Why do some ideas prompt other ideas later on without our conscious awareness?

Priming

, explained.What is priming?

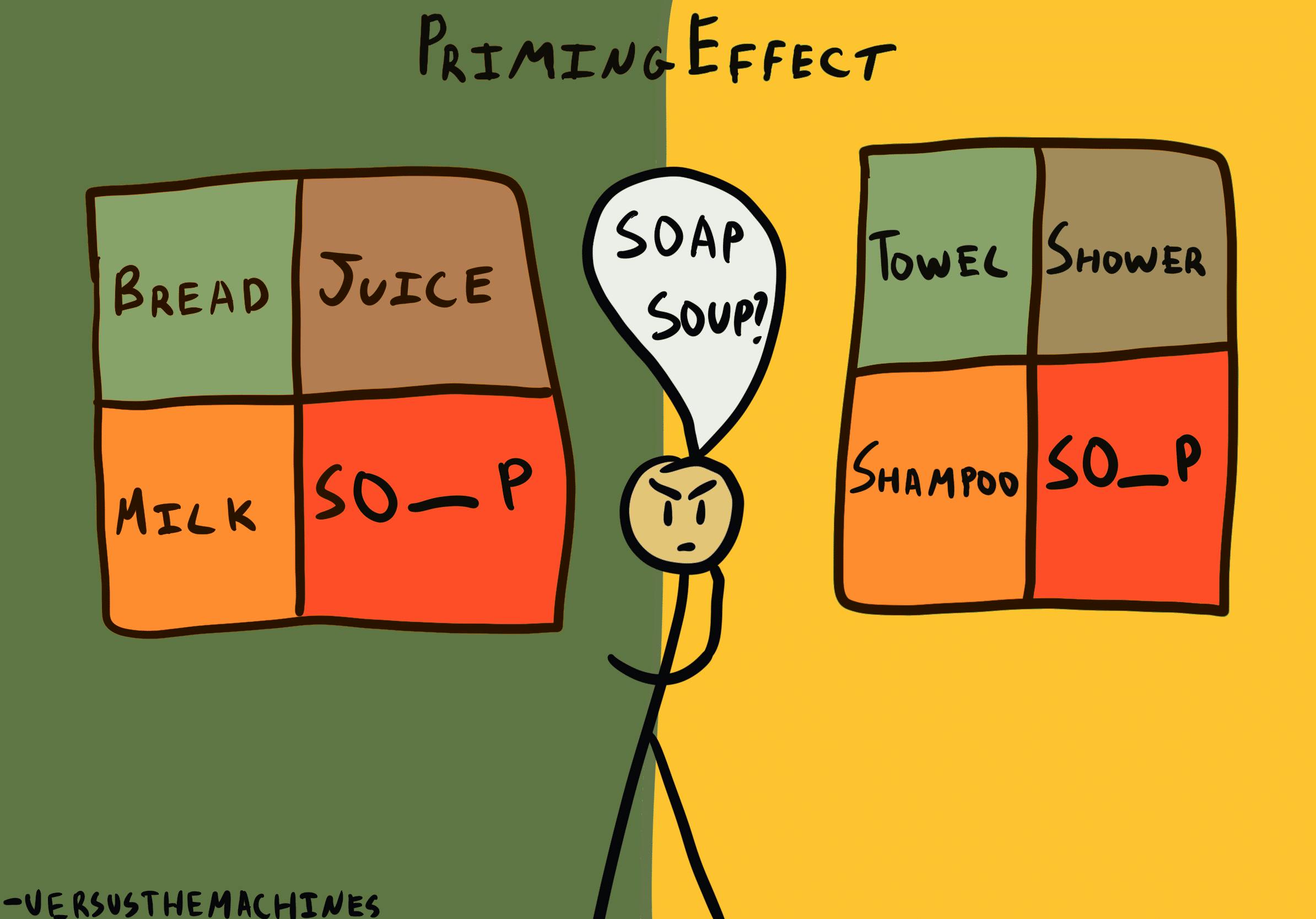

Priming, or, the priming effect, occurs when an individual’s exposure to a certain stimulus influences their response to a subsequent prompt, without any awareness of the connection. These stimuli are often related to words or images that people see during their day-to-day lives.

Where this bias occurs

To illustrate priming in its simplest form, we can look at word association tasks. If you are first presented with the word “doctor” a moment later, when presented with a list of unrelated words, you will recognize “nurse” much faster than “cat.” Unconsciously, your brain makes the link between the two medical workers, as the two semantically related words are closely connected in your memory.

The priming effect is also commonly found when you try to remember a song’s lyrics. If the lyrics are ambiguous and you struggle to make them out, your brain will fill in the missing information as best as it can—usually by making use of information that you have been primed to remember. Thus, you may hear different lyrics than what is being sung because of the priming effect.