Why do we prefer things that we are familiar with?

Mere Exposure Effect

, explained.What is the Mere Exposure Effect?

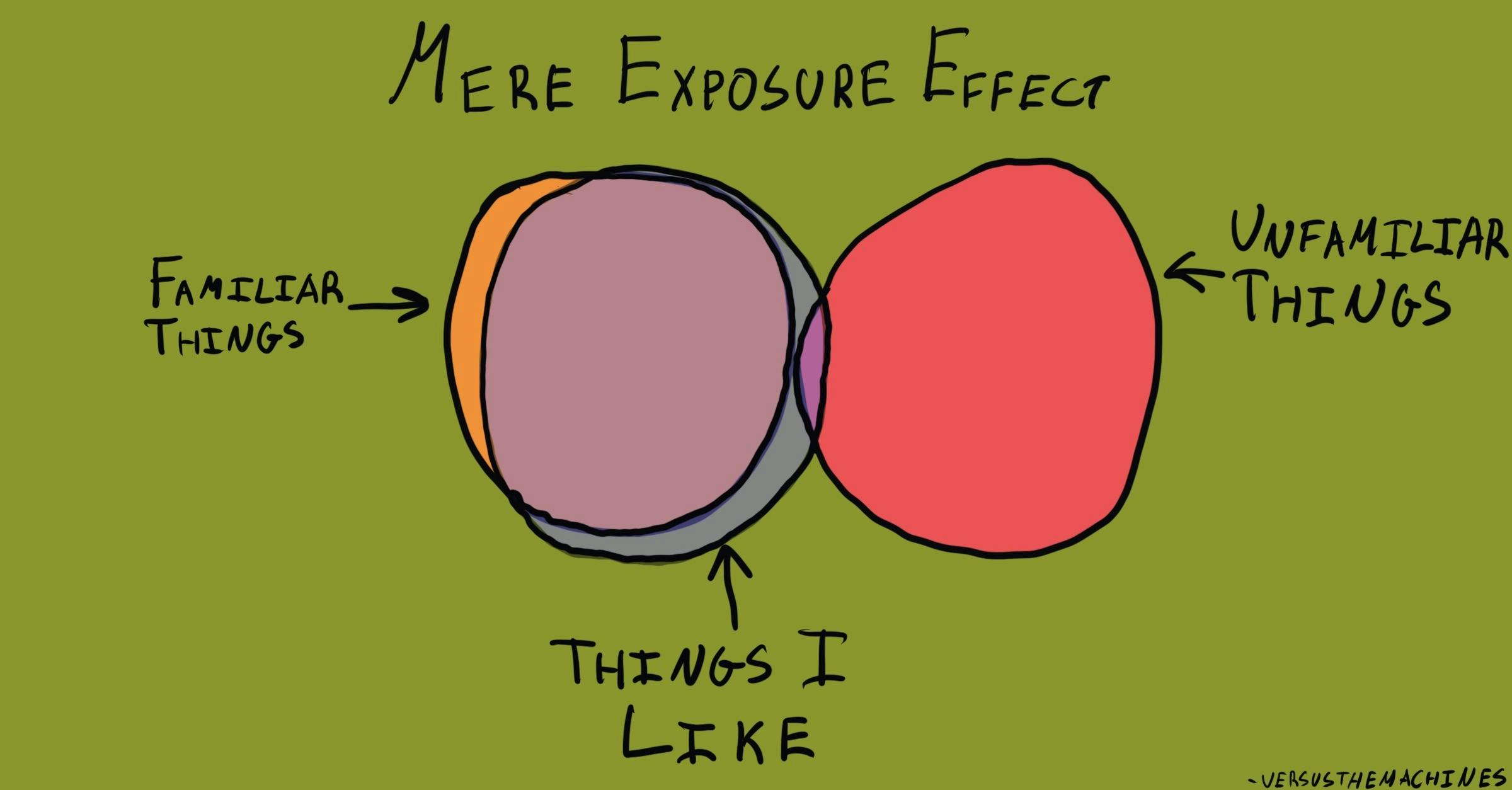

The mere exposure effect describes our tendency to develop preferences for things simply because we are familiar with them. For this reason, it is also known as the familiarity principle.

