Why do we prefer doing something to doing nothing?

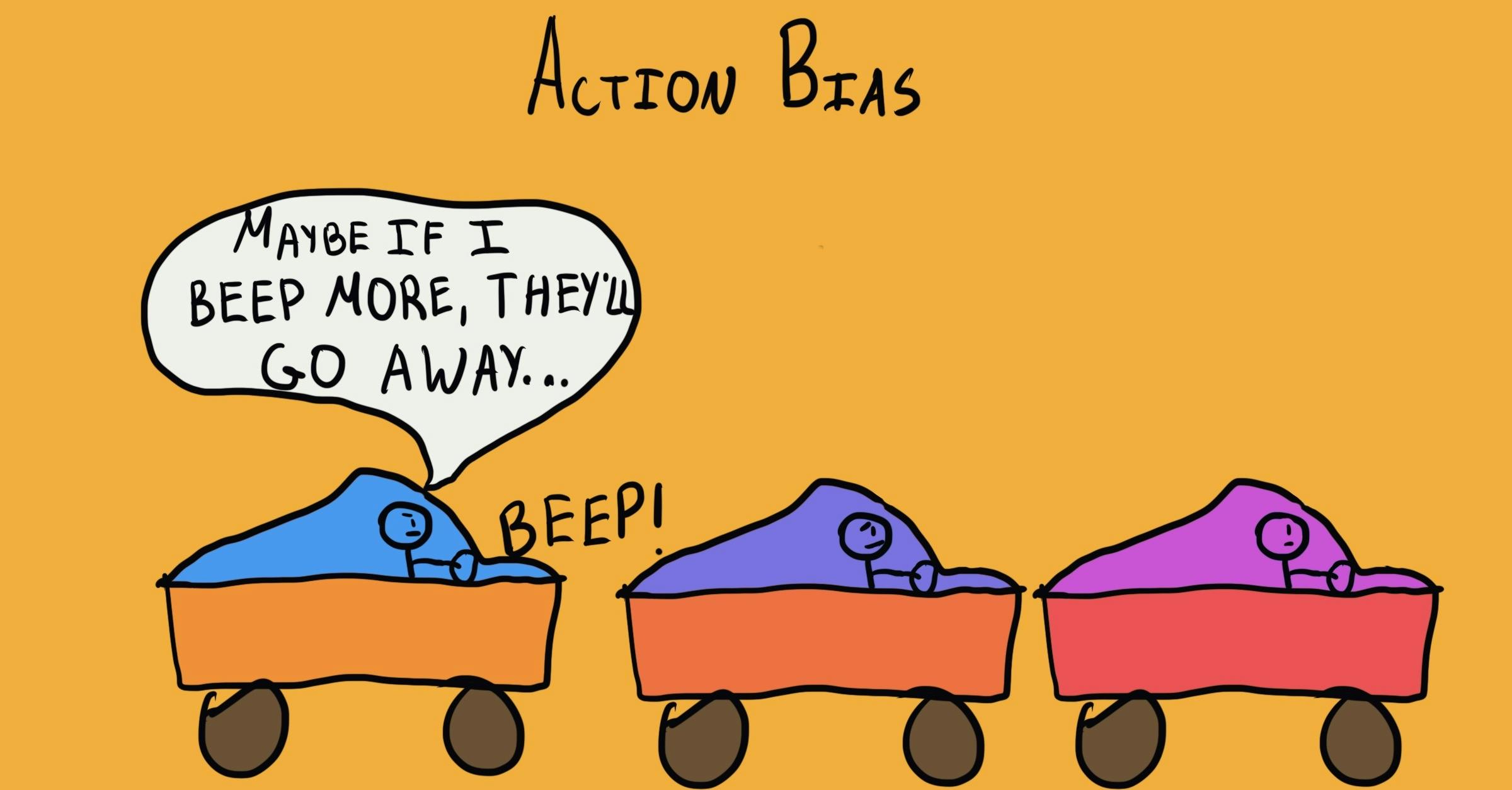

Action Bias

, explained.What is the Action Bias?

