Why do our decisions depend on how options are presented to us?

Framing Effect

, explained.What is the Framing Effect?

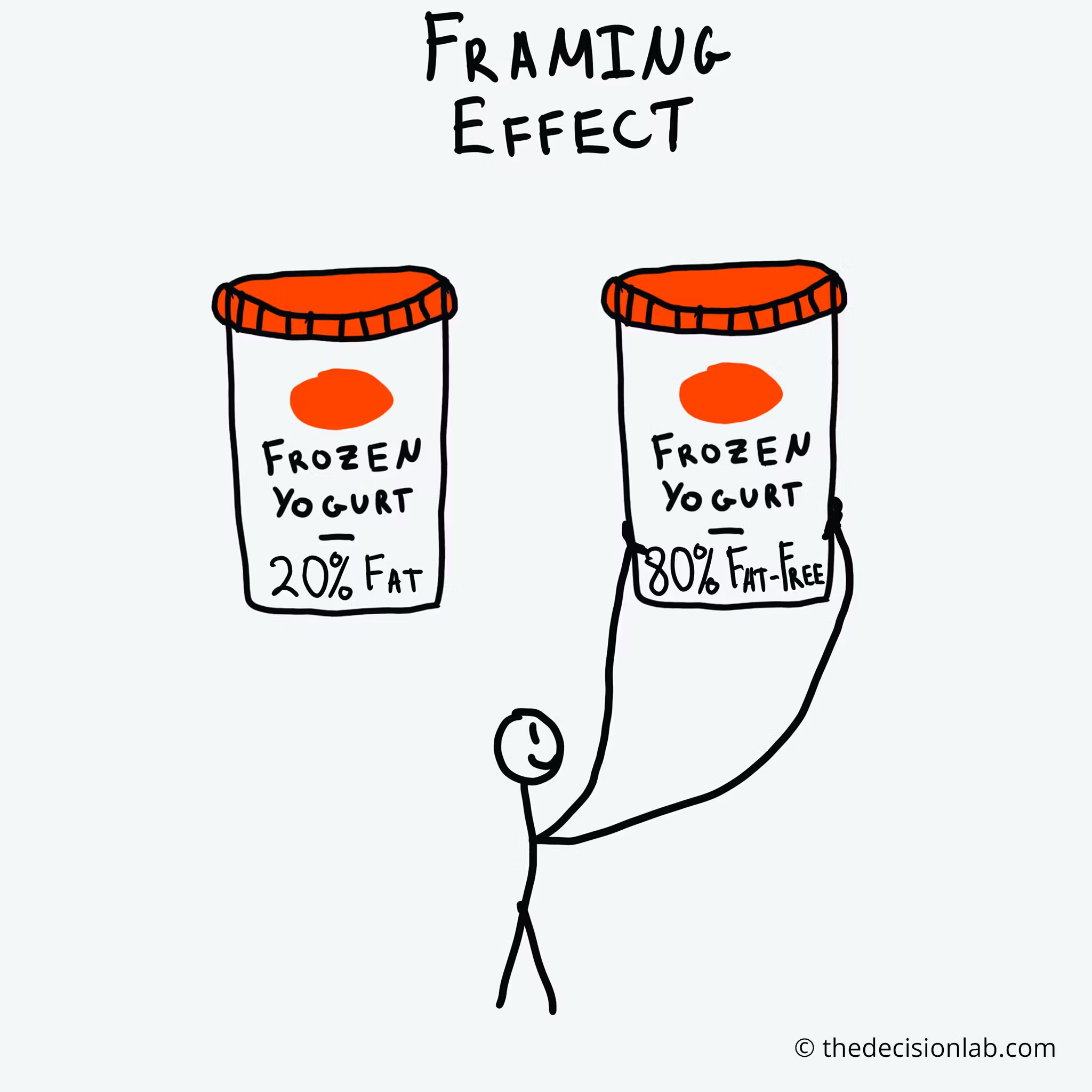

The framing effect is when our decisions are influenced by the way information is presented. Equivalent information can be more or less attractive depending on what features are highlighted.

Where this bias occurs

Consider the following hypothetical: John is shopping for disinfectant wipes at his local pharmacy. He sees several options, but two containers of wipes are on sale. One is called “Bleachox” and the other is called “Bleach-it.”

Both of the disinfectant wipes Jon is considering are the same price and contain the same number of wipes. The only difference Jon notices is that the Bleachox wipes claim to “kill 95% of all germs,” whereas the Bleach-it wipes say: “only 5% of germs survive.” After comparing the two, John chooses the Bleachox wipes. He doesn’t like the sound of germs ‘surviving’ on his kitchen counter.

John’s decision to buy the Bleachox over Bleach-it wipes was informed by the framing effect. Although both products were equally effective at fighting germs, and essentially claimed the same thing, their claims were framed differently. Bleachox highlighted the percentage of germs it did kill (a positive attribute), whereas Bleach-it highlighted how many germs it did not kill (a negative attribute).