Why are we swayed by those around us?

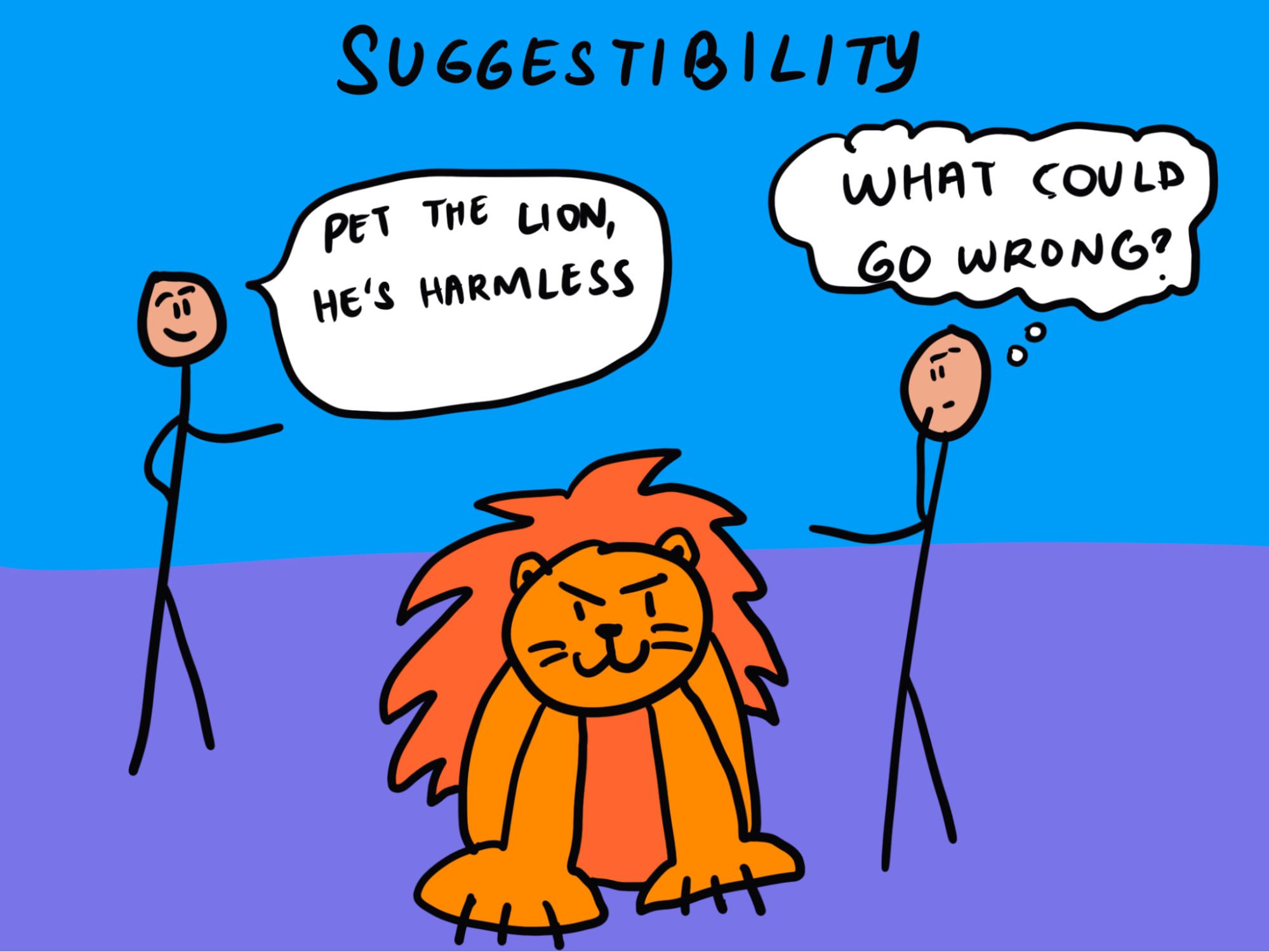

Suggestibility

, explained.What is Suggestibility?

Suggestibility is the tendency to accept and act on ideas or information suggested by others, often without critical analysis or independent judgment. In some cases, it involves the capacity for physical and verbal suggestions to elicit responses to actions outside of an individual’s conscious awareness.12

Where this bias occurs

People are considered suggestible if they act or accept suggestions based on the input of others. It is a trait that individuals have to varying degrees and the factors influencing how suggestible we are include our self-esteem, age, upbringing, assertiveness, and situational factors.1 Researchers also believe that lack of knowledge or flawed organization surrounding the subject matter being conveyed can also impact a person’s level of suggestibility.15

Imagine the following scenario. During a team meeting, the senior project manager casually mentions that one specific brand of software is "probably the best option" for an upcoming project. Even though the team hasn’t reviewed other options yet and has no prior experience with this particular software, several members immediately agree and support the suggestion, assuming the manager must have reliable insight. As a result, they skip a thorough evaluation of alternatives and proceed with the recommended software.

This example demonstrates how suggestibility can lead individuals or groups to hastily adopt an idea without fully questioning or analyzing it, potentially resulting in suboptimal decisions or missed opportunities to explore better alternatives that could have been uncovered through a little bit of thought or reflection.

Another example of suggestible behavior in our everyday life is contagious yawning.2 Contagious yawning happens when a person starts yawning after seeing another person yawn, even if the first person is not tired. Yawning is an example of suggestibility because we are influenced by the behavior of others without being consciously aware of it.2

Suggestibility is perhaps one of the most important concepts in the history of modern psychology and psychiatry. Over the years, it has been equated to a range of other cognitive phenomena and human traits, including gullibility and persuasibility, hypnosis, the placebo effect, and neuroticism.19 There is no single trait of suggestibility and can take a number of different forms that do not necessarily intersect.

Researchers looking at suggestibility have proposed two different kinds of suggestible influence and two kinds of suggestibility corresponding to them: direct and indirect.13 Direct suggestion involves overt, unhidden influence, such as someone directly telling you that ‘you shouldn’t smoke near children because it’s bad for their health.’ Indirect suggestion, on the other hand, concerns influence that is hidden, which subtly shapes perceptions by encouraging individuals to interpret or align with the suggested choice themselves. Subliminal messages, or hidden words or images that are not consciously perceived but that can influence a person’s attitudes or behaviors, constitute a type of indirect suggestion and can often be found in advertisements.

Within these two distinct types of suggestibility, there are three primary areas effects which depend on the context and type of influence:14

- The placebo effect: When an individual responds positively to a medical treatment or intervention because they believe it will work, even if the medication has no active ingredients. This effect underscores the powerful connection between the mind and the body and how our mindset plays a role in the way we feel.

- Hypnotic suggestibility: The degree to which an individual responds to suggestions from another person while under the influence of hypnosis. In this state, a person’s critical thinking and conscious control are reduced. Hypnotic suggestibility is part of the broader psychological trait of direct verbal suggestibility, which refers to the tendency of an individual to accept and act on hypnotic suggestions that are communicated explicitly through verbal instructions.

- Interrogative suggestibility: The extent to which an individual is influenced by leading questions, pressure, or suggestions during questioning, such as during police interviews or psychological evaluations. Highly suggestible individuals may alter their answers in response to the authority they are confronted with, even if it isn’t directly hostile

Both the placebo effect and interrogative suggestibility are considered indirect suggestion, while hypnotic suggestibility is categorized as direct suggestion.