the label we put on it (like you’re conservative, you’re liberal, you’re proprietary, you’re free) makes it appear as though there is no common ground. If you look beneath it and say, “Well, how does that model work? How does this model work? Oh, we can take that piece and that piece, and put them together in a new way,” you get a better model. Is that a good enough example?

Brooke Struck: Yeah, yeah. That’s a great example.

Roger Martin: And he’s from Ancaster, Ontario. Not many people know. He’s thought of as being from Raleigh, North Carolina, because that’s where Red Hat was, but he’s a Canadian. What else does he do? He owns the Hamilton Tiger-Cats.

Brooke Struck: Oh, wow. See, you can start off with free software and end up owning the Hamilton Tiger-Cats.

Roger Martin: That is exactly the moral of this story.

Brooke Struck: Okay, so let’s dig into that a little bit deeper. Let’s focus now on the moment before this transformation of the idea, the development of the third way. Let’s focus on that moment when all you see is these two monoliths that seem to be standing across from each other. How do cognitive and social dynamics within organizations tend to reinforce that pattern of seeing the monoliths and not being able to get past it?

Roger Martin: Well, I think a bunch of these things are human: the way the human mind works, if you just want to say the absolutely basic thinking process. This is something that a great, now late, scholar named Chris Argyris talked about back in the 70s: people have a ladder of inference in their mind. People are built to make decisions. We know we have to make decisions. If we see a tiger over there, we have to decide to run or fight. We have to observe what’s around us and do something based on that. That’s just the way life works.

What Chris said is that we start at the lowest level from data, what he called directly observable data. “I see rustling in the grass over there. It might be a tiger.” Then we add inferences: “I saw rustling in the grass. It might be a tiger. Oh, that’s a problem because I’m undefended. Therefore, I better try and sneak away before the tiger sees me.” We come to a conclusion. We work our way up that ladder to a conclusion.

So, people are wired to do that. We’re not wired to say, “I saw rustling over there in the grass. I’m done here.” You’re wired to come to a conclusion, so those people and organizations who do what we’ve been describing – which is to come to these sort of Balkanized views – are just following their ladder of inference up to do the thing that they were designed evolutionarily, or by some higher power, to do.

In some sense, what I’m saying is, you have to be reflective about that ladder rather than just going vroosh, because often, once you get to the top of the ladder, you can’t even remember how you got there. I’m sure you’ve had that experience where you just know something, and somebody said, “Well, why do you think that?” You actually have to work really hard to reconstruct the pattern that got you there. Generally, you can, but it’s sort of extra work. Once you’ve got there, you’ve got there.

So what I say is, you’ve got to be more reflective about that, and I ask people to be reflective about their own model. Say, “Well, let’s specify how that model works.” Then I ask them to do a hard thing, which is, when somebody’s got a model that you think of as opposing your model, I want you to inquire into that and not ask the question like, “Boy, Brooke, that’s a pretty stupid model. Could you explain how stupid that is?” Which is actually, generally, what people are inclined to do with models they don’t like. Like, “Why on earth do you believe that? You’re not going to get anything out of that.”

Instead, say, “Brooke, that is very cool. I want to understand that better. Tell me more about how that model works. What benefits does it produce for you? For your customer?” Just, “Tell me more about that model.” It’s hard.

Another great example is the Toronto International Film Festival: Piers Handling turning it from the third best film festival in Canada to the most important film festival in the world. He loved the open, community-oriented film festival that he inherited. He hated Cannes and everything it stood for: the elites defining tastes, excluding the average person from being able to see the movies that only the elite were allowed to see.

But instead of saying, “I am going to make sure that Toronto never gets to be like that evil Cannes,” he very cleverly said, “How the heck does Cannes actually work? How does it produce benefits for the city of Cannes and South of France? How does it create benefits for the industry that it serves? How does it create benefits for the festival itself? How does that work?” On the basis of really, deeply understanding something he didn’t like at all, he figured out a model for the Toronto International Film Festival that made it the best. So the key is interrogating your own model and really understanding it, and then doing the same to a model that you just don’t love.