The action bias describes our tendency to favor action over inaction, often to our benefit. However, there are times when we feel compelled to act, even if there’s no evidence that it will lead to a better outcome than doing nothing would. Our tendency to respond with action as a default, automatic reaction, even without solid rationale to support it, has been termed the action bias.

Where this bias occurs

Suppose you’re a soccer goalkeeper, preparing to block a penalty kick in the midst of the final playoff game. If you’re like most goalies, when attempting to stop a shot, you’ll jump either to the left or right nearly every time. Yet your chances of successfully blocking the kick are statistically greater if you simply stay still.1

So what compels you to jump instead of standing your ground? It’s the action bias: our instinct that doing something is better than doing nothing. You may feel that people would judge your failure to make the save less harshly if you could prove that you made an attempt to stop it. Unfortunately, as counterintuitive as it feels it’s often inaction that increases your odds of success.

Debias Your Organization

Most of us work & live in environments that aren’t optimized for solid decision-making. We work with organizations of all kinds to identify sources of cognitive bias & develop tailored solutions.

Individual effects

Prioritizing action over inaction, without sufficient reasoning to support it, can lead us to mishandle a situation. It’s an automatic response based upon impulse instead of logic. If we make a decision without considering all possible information, the action bias can lead us down a less effective route, compromising our outcome.

Systemic effects

In our society, the action bias propagates the belief that those who fail to act are to blame. Even if acting doesn’t pan out as we’d hoped, we can rationalize that it would have been worse if we’d done nothing (even if this isn’t the case). This rationale reinforces our view of action as superior to inaction, creating an endless cycle of poor decisions.

In the earliest paper on the action bias, Anthony Patt and Richard Zeckhauser proposed that a systematic challenge we face from taking unnecessary action is in policy-making.2 They described how in order to make a salient impression, politicians will often pass showy—but relatively ineffective—environmental regulations. Such legislative action gives the impression that something is being done, when in actuality, the effects are minimal. Our bias towards action may result in us applauding these empty actions, even though the politician is making no real progress.

How it affects product

The action bias may cause us to overcompensate when experiencing technical difficulties. Rather than patiently waiting for these issues to fix themselves (as they so often do), we try to do anything to speed up the process. However, our desperate efforts are often to no avail—if anything, they might worsen the problem.

This happens every day in our online use. When a website takes too long, we repeatedly reload the page. Or when an app is too slow, we will close out of it hundreds of times. Although waiting is annoying when we are accustomed to instant gratification, sometimes it is the only solution for our internet issues.

The action bias even extends to how we try to fix our devices. Let’s say you spill a glass of water on your laptop, which is closed and shut off on the kitchen counter. What is your first instinct? Probably frantically pressing the on button to ensure your laptop still works. Little do we realize that turning the computer on only causes the water to get deeper into the circuitry, substantially increasing the damage. Instead, the best solution is to wait for the laptop to fully dry by placing it in a bag of rice or in front of a fan. The drier the laptop, the better—which means the longer you hold off on action, the better.

Next time you are experiencing technical difficulties, remember this: sometimes less is more. Give your computer or phone time to sort itself before moving onto the next step.

The action bias and AI

With all of these new developments in AI, we are eager to incorporate this new technology into everything we do. After all, automation equals optimization, right? As it turns out, this might not always be the case, especially when we ask AI to perform what would otherwise be easy tasks.

Imagine you get home from work and want to turn on the lights. The simplest solution is to flick the light switch beside the door—so simple, in fact, it essentially equates to inaction. However, excited about the new smart home device you installed, you ask an AI assistant to do this instead. By incorporating this additional step, you cause exponentially more environmental damage (remember that training a single AI system can release up to 25,000 pounds of carbon dioxide).8 This is not to say we shouldn’t use AI. But if we can do something ourselves with a simple action, then we should opt for it.

Why it happens

“The devil makes work for idle hands” is an old expression emphasizing that staying busy will keep you out of trouble. It’s just one example of how we consider a lack of action to be inherently wrong. Such misconceptions predate the development of the action bias by centuries. Although this bias is nothing new, we have only recently begun studying its effects. Thus, there are many things that we still don’t fully understand about it. Despite these limitations, researchers have found some evidence of what causes the action bias.