Where this bias occurs

Consider the following hypothetical situation: one day, Jane and her family decide to visit an area in town called “Little Portugal” to eat lunch at a restaurant. Jane has never eaten Portuguese food before. As a result, when Jane looks at the menu, she doesn’t recognize any of the dishes; some of the ingredients are completely foreign to her.

Jane doesn’t know what to order. Then, she notices that on the backside of the menu, there is pizza and burgers. Finally, some food she is familiar with! Jane loves pizza—she eats it all the time. So naturally, this is what Jane orders.

When the pizza arrives, Jane is reminded of her love for the dish. This affection is further reinforced after she finishes her satisfying meal.

Jane’s decision to order a dish she is familiar with, and her increased love for that meal after eating it once again, can be attributed to the mere exposure effect. We prefer things that we have been exposed to in the past, and our preference increases as our exposure does.

Debias Your Organization

Most of us work & live in environments that aren’t optimized for solid decision-making. We work with organizations of all kinds to identify sources of cognitive bias & develop tailored solutions.

Related Biases

Individual effects

The mere exposure effect can result in suboptimal decision-making. We make good choices by evaluating all possible courses of action based on their effectiveness, not their familiarity. After all, sometimes the best option is the one that is completely unfamiliar to us. Moreover, sticking with what we know limits our exposure to new things, ideas, and viewpoints. This minimizes the range of choices we are able and willing to consider when making future decisions, as well as narrows the perspective we make them from.

Take the hypothetical example above. Although Jane was satisfied with her choice to eat pizza, she could have gotten much more out of trying a new ethnic dish. She may not only have loved eating a Portuguese meal but she would have been exposed to a new cuisine—a valuable new experience that could have enriched her understanding of Portuguese culture. Maybe the next time she tried Portuguese food again she would have enjoyed it even more, thanks to the mere exposure effect.

Systemic effects

The consequences of the mere exposure effect can be much more serious when expanded to an institutional setting. A company that favors its current business model simply because management has grown familiar with it may miss out on necessary organizational and technological changes that require venturing into uncharted waters.1 In a similar vein, a government that is reluctant to deviate from “the way things have always been done” may not effectively represent the new and evolving preferences of their electorate. Finally, academic disciplines that have been strictly built around certain schools of thought may miss out on the useful conclusions that dissenting theories point to.

The mere exposure effect is also responsible for creating social norms and reinforcing harmful stereotypes. Remember: we are more likely to adopt ideas that we are repeatedly exposed to, especially by the media. A 2008 study found that exposure to faces of an Asian ethnicity led participants to develop positive attitudes towards other Asian faces shown to them.2 This indicates that the amount and nature of publicity different ethnicities receive influences their acceptance in society. Minority populations are typically represented less in Western media (and only in ways that support racial prejudices), leading the public to develop dangerous misconceptions about them.

...simple interventions, such as showing more racial minority faces on television and public billboards, could enhance White people's initial evaluative reactions toward unknown members of racial outgroups as well as positive behavioral responses toward newly encountered individuals of that race.”

– Social psychologist Leslie Zebrowitz, et al.

So, the mere exposure effect may entrench institutional and societal norms—which sometimes need to be revised or deviated from. Unfortunately, this means that those responsible for making crucial decisions within organizations come to prefer these values and ways of doing things simply because they are familiar.

How it affects product

Companies consistently take advantage of the mere exposure effect to entice customers to use their digital products. For example, when building a new app, a designer may default to a standard UI interface rather than pioneering a new design—that’s not just laziness! This way, when a new user opens up the app for the first time, they will instantly be greeted with the warm familiarity of the layout, coaxing them to continue their virtual exploration.