Brooke Struck: I like the way that you framed that. In opening the conversation, you talked about interrogating models, and you mentioned that you, yourself, try not to judge the outputs that people want from their models. Your main thing is really pushing on, helping them to dig into the models themselves.

Roger Martin: Yes.

Brooke Struck: That seems to come back around now with the story about the Toronto International Film Festival. Even looking at Cannes and saying, “I don’t value the outcomes that they value.” The inference doesn’t stand from that to, “There’s nothing interesting that I can learn about how this model works.”

Roger Martin: Right. Although, I would say that’s the inference that most people draw most of the time. You’re right, absolutely right. But sadly, most people blind themselves to that… And what he discovered is, at Cannes, they get buzz that attracts the media, that gets sponsorship to make it so we don’t have to be hand-to-mouth, begging for government money all the time. “How could we get buzz, but not in a way that they do, which is to have an elite jury be voting on what’s the Palme d’Or, the award for the best movie at the film festival? That gets everybody going, Who’s going to win? Who’s going to win? Who’s going to win? Exciting, exciting, exciting. Media buzz. How do we get that in a Toronto International Film Festival kind of way?”

There’s the insight then. It’s sort of like, “Hold it. People have to pay for tickets at TIFF. They don’t pay for tickets at Cannes. So that’s not a real audience, actually. We have real audiences. Isn’t it interesting that Toronto is both a big North American city that’s kind of like other big North American cities, and the U.S. market is the biggest film market in the world. Ah, but what’s emerging is the global market: it’s now in totality bigger than the U.S. market. It didn’t used to be. It is now.”

And, “Toronto happens to be the most global city in the world, arguably. Over 50% of GTA people have a foreign passport. 20% is the biggest for any U.S. city, in New York. So it’s unbelievably diverse from the geographic backgrounds of people. Hmm… what could we do that’s consistent with our communitarianism, and takes advantage of that? The People’s Choice Award.” So suddenly, your award is a predictor of massive successes, and it becomes the most important. It’s not the most famous. The Palme d’Or’s still probably the most famous, but there’s no question whatsoever that the most important film festival award in the world is the People’s Choice Award in Toronto.

So you figured out how that model worked and got a big a-ha that you could apply to yours, and the great thing about it – why I often use it as an example – is if you asked the question, “How community-oriented and inclusive was Toronto International Film Festival before that insight?” Let’s say the answer is an index of 100 – is this a compromise? “So we had to do something that would make it less community-oriented to get the thing we wanted?” And the answer, brilliantly, is no. Now I tell people, not only can you go to any movie you want and buy tickets to see it, you now contribute to figuring out what the future Academy Award winner is likely to be. You, just plain old Toronto Film Festival goer. So, in some sense it becomes, if anything, more inclusive than it was previously.

Brooke Struck: So, in characterizing the obstacles of business as usual, we move from not valuing the outcome that our opponents value, to dismissing how their models work. If we’re not learning from their models, we’re therefore not building better models ourselves. For years, you’ve been working on this concept of integrative thinking, which is an alternative to just accepting this kind of polarized, either/or situation. Can you tell us about the steps in the process of integrative thinking?

Roger Martin: Well, sure. One, is to both accept the models as they are, and if anything, push them to even more extremes: because compromise is, “Oh no, we’ve got to compromise,” people sort of try and come up with models that are similar. I say, “No, no, no, push them to their extremes.” When we do things where, like a big corporation was saying, “Well, should we make all of our training centralized at corporate, or regionalized? What should we do?”

and they’re already thinking about what combination of these two things. I say, “No, no, no, no. Okay, model A is: the regions do nothing. There aren’t training people in the regions. Nothing. They do zero. Nothing, and corporate head office does everything.” Then the other was, “There is no corporate training function. It’s all entirely up to the regions, not coordinated at all.” They’re like, “But we would never do either” and I say, “I don’t care. The plan is not to get one of these things. The plan is to get a better answer.” So [step] one, is push the models to their extreme.