Is it learned or innate?

Thousands of years ago, immediate action was required for our evolutionary ancestors to survive. Our tendency towards action is something hardwired into us from our history as hunter-gatherers.3

This automatic impulse was once incredibly adaptive. But in our modern society, the action bias is less necessary for survival than it once was. That being said, those who act are still rewarded above those who do not. For example, students who participate in class are often praised above those who choose to remain quiet. This reinforces our instinct to act, causing us to engage in this behavior more, thereby making it habitual. Unfortunately, this makes us more likely to respond with action in situations better suited to inaction—such as raising our hands when we don’t know the answer to the teacher’s question.

Not only does rewarding action propagate this bias, but so does punishing inaction. Research shows that people with negative past experiences from failing to act are more likely to engage in the action bias.4 Our regret mobilizes us to do something to avoid another failure. Unfortunately, this can backfire if we find ourselves biased towards action in a situation where the best response is doing nothing.

To sum it all up, while it’s likely the action bias originates from human survival, these instincts are strengthened by learning patterns of reinforcement and punishment in our everyday lives.

The action bias and our sense of control

Our need for action also stems from our need for control. Activity makes us feel as though we have the capacity to change things, while passivity makes us feel like we’ve given up and have accepted that we can do nothing more. Essentially, doing something makes us feel better about ourselves than not doing something, reinforcing this behavior.

Furthermore, our overconfidence may encourage us to make unnecessary or even harmful decisions. Sometimes we take action because we feel as though we have significant control over the outcome, even when that outcome is completely random.

Consider the financial market, where overconfidence causes people to trade frequently, as they’re certain that their decisions will lead to lucrative outcomes. Specifically, this tends to occur in uncertain situations when people attempt to predict which stocks will rise or fall. Their confidence in their ability to make such predictions incites them into action. Granted, action may lead to big gains, but oftentimes traders learn the hard way that things would have been better if they never invested in the first place.5

Why it is important

We equate keeping busy with productivity, another quality we assign significant value to. However, a lack of action often proves to be more productive than taking action.

Imagine being in bumper-to-bumper traffic on a highway. You might find yourself frustrated that you’re moving at a snail’s pace, and consider getting off at the next exit to take back roads to your destination. This could wind up taking even longer than staying on the busy highway, and could cause you to use more gas.

While logic tells us that staying on the highway is more efficient, we feel that getting off is the more efficient decision. This is because when sitting in traffic, we feel like we’re getting nowhere, while on the other route we’re able to drive at a reasonable speed. Here, taking action is actually less productive than deciding to stay put, even if it doesn’t feel that way.

Being aware of the action bias increases our productivity by helping us make decisions based on the most efficient solution, even if that solution is doing nothing. The action bias can cloud our judgements, but if we are cognizant of its effects, we can work to overcome it. This allows us to evaluate situations more effectively and recognize when we misplace our impulse to act.

How to avoid it

Choosing inaction over action doesn’t mean giving up. As a matter of fact, it’s frequently more admirable to do so. Consequently, we should avoid taking unnecessary action so that it doesn’t become our default response. Deliberately deciding to do nothing is a good practice in being patient which can be challenging to master. Self-control is a skill that needs to be cultivated, and the more we work on it, the stronger it gets.

Learning to avoid the action bias is a long-term process that involves going against ingrained impulses and predispositions. Unless the situation demands immediate action, it’s often better to take a step back and evaluate the pros and cons of each possible response.

Referring back to the example of being stuck in traffic, instead of becoming frustrated and getting off the highway at the first possible exit, sit for a moment to rationalize your situation. Taking time to think through the consequences of action versus inaction can help you either support or negate your initial urge to act.

Remember, the goal here is not to eliminate action as a response altogether. The point is to give equal consideration to inaction as a possible response, rather than automatically resorting to action. Doing so will allow for more effective decision-making and more profitable outcomes.