In a similar vein, companies may keep their logo virtually unchanged for decades, even if the font or colors feel outdated. They know this consistency will guarantee them brand recognition, and in turn, brand loyalty. After all, most customers will default to choosing the product with the logo they’ve seen a hundred times before, rather than venturing into the uncharted territory of a new one. Think of the public outrage that spewed after Twitter changed its icon from a bird to the daunting “x” symbol. It turns out that sticking to the standard is often the best decision for digital designers to guarantee customers will come back, time and time again.

The mere exposure effect and AI

Have you ever felt as though AI is really getting to know you? Maybe each time you browse movie selections on Netflix, your recommended watchlist is better tailored to your preferences (more rom-coms, less horror). Or maybe each time you banter back and forth with ChatGPT, you notice its responses are even more attuned to your questions.

Sure, this personalization is probably, in part, due to machine learning picking up on your preferences, and adjusting its algorithm to align with them. But remember, our interactions with AI are a two-way street—and we may be adjusting our preferences to align with Al. Every time we expose ourselves to a recommended watchlist or ChatGPT, we inherently become more familiar with them, and thanks to the mere exposure effect, more inclined towards them. This means that digital personalization may be more due to us getting to know AI, rather than the other way around.

Why it happens

We don’t need to be conscious of the things we are exposed to for their familiarity to have an effect on our preferences towards them. Most of the time, the mere exposure effect happens subliminally, or in other words, at a level below our awareness. In fact, researchers have found that the effect is even more powerful when we are unaware of a stimulus.3

There are two main reasons why we experience the mere exposure effect:

- It reduces uncertainty. We are less uncertain about something when we are familiar with it. We are programmed by evolution to be careful around new things because they could pose a danger to us. As we see something repeatedly without noticing bad consequences, we are led to believe it is safe. Imagine you are a caveman, and encounter two fruits: one that you’ve seen before, and one that you haven’t. Which are you more likely to eat? The cavemen who picked the bush they hadn’t seen before tended not to survive as long (for obvious reasons). We have therefore evolved to have more positive feelings about people and things we have seen before than those we haven’t seen before.

- It makes understanding and interpreting easier. In what’s known as “perceptual fluency,” we are better able to understand and interpret things we have already seen before. Consider this: for most of us, movies with complicated storylines are usually easier to understand the second time we watch them. This is because the plot and characters are familiar, which reduces the amount of new information your brain needs to process. Our mind generally looks for the path of least resistance, and so we prefer stimuli that we have already been exposed to.4

Why it is important

We should seek to avoid the mere exposure effect because it can make us miss out on valuable information and opportunities that we have never encountered before. This bias attracts us to the familiar, and as mentioned before, familiarity isn’t a good basis to evaluate things. Sometimes the new option is indeed the best option. Prioritizing what we know prevents us from venturing into these uncharted waters. This can cause us to make uninformed decisions, such as citizens who vote for politicians that they recognize from campaign ads and media coverage, rather than candidates that represent their interests. Additionally, sticking to the familiar keeps us from seizing new opportunities, like an investor who decides against supporting a new piece of cutting-edge technology because they are used to its predecessor.

In short, the mere exposure effect can make us more narrow-minded and prevent personal growth. Sticking to what we know and see on a regular basis prevents us from being open to new views and from putting ourselves in uncomfortable, unfamiliar situations that force us to become better.

How to avoid it

While it is inevitable that we develop an attachment to things we often see, the mere exposure effect may eventually counteract itself. Research has shown that too much repeated exposure eventually lessens our attraction to a stimulus as it loses novelty. We can actually start to avoid something if we are exposed too much to it. A 1990 study identifies this as “boredom” with the stimulus.5 This makes sense: you often start by liking a song and often come to love it as you become more familiar with its sound. But if you listen to the song too much, you become bored of it and don’t want to listen to it anymore.

A more proactive strategy to fight back against the mere exposure effect might be to recognize the value of diversity and new experiences. By looking for unfamiliar and different opportunities, we might limit how often we are exposed to any one stimulus.