Then it’s, “To do this, how does each model work?” So Film Festival, how does it work? Who are the stakeholders? There tend to be three, as it turns out. Most of these things are just empirical, and we’ve done hundreds and hundreds of these, it turns out. How does it work for the community? How does it work for the industry? How does it work for your entity, the festival itself? Do that for Toronto, the film industry, and TIFF. Then you do it for Cannes: the city of Cannes, the festival Cannes, and the industry there. Just lay out how it works, the mechanisms by which it works.

Now, people get confused when I tell them. They say, “What are the good things about it?” No, it’s not just that. You have to explain how it works. How does this model produce its outcome? Then, step three is, you look for integrative pathways. What we found over time is that there are three kinds of integrations. One is what we call the “hidden gem,’ where you throw away a bunch of the conflict. Bob Young did that. He said, “Oh, the conflict comes from selling software that you have to make proprietary to be able to invest in. Let’s get out of the business of selling software. Let’s talk about services.”

He threw away most of the models that created the conflict. That’s one integrative pathway. So we say, explore hidden gems. What could you toss away to build from a piece of each model? He built service: “Service is a big part of the Microsoft model. I’m going to pick service out of there. It’s a nice, big, high margin business and I’m going to pick the customizability of it from the other model. Everything else, we throw it away and we start from scratch.”

“Double down” is the second path. How can you push harder on one model to get the benefits of the other? You pushed on inclusivity with the People’s Choice Award to get the buzz that you wanted from the other model. The other one we’ve identified and see often is something called “decomposition,” where you say, “Actually, we could apply one model to part of the problem, and the other model to the other part of the problem.” It isn’t one problem, it is two problems.

An example is Connect and Develop, P&G’s famous move into a new way of doing innovation where the insight was innovation. Innovation is invention and commercialization, and we’ll use a different model for invention: getting 50% of our inventions from the outside, Connect and Develop, and double the pipeline through our commercialization machine, which is a very efficient, high-volume machine. So third is to say, “Can we find a hidden gem? Can we find a double down? Can we find a decomposition?” Usually, you can find one. In fact, I haven’t had a situation yet where we can’t find one of those. Then you’ve got to go and test it out. What I say is, anything that’s new and innovative, you need to test out, try it in little ways to see whether it works.

Brooke Struck: That’s great. I really like the kind of cognitive delay that you’re pushing there, especially around pushing the models to the extremes. Even that pushback that you noted anecdotally, that people are saying, “Well, we’re not actually interested in a model that is as extreme as we’re articulating here.” What I sense there, intuitively, is this pushback against delaying decisions, and there seems to be a bit of a kinship there with interest-based negotiation. I gather that you’re familiar with the term.

Roger Martin: Absolutely. That is trying to get beyond the position. In fact, Roger, the late Roger Fisher and Bruce Patton and Bill Ury were actually friends and colleagues of mine. “I’m pro life versus pro abortion” – don’t do that. Ask the question. What’s behind that? What are the real interests behind it, in order to be able to start to have something? That is getting beyond the labels to what’s hidden behind it.

Brooke Struck: Yeah. It seems to me that there’s a bit of a kinship there. That an interest-based negotiation, as you articulated, the idea is if you’ve got two parties sitting down at the table, and each one has already hammered out, “This is what I want the final agreement to look like,” you’ve already gone too far. You need to walk back and say, “Well, what are the priorities? What are the needs that need to be addressed by whatever final agreement is reached?”

What that final agreement looks like in order to fulfill those is, in theory, what the negotiation is supposed to be about. Again, to push on this kinship, it seems like what’s going on with integrative thinking is to delay that idea that there’s already a model in mind that we’ve chosen, and now it’s just about getting people on board with the idea that this is the right one. Instead asking, “What is it that we want to get out of these models?” and especially, “Wow do these models work?” and going through that articulation process. As I was thinking about it and reading about it, it seems a little bit like integrative thinking is, in some ways, like interest-based negotiation with yourself.

