How Facebook Increased The Number Of Votes In The 2010 US Congressional Elections

Imagine you open your Facebook page and see a fundraising program for koalas burnt in the Australian bushfires. You see that Sarah (your best friend), Tom (your neighbor), and John (your friend’s colleague) have already donated to the cause. You click the link to donate and announce your participation by pressing the button so that everyone knows you support the same cause. Had you financially planned for that donation in advance? Probably not, but you like Sarah, so if she did it, maybe you should too.

Background

This hallmark study,1 which sought to investigate if social media can increase voter turnout, was performed in the US in 2010 and published in 2012 in the prestigious journal Nature. It has since been mentioned more than 50 times in different blogs and news sites, including The Guardian. Despite the widely-held belief that online mobilization played a significant role in recent elections,2 the results of a meta-analysis study on email experiments indicate that online methods are ineffective for influencing voter behavior.3 What makes social media so attractive to researchers is the possibility of reaching large populations that it brings; even an increase in the number of voters as small as 1% can be substantial given a large enough population of users.

Behavioral Science, Democratized

We make 35,000 decisions each day, often in environments that aren’t conducive to making sound choices.

At TDL, we work with organizations in the public and private sectors—from new startups, to governments, to established players like the Gates Foundation—to debias decision-making and create better outcomes for everyone.

Methodology

To verify the hypothesis that voter turnout can be increased with the help of an online social network, the researchers randomly chose about 61 million eligible voters who had access to Facebook on November 2nd, 2010, the day of US congressional elections. Individuals were randomly assigned to either a control group, a social message group, or an informational group, and the actual voting rate was collected for the individuals who participated in this study using public voting records.

Results

The social message group, in which individuals saw their friends’ faces randomly, pressed the “I Voted” button about 3% more than the information group. This indicates that merely seeing familiar faces can impact an individual’s voting behavior. This group also clicked on the link that provided information on where to vote 0.26% more than the information group, suggesting that seeing familiar faces has a small yet positive impact on information-seeking behaviors.

In terms of real votes, the social message group voted 0.39% more than the control group, suggesting that seeing the faces of friends can contribute to an increase in real-world voting. Interestingly, the number of real-world votes for the social message group was the same as that of the information group, suggesting that seeing pictures of friends isn’t enough to increase real-world voting in and of itself, even though this increased the number of people who said they voted.

In terms of real votes, the social message group voted 0.39% more than the control group, suggesting that seeing the faces of friends can contribute to an increase in real-world voting. Interestingly, the number of real-world votes for the social message group was the same as that of the information group, suggesting that seeing pictures of friends isn’t enough to increase real-world voting in and of itself, even though this increased the number of people who said they voted.

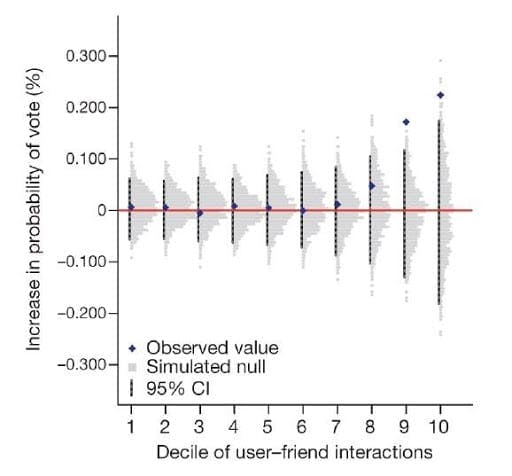

To better identify the contagion (i.e., the indirect effects that spread from a person to another because of being friends), the researchers used the number of Facebook interactions between each pair of friends as a proxy for their closeness. Therefore, the researchers could test whether the closeness of friendships can change the voting behavior of individuals. The results showed that the probability of voting increases in individuals whose close friends had voted.

Close friends affect an individual’s voting behavior. As the level of interaction increases, so does the effect of a friend’s voting behavior on an individual’s voting.

The results of this study demonstrate that while friendships increased political self-expression (i.e., the act of saying that you’re voting), close friendships—although they make up only 7% of Facebook friendships—accounted for a significant increase in real voting. It has been estimated that Facebook social messages increased the number of votes directly by about 60,000 votes and indirectly (i.e., through social contagion) by another 280,000 votes.

The AI Governance Challenge

Results

The results of this study are apparent; however, there have been concerns about potential privacy violations and the ethics behind web-based experiments.4 This study showed that online political mobilization increases political self-expression as well as real voter turnout. But these results go beyond this context and point to the importance of social approval on behavioral change. It should be noted that the indirect effect of the message was about four times more potent than the direct effects, highlighting the influence of social networks in society and their ability to change individuals’ behavior.

Harnessing the social approval effect in real-life

Policymakers could leverage the social approval effect to drive change in many different areas, including:

- Social media. Social media may provide political decision-makers with a cheap, large-scale method of impacting individuals’ behavior both directly and indirectly. As an example, sending a message on social media about receiving a vaccination and referencing users’ friends who have gotten the vaccine (i.e., showing their profile pictures) could increase the vaccination rate.

- Public health. The social approval effect could be leveraged by encouraging individuals who are willing to wear a mask when in public places to post a photo on their social media accounts. This, in turn, could encourage their direct and indirect friends to wear masks as well.

- Energy conservation. The social approval effect could encourage a reduction in energy waste. Simply knowing your neighbor’s level of energy consumption could affect your behavior enough to reduce your consumption, shown by the pilot study that OPOWER, a US-based software company, performed in partnership with the utility providers of several American states.5

Takeaways

The efficiency of the social approval effect can be explained by the concept of conditional cooperation, which means that people are more prone to participate in an act of public good — such as receiving a vaccination, wearing masks in public places or consuming less energy — if they see that other people are doing the same. Merely seeing that others are acting in a certain way can indeed have a profound impact on our choices.

References

- Bond, R. M., Fariss, C. J., Jones, J. J., Kramer, A. D., Marlow, C., Settle, J. E., & Fowler, J. H. (2012). A 61-million-person experiment in social influence and political mobilization. Nature, 489(7415), 295-298.

- Christakis, N. A., & Fowler, J. H. (2009). Connected: The surprising power of our social networks and how they shape our lives. Little, Brown Spark.

- Huckfeldt, R. R., & Sprague, J. (1995). Citizens, politics and social communication: Information and influence in an election campaign. Cambridge University Press.

- Criticism of Facebook. (Last modified Feb 29, 2020). In Wikipedia. Retrieved March 25, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/?curid=12878216

- Allcott, Hunt. (2011). “Social Norms and Energy Conservation.” Journal of Public Economics 95: 1082-1095.

About the Author

Maral Yeganeh

Maral Yeganeh Doost had finished her Ph.D. in neuroscience and currently, she is a post-doctoral fellow at Montreal Neurological Institute of Mcgill University. Her research is about motivation and its role in human actions in both healthy and stroke survivors. Her studies aim to quantify the extent of incentive effect on the performance of behavioral tasks. Maral is interested in harnessing the principles of behavioral economics in public policy to improve public health among Canadians.