Why do we tend to think that things that happened recently are more likely to happen again?

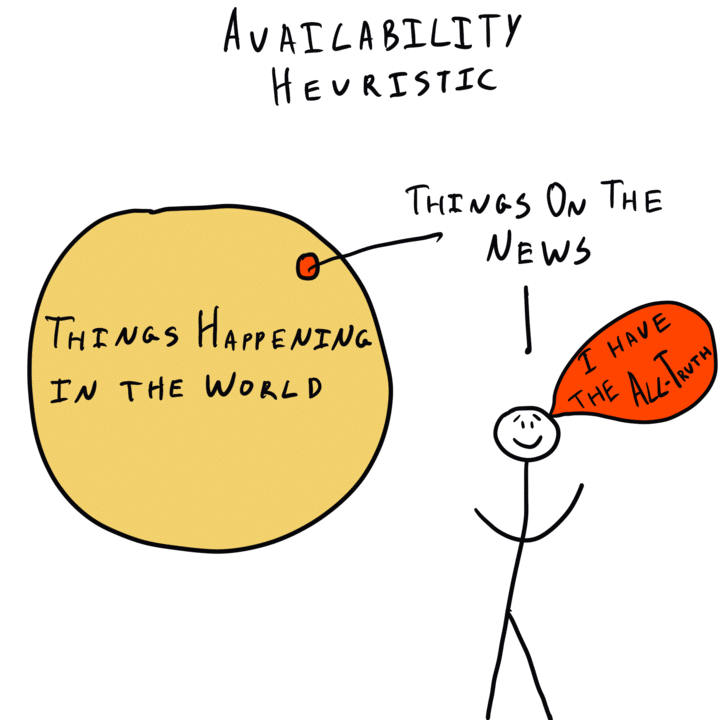

Availability Heuristic

, explained.What is the availability heuristic?

The availability heuristic describes our tendency to use information that comes to mind quickly and easily when making decisions about the future.

Where this bias occurs

Imagine you are a manager considering either John or Jane, two employees at your company, for a promotion. Both have a steady employment record, though Jane has been the highest performer in her department during her tenure. However, in Jane’s first year, she accidentally deleted a company project when her computer crashed. With this incident in mind, you decide to promote John instead.

In this hypothetical scenario, the vivid memory of Jane losing that file likely weighed more heavily on your decision than it should have. This unequal evaluation is due to the availability heuristic, which suggests that singular memorable moments have an outsized influence on decisions when compared to less memorable ones.