How it all started

The earliest scientific recordings of the mere exposure effect came from the work of German psychologist Gustav Fechner and English psychologist Edward Titchener at the end of the 19th century, who wrote of a “glow of warmth” felt in the presence of something that is familiar. The effect was more thoroughly investigated by an American social psychologist called Robert Zajonc in 1968. In his experiments, Zajonc tested how subjects responded to made-up words and Chinese characters. Subjects were shown the characters a different number of times and were then tested on their attitudes towards them. Zajonc found that subjects who were shown these words the most also responded the most favorably to them.

Example 1 – Finance and domestic investment

Financial professions may be particularly impacted by the mere exposure effect. A 2015 study done by economist Gur Huberman found that financial traders were more likely to invest in domestic companies they were familiar with, even though this is not the most profitable or risk-averse strategy.

To avoid the damages of a national economic downturn, investors generally agree on the tactic of international diversification. In other words, it is wise to spread investments across companies located in different countries in case one of those countries has economic issues. There is the added benefit of many foreign stocks also being highly profitable.

Despite this, Huberman notes that “by and large, investors’ money stays in their home countries.” This is in the face of falling barriers to international investment. He argues that this “home country bias” can be attributed to “people simply prefer[ing] to invest in the familiar.” Investing in the familiar extends further: people are also more likely to invest in companies they recognize from positive media coverage or their own company’s stocks.7 The mere exposure effect may therefore cause investors to unwisely favor familiar domestic stocks over unfamiliar foreign ones.

Familiarity is associated with a general sense of comfort with the known and discomfort with—even distaste for and fear of—the alien and distant.”

– Economist Gur Huberman

Example 2 – Journal ranking in academia

The mere exposure effect is also present in academia. A study done in 2010 by Alexander Serenko and Nick Bontis used data given by 233 active researchers to determine how they ranked academic journals. They hypothesized that the exposure would be at play if these participants assigned greater ranking to journals simply because they are more familiar with them rather than basing their ranking on an objective assessment of the journal’s contribution to the field.

Their analysis confirmed the role of the mere exposure effect. More specifically, they found that researchers who had previously published or worked for a particular journal rated it higher than those who had not and that perceptions of a journal were strongly correlated with researchers’ degree of familiarity with it.8

Summary

What it is

The mere exposure effect is our tendency to develop preferences for things simply because we are familiar with them.

Why it happens

There are two main reasons why we experience the mere exposure effect. First, we are less uncertain about something when we are familiar with it. We have evolved to be careful around new things because they could pose a danger to us. This uncertainty is reduced as we see something repeatedly without noticing bad consequences.

Second, in what’s known as “perceptual fluency,” we are better able to understand and interpret things we have already seen before. Our mind generally looks for the path of least resistance, and so we prefer stimuli that we have already been exposed to.

Example #1 - Finance and domestic investment

Professions in finance may be particularly impacted by the mere exposure effect. A 2015 study found that financial traders were more likely to invest in domestic companies they were familiar with, even though this is not the most profitable or risk-averse strategy. This “home country bias” was attributed to investors’ familiarity with the firms.

Example #2 - Journal ranking in academia

The mere exposure effect is present in academia. A study done in 2010 used data given by 233 active researchers to determine how they ranked academic journals. It concluded that researchers assigned journals higher ranking on the basis of their familiarity with them rather than an objective assessment of the journal’s contribution to the field.

How to avoid it

The mere exposure effect may eventually counteract itself. Research has shown that too much exposure may limit and then detract from our attraction to a stimulus. A more proactive strategy might be to recognize the value of diversity and new experiences. By looking for unfamiliar and different experiences, we might limit how often we are exposed to any one stimulus.

Related TDL article

The Devil You (Expect to) Know: Political Reconciliation

This article argues that more empathy and understanding between citizens is needed in a divided political environment. The mere exposure effect and imagined contact hypothesis are relevant in achieving this objective, pointing to the need for more interaction (both real and imagined) between people of different backgrounds and political affiliations.