Roger Martin: Yeah. There is a kinship. I’ll tell you how far the kinship goes and where it stops. Though I understand why, I just don’t like the concept of negotiation. Integrative thinking is not negotiation. I don’t want to have the view being, “You and I have to negotiate with one another because we think differently.” “You and I have to create something magical together,” is more what I want. That’s why in my books about this – Opposable Mind, the one I wrote with the wonderful Jennifer Riel, and Creating Great Choices – why we don’t explore that kinship, because I’m kind of adverse to that aspect of negotiation.

Now, that having been said, Roger, Bill, and Bruce would say the best of “negotiators” – or people who facilitate these sessions – are the ones who can come up with creative, out-of-the-box solutions. Getting To Yes – it is like we’re disagreeing and our goal is to get these two parties to an agreement. That is not my goal, actually. My goal is to come up with a breakthrough that makes everybody better off.

Brooke Struck: Right. It’s interesting, actually, as you say that, it strikes me that perhaps the thing you’re pushing most against is the kind of adversarial nature of negotiation.

Roger Martin: Yes.

Brooke Struck: Which, in a book like Getting To Yes, seems to be the kind of deficient, and yet almost universal model of negotiation that the authors are pushing against. In fact, to really take their advice seriously, is to get past the adversarial nature of negotiation, in seemingly similar ways that there can be adversarial undertones around a boardroom. Even if everyone is “playing for the same team,” there are still factions and everyone’s got their hobby horse of an idea that they want to see pushed forward.

Roger Martin: Absolutely. I mean having BATNA play as big a role as it does, leads you in an adversarial position, right?

Brooke Struck: Yeah.

Roger Martin: I can do this negotiation, or I can default to my BATNA. I mean, I get it. Again, those guys are friends and that’s made a huge contribution. I want to make a contribution, for what it’s worth, in a somewhat different direction, which is to say if an opposing model washes up on my shores, I should look at it as manna from heaven that, in that, there are the seeds of a better answer.

I mean, we did one. It was actually Jennifer facilitating, and she’s brilliant. Jennifer Riel – my co-author, brilliant facilitator – for the senior staff at one of Canada’s finest hospitals. What they put on the table as the issue to work on, was the vaccination debate. This was years before COVID. This was more the challenge with the anti-vax movement on MMR and more straightforward vaccination then. There were administrative people, the chiefs of surgery, and it was a children’s hospital, so pediatrics and nurses, et cetera. One of the surgeons said – when Jennifer put this on the table – “There is no vax debate.”

He was objecting to actually using this as an example, and that’s classically what happens. “There is no debate. The science has been determined.”

Brooke Struck: We’ve talked about this process of pushing models to their extremes, really interrogating them to see how they work. You noted three paths to combining elements, or finding different options to move forward with. The pick-and-choose model, taking one element from each, doubling down on one model in some way to get a benefit that the other typically produces, and then the decomposition. Then finally, taking one permutation that comes out of each of these three pathways, and testing them out, and iterating before you scale.

Roger Martin: You got it.

Brooke Struck: It’s almost like I read the book, Roger.

Roger Martin: Yeah, it’s suspiciously like that.

Brooke Struck: How do these steps overcome the cognitive and social barriers that we’ve been talking about within organizations that typically lead to the facing world?

Roger Martin: The key that I found is to just make it playful. To say, “Why don’t we just play around with this for a while?” and that’s what we had to do with the vax thing. In that case, it was, “Okay, you may say the science is settled, but vaccination rates, at least in the U.S., are going down. So, is it settled? Is this issue settled?” And they were like, “Well, I guess not in that sense. But we know the right answer.” And I said, “Yeah… But why don’t we just play with this for a little? Let’s just suspend disbelief for a moment and say, how does the public health, pro-vaccination model work? And how does the anti-vax model work?”

