The Whorf Hypothesis

The Basic Idea

If you’ve spent any amount of time online, you might have seen an article titled along the lines of “10 words we wish we had in English” – even major outlets like the BBC1 and The Guardian2 have indulged! The format is simple. The article lists 10 words, like sobremesa (Spanish for when you stay chatting in a restaurant for too long) or kummerspeck (German for the weight gain from emotional eating), and probably a few relatable, witty remarks. The article usually ends by mourning the lack of English translation.

As behavioral scientists, we might think to ask: Are there really untranslatable words? Are there certain thoughts you can only have in certain languages?

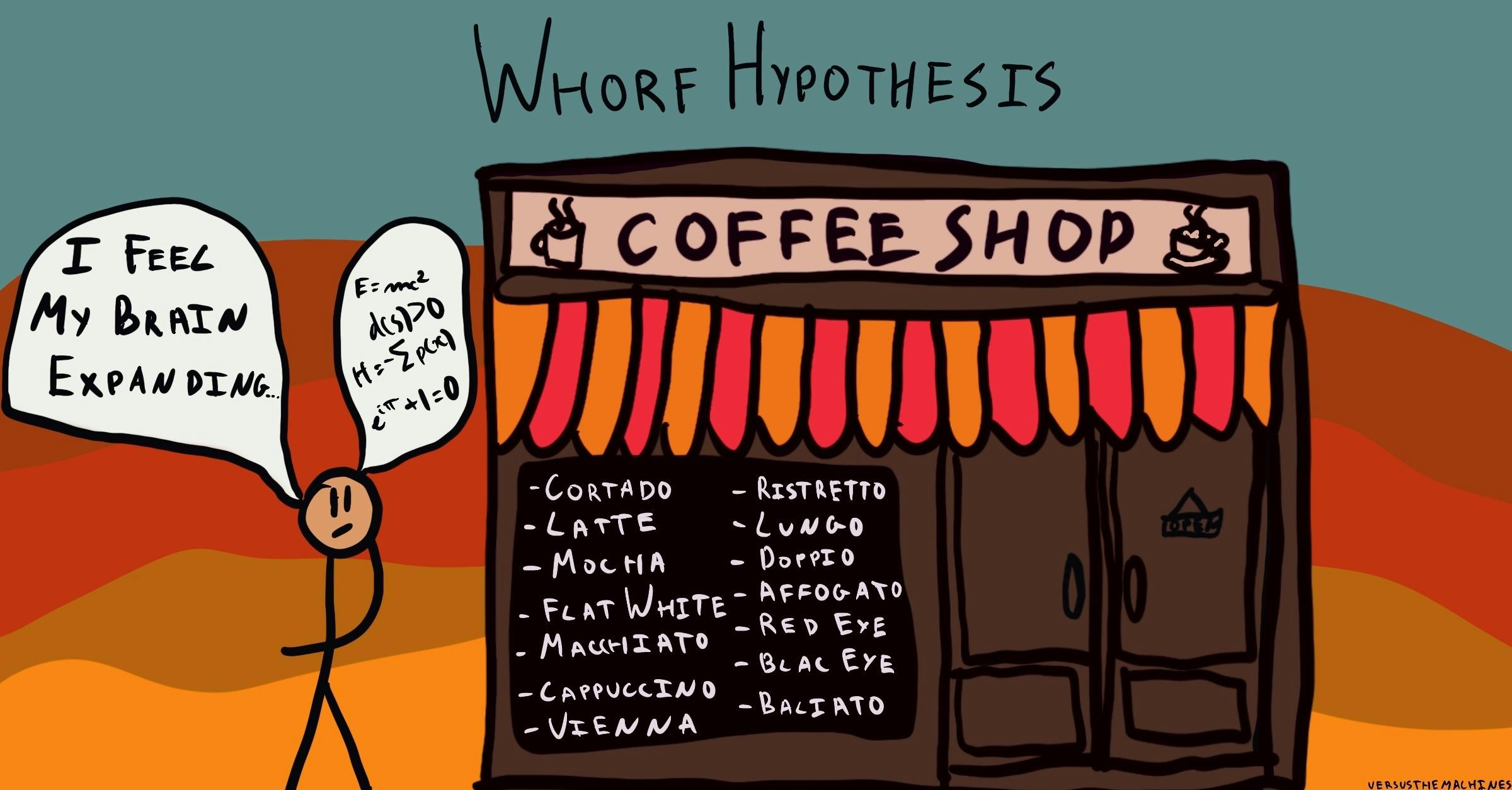

The “Whorf Hypothesis” (also known as the “Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis” or “Linguistic Relativism”) is an umbrella term for the claim that the language you speak determines or influences what you can think. If you speak English, there are certain thoughts you can have; if you speak Spanish or German, there are different thoughts you can have. Certain words are untranslatable because only certain languages can convey those thoughts.

Does the language we speak shape or determine what we can think? What is the relationship between language and thought?