How it all started

Patt and Zeckhauser pioneered the theoretical and empirical exploration of the action bias in 2000.6 Their paper defined the action bias as “a penchant for action [that is] a product of nonrational behavior.” They were some of the first to suggest that our proclivity for action is a heuristic or a shortcut that can unfortunately lead to poor decision-making in a variety of circumstances.

Importantly, Patt and Zechauser proposed three reasons for why the action bias might occur. The first is due to evolutionary and experiential reinforcements, which have led us to view action as a means to survival. Additionally, they suggested that we engage in action in hopes of some recognition or reward. Finally, they supposed that taking action helps us to learn about a situation to help us learn how to respond if we encounter similar ones in the future.

Example 1 – Difficult diagnoses

The action bias regularly manifests in the health sector, specifically when it comes to treating patients with unusual symptom presentations that don't seem to require urgent care. If there’s no clear diagnosis, the majority of doctors prefer to run tests in attempts to find the root of the problem, rather than schedule a follow-up to see if symptoms have changed.7

This is an example of the action bias, as these patients don’t present with symptoms that require emergency treatment. It would be less costly and less time consuming to schedule a follow-up appointment than it would be to run a full workup, yet doctors tend towards the latter. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, in fact, many patients likely appreciate having their concerns validated in such a way. Regardless, this is still exemplary of the action bias, as it demonstrates a preference for action over inaction in the absence of a true rationale for doing so.

Example 2 – Investing

There is an abundance of action bias examples in the realm of investments. As mentioned previously, overconfidence and a desire for control are both leading causes of the action bias. Excessive certainty in one’s ability to make good financial decisions can lead to over-trading. Similarly, a desire to maintain control over your investments might lead you to trade more frequently than you should. However, self-control often makes for a far better strategy, and patience pays off where over-trading doesn’t.

Panic can also lead us to resort to the action bias. Checking your portfolio regularly is a maintenance factor for the action bias, as it brings all changes to your attention. Upon noticing a slight dip in value, you may rashly decide to sell before matters worsen. Often, these drops in value are only temporary, and things right themselves on their own. While taking action might feel like the best form of damage control, it can cost you in the long-term.

Summary

What it is

The action bias is our automatic tendency to take action, even when the better choice may be holding off on doing anything at all.

Why it happens

The action bias was once evolutionarily adaptive, becoming hardwired in us as a means of survival. Patterns of reinforcement and punishments cause us to continue engaging in this behavior.

Other factors contribute to sustaining the action bias, including prior experiences where inaction caused us to fail. Additionally, overconfidence in our ability to predict a favorable outcome and our desire to feel in control over our circumstances both lead us to unnecessarily act.

Example 1 - Difficult diagnoses

When meeting with a patient who presents with unusual symptoms that are difficult to diagnose, but don’t seem to be posing any immediate threat to their wellbeing, doctors tend to engage in the action bias by choosing to run a full workup, rather than scheduling a follow-up appointment.

Example 2 - Investing

Factors such as panic, overconfidence, and a desire for control can lead us to make poor decisions when it comes to our investments, such as over-trading or selling low. These decisions result from the action bias, as we feel compelled to do something, instead of patiently working towards a future goal.

How to avoid it

Avoiding the action bias requires us to unlearn our impulse to respond with action in ambiguous situations. Instead of reacting automatically, we should consider the consequences of both action and inaction and compare their effectiveness. Doing so permits us to engage in more informed decision-making.

Related TDL articles

Why do we anticipate regret before we make a decision?

We often take action because we are afraid of what will happen if we don’t take action. This is called regret aversion: where we do something to mitigate our future guilt of not doing something. Read this article to learn more about what regret aversion is, why it happens, and how we can avoid it.

Why don't we pull the trolley lever?

Just as we prefer action over inaction, we also react more strongly to action than inaction. This is especially true when doing something accidentally leads to harmful consequences—even if not acting would have led to similarly disastrous results. This is called the omission bias. Read this article to learn how the action bias connects to the omission bias and how we can work against both of these impulses.