What they came to, is the role of free will and choice, and how the way it was being handled at that point, is that it was exacerbating the sense of free choice. I think they came to a better view as to, if we actually want to tackle this, we’ve got to understand how people who are sensitive to the question of, “Do I have free voice in my children’s medical care?” – how we’ve got to approach them to have a chance of this working.

In that case, it was a little bit of something I often do. It’s, “Let’s just play. How bad can this be?” Now, the answer of how bad this can be is often, essentially, a terrification of: “If I start thinking about it, maybe I will be seduced by the other side.” Or, “By even having this conversation, I’m legitimizing the anti-vax movement.” So that’s why I say let’s just play. Let’s just play and see if there’s anything good that comes out of this.

I say the same about strategy and about innovation. If you get too serious too fast, everybody just clams up and can’t think past their own nose. If they’re in a playful mood, they can. It’s like getting somewhat back into a childish state.

Brooke Struck: Yeah. I will note in passing, for interested listeners and readers, that Roger’s done some really interesting work with high-school-age children, and I think even elementary-school-age children.

Roger Martin: Yes.

Brooke Struck: So I would encourage interested listeners and readers to go and hunt that down, because it really is very cool.

Roger Martin: Yes. It’s an initiative called I-Think, and if you just go on and look for Rotman I-Think, you’ll be able to find stuff on that.

Brooke Struck: As the father of a young child, I’ve really enjoyed going down the rabbit hole of that. But I wanted to come back to this idea of compromise. One of the things you said in opening our conversation, is that you really don’t like compromise.

Roger Martin: No.

Brooke Struck: Now that we’ve gone through a discussion of how the typical discursive dynamics tend to lead to these facing worlds, and how we can do it a little bit differently, how can we come back to this idea of compromise? How have we rehabilitated it? What is the sense of positive compromise, if such a thing exists, and do you have a word for it that you prefer, so that we can get away from this thing that everybody seems to summarily hate?

Roger Martin: Well, I don’t use “compromise” or “negotiation.” I’m looking for possibilities. Generally speaking, I just won’t stop until I get a better idea. I mean, this happened at the Rotman School when I showed up as Dean. For those who know my background, I was a business guy, not an academic, not a PhD. Being a dean was my first job in an academic institution ever, and I arrived and was told by the faculty, “You have to decide, Roger.” They were deeply suspicious of me because I went to Harvard Business School, which is sort of the “great Satan” for the research-oriented business school, even though Harvard Business School does more research than any other business school. But they’re viewed as teaching-oriented.

So it was, “Are you going to be teaching-oriented? Are you going to make Rotman into a teaching-oriented school or a research-oriented school?” They said, “You’ve got to choose,” and they described, “Well, if you’re teaching-oriented, yes, students might like it, but you’ll never be able to hire good faculty. We’ll never be any good. If you’re research-oriented, you’re going to have to live with the fact that students aren’t going to like it very much, but you can build a great research faculty, and that’ll make you a great school.”

So they had their own idea of which my answer should be, and I just said, “I gave up a really, really good job and a really, really good career to do public service back in my home country. Am I literally getting a start with saying, ‘Well, I want to be somewhat more teaching-oriented?'” “Shoot me now,” was kind of my reaction, so I thought about it until I came up with an integrative solution, and the integrative solution was one that both absolutely skyrocketed our teaching ratings and took us from nowhere in research to being ranked.

I know it’s hard to believe, but [we’re] being ranked third in the business school world in research, behind only Harvard and Wharton, ahead of Stanford, Sloan, Columbia, Chicago, Duke, Berkeley. Like unthinkable. Literally, unthinkable. Because I wasn’t willing to even contemplate compromise, we were going to be better than anybody in the entire faculty could ever believe we would be in research. Way better. Not better. Way, way, way better, and better at teaching than anybody could contemplate. And that’s doable. So I eat my own dog food. I do it wherever I go because life is too short for compromise.

