Iterative Design

The Basic Idea

You’re on a quest to design the perfect brownie recipe for your food blog. After hours of online research, reviewing cookbook after cookbook, you come up with a prototype. You bake it, taste it, and share your creation with your friends. You ask for their feedback and a major note is that the texture is not quite right. It’s far too cakey and not fudgy enough. It’s back to the drawing board. You rework the recipe and present the updated version. The good news is that they loved the consistency, but a lot of them mentioned that the baked goods were too sweet. You return to the kitchen to make the final few adjustments, and you think you’ve hit a home run. Your friends take one bite in and all you hear is compliments. That’s it, you managed to develop the best brownie recipe. Time to share it with everyone!

This process of gradually refining a brownie recipe is a simple example of an established form of design methodology known as iterative design. The cyclical process of iterative design focuses on making incremental progress towards the final product. Each iteration builds upon the previous one, gradually refining the design based on user feedback and testing results.

Rather than attempting to design the perfect product in one go, designers first start with a prototypical, or basic version, of the product. The insights gathered from product testing are used to inform the design team of any necessary changes or improvements. Designers repeat prototyping, testing, analyzing, and refining until the product reaches the desired level of quality and functionality.1 It’s a common technique that can be applied to various industries, particularly prominent in the world of user experience (UX), human-computer interaction (HCI), and digital product.

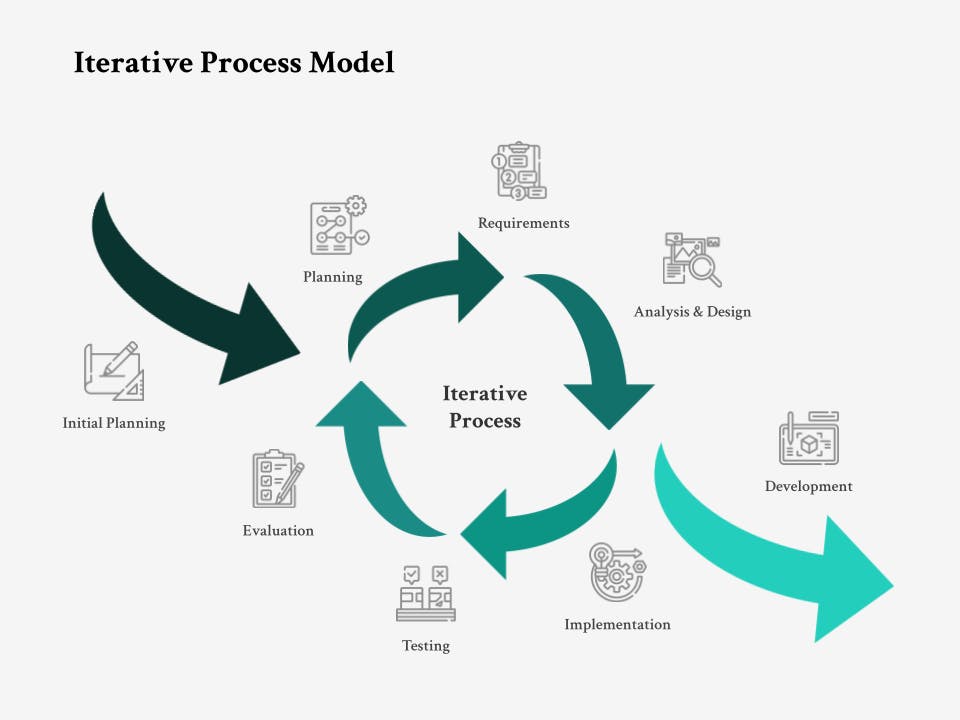

The iterative design cycle consists of 4 key phases:2

1. Identifying the Problem and Research: Design teams outline the issues they would like to solve (for the initial prototype or in subsequent iterations). They consult the literature and reference relevant product feedback.

2. Developing Ideas and Solutions: Designers engage in brainstorming sessions, drawing up diagrams and creating design specifications. A version of the product is developed based on the proposed design specification. Prototyping is crucial as it provides a tangible version of the product for internal review and quick user feedback, even before formal testing.

3. Testing the Solution: The version gets tested on users and feedback is gathered. This phase assesses beyond usability to include other key metrics like engagement, efficiency, and error rate, depending on the product goals.

4. Evaluating the Solution: Evaluation should lead directly to the decision-making process on what the next steps are: whether to iterate further based on feedback, pivot the design concept entirely, or move towards finalization. This phase includes prioritizing feedback and determining the scope of the next iteration.

Image Source: What Is Iterative Design? Radiant Digital (2021)

Iterative design is closely linked to another method known as incremental development. Despite their fundamental differences, the terms are often lumped together or used interchangeably. Where do they differ? Incremental development focuses on adding a new feature to the design one by one until a complete product is reached—like ascending a staircase. Conversely, the iterative design process is based on a cyclical pattern that involves constant refinement and testing before deciding on a final version of the product.

At the heart of the iterative design process is testing.3 Testing is a precious tool for those striving to improve their product, it involves asking critical questions, getting feedback from others, and conducting research to identify gaps that can be filled in future iterations of the product. In a nutshell, the purpose of the iterative design process is to end up with the best possible version of the product.

Great design is the iteration of a good design.

M. Cobanli, the founder of OMC Design Studios

About the Author

Samantha Lau

Samantha graduated from the University of Toronto, majoring in psychology and criminology. During her undergraduate degree, she studied how mindfulness meditation impacted human memory which sparked her interest in cognition. Samantha is curious about the way behavioural science impacts design, particularly in the UX field. As she works to make behavioural science more accessible with The Decision Lab, she is preparing to start her Master of Behavioural and Decision Sciences degree at the University of Pennsylvania. In her free time, you can catch her at a concert or in a dance studio.