Brooke Struck: I like that, and shifting now into the practical aspects of this. You note in the book that integrative thinking is both a solo, as well as a team sport.

Roger Martin: Yep.

Brooke Struck: I think a lot of what we’ve talked about here already gives some of the ingredients of how individuals can get started on this. The book, Creating Great Choices, has lots more detail and great examples to help people work through that. But for those wanting to engage in a team sport, working in a group environment and wanting to bring this kind of practice into what it is that they’re doing, where can they start? What can they do Monday morning to get the ball rolling, to change the kinds of conversations they’re having in their organizations?

Roger Martin: Well, I would say don’t go looking for trouble, but if trouble finds you -which is you want to do X, and the other person wants to do not X – I would literally start by saying, “Hey, can we try something here? I’d like to understand, fully, your model. How your model works, how it produces the outputs that you see it producing, and I’ll do the same for mine. I’d love to start with yours because, here’s what I want to demonstrate by working on yours, is that I’m not trying to tear it down. I’m trying to understand it, so I’m going to be exceedingly positive about your model with the hopes that you will be about mine.”

“Then, what I’d love to do is work together to see – can we get the key attributes of both of these models in one new model? Can we just try that? We won’t do it for more than an hour. We’ll take a break. If you’re tired, disgusted, annoyed by that time, we won’t do anything more, but we’ll continue if you’re saying, ‘Oh man, we’re making some progress here and we might be able to come up with something.’ Would that be okay with you? Would that be a use of an hour that you could imagine enjoying and having some good come from?” And hopefully, the other person will say yes.

My experience is they virtually always say yes. Then the key is to be positive about their model. Say, “Oh, I don’t know. That, no. No, no, no, no, no. That’s not … Oh, you think that?” Don’t do anything like that. Say, “Okay, so the idea here is for the consumers – they would get this and that, and that’s a real benefit. Did I do that right? And for the company, this is what it does for it. And for our employees, this is what it does. Do I have that? So all of that together gets you that. Do I have that right?” You just are unfailingly kind of non-judgmental about it. You’re just seeking to understand.

Don’t try to do anything towards a creative solution until you get yours out, too. Then say, “We’re going to turn to mine.” Then after you’ve got the two, say, “Hey, so here’s what I’d love to do. I’d love to ask the question, “Here’s how these work – what are the things we absolutely love, love, love? What are the pieces of these we love?” And create the love chart with little hearts on it. “Here’s things we love,” and then say, “Okay, now we try to find a way to get those things in a brand new model.” generally, you can come up with a brand new model, and it’s not super, super hard. I mean, people should do it all the time, they just don’t, and they’re trained not to. They’re trained to fight and negotiate, not do that.

Brooke Struck: Yeah, so moving a little bit in reverse order, what we talked about at the beginning of the conversation is the steps to go through, like “Here’s the recipe.” What you’ve just laid out here is, “Here’s how to create an opening with someone to get those steps going” and the furthest step back – and this resonates with something from Creating Great Choices as well – is that you note that mindset, even personality, or even way of being in the world, seems to be an important ingredient here. It’s not just about knowing the process and having the skills. It’s about your approach, and from the way that you describe it, your respect for other people. That you need to be able to truly believe and embrace the idea that a reasonable person can hold a different view.

Roger Martin: Yes, which has now disappeared in America.

Brooke Struck: Well, I mean, I know you’re down in the States now. But as a Canadian, you must know that we’re not that far off up here either.

Roger Martin: No. But yeah, the view is, if you see things differently, it’s because you’re stupid or evil. That’s the two explanations.

Brooke Struck: Yeah.

Roger Martin: People say, “Well, that’s pretty harsh, Roger. Well, they’re just variants of stupid. They don’t get it. They don’t really understand. They haven’t thought it through. That’s all variants of stupid, or they’re just meanies. They don’t care about these people and they’re evil.” So yeah, if you have a mindset that says opposing ideas are the product of stupid or evil people, you’ll be stuck, unfortunately, having a relatively miserable life. I mean, I hate to put too fine a point on it, but that’s the long and short of it. You will be stuck having a miserable life.

If instead, you can get yourself to the point of view of saying, “I have a view worth hearing, but I might be missing something,” then you’ll have a much happier life, because what you’ll be inclined to do is put out your view to others with a signaling of, “This is what I’ve thought of thus far. But this is the best answer I could come up with thus far.” And then if you’ve got the, “But I might be missing something,” then it’s just this very, very open and genuine invitation for them to show you what you might be missing. It’s just this invitation.

People would say, “Roger, it’s because you don’t understand about leaders. Leaders can’t be that vulnerable.” Which is, again, a model. I talked about models. That’s a model. Leaders aren’t vulnerable, and it’s one of those interesting, kind of fallacious models, where if you just look at leaders and how vulnerability actually works – the leaders that show vulnerability of that sort are the most beloved leaders and are the ones that people would run through a brick wall to help. But as long as you have the view that that’s vulnerable, it’s just not, and the best, best leaders I’ve ever worked with, of giant corporations in the public sector, all have that kind of vulnerability.

I’ll always remember, way back when, a guy who runs a $100-billion-plus private company, one of the richest people in the world – we were sitting. We were doing a study for his company and he rarely used four-letter words. And in this meeting, he described a practice that they’d had, and it was a well thought-out practice. It was in a commodities business, and it built up stores of this commodity at a certain cycle of the year because it felt that that was better,and everybody knew that he was intimately involved and this wasn’t somebody else’s idea. It was at least his idea as much as anybody else, and he just says, “We’ve got to look at this and say after 10 years of doing this, this aint worth a-” four-letter word that starts with D.

And everybody was surprised because he didn’t swear, and that’s not a terrible sort of word. But did people think he’s less of a CEO? No, they were like, “Holy smokes. He’s willing to look at his own ideas and say some of them just aren’t so hot. I guess I can do that too, and that’s the kind of place we have around here, where you don’t get shot for admitting that you had an idea that was bad. In fact, this guy just did it of his own volition. Boy, he must be committed to learning and getting better answers.” Whereas somebody might go, “Well, he was very vulnerable there, and you can’t be vulnerable and be a leader.” He was more leaderly after he did it in the eyes of his followers, than he was before it.

Brooke Struck: Right.

Roger Martin: Now, if he was wrong 90% of the time, they would say, “Hey, we’ve got a bit of a problem here,” but you wouldn’t be a leader. So that’s the stance. If you want to be successful in life, you should try to convince yourself to always go forward with the, “I have a view worth hearing, but I might be missing something.”

Brooke Struck: I really like that, and I think that that’s a great note to tie things up on, coming back to the idea that taking that kind of stance is not to flip-flop, it’s not to compromise, it’s not to try and please everybody. But that stance is a necessary starting point to really do well. All of the stuff that gets built on top that we’ve been discussing for the past hour, about figuring out what it is that you might be missing, the partial picture that other people who disagree with you are carrying around, and how it is that you can bring together the best of those two partial pictures into something that’s more complete than either one on its own.

Roger Martin: Yeah, you got it. That is it. You see, in that little description, to me, there was no hint of either compromise or negotiation. I think you can accomplish all those things without ever delving into those two rhetorical realms.

Brooke Struck: Yeah. Yeah, I really like that. Anyway, Roger, thank you very much for this discussion. It’s been great.

Roger Martin: You’re welcome, and it was my pleasure. It’s always fun to talk to somebody who’s read the book and has interesting thoughts about it. So thank you for that.

We want to hear from you! If you are enjoying these podcasts, please let us know. Email our editor with your comments, suggestions, recommendations, and thoughts about the discussion.