Why do we value immediate rewards more than long-term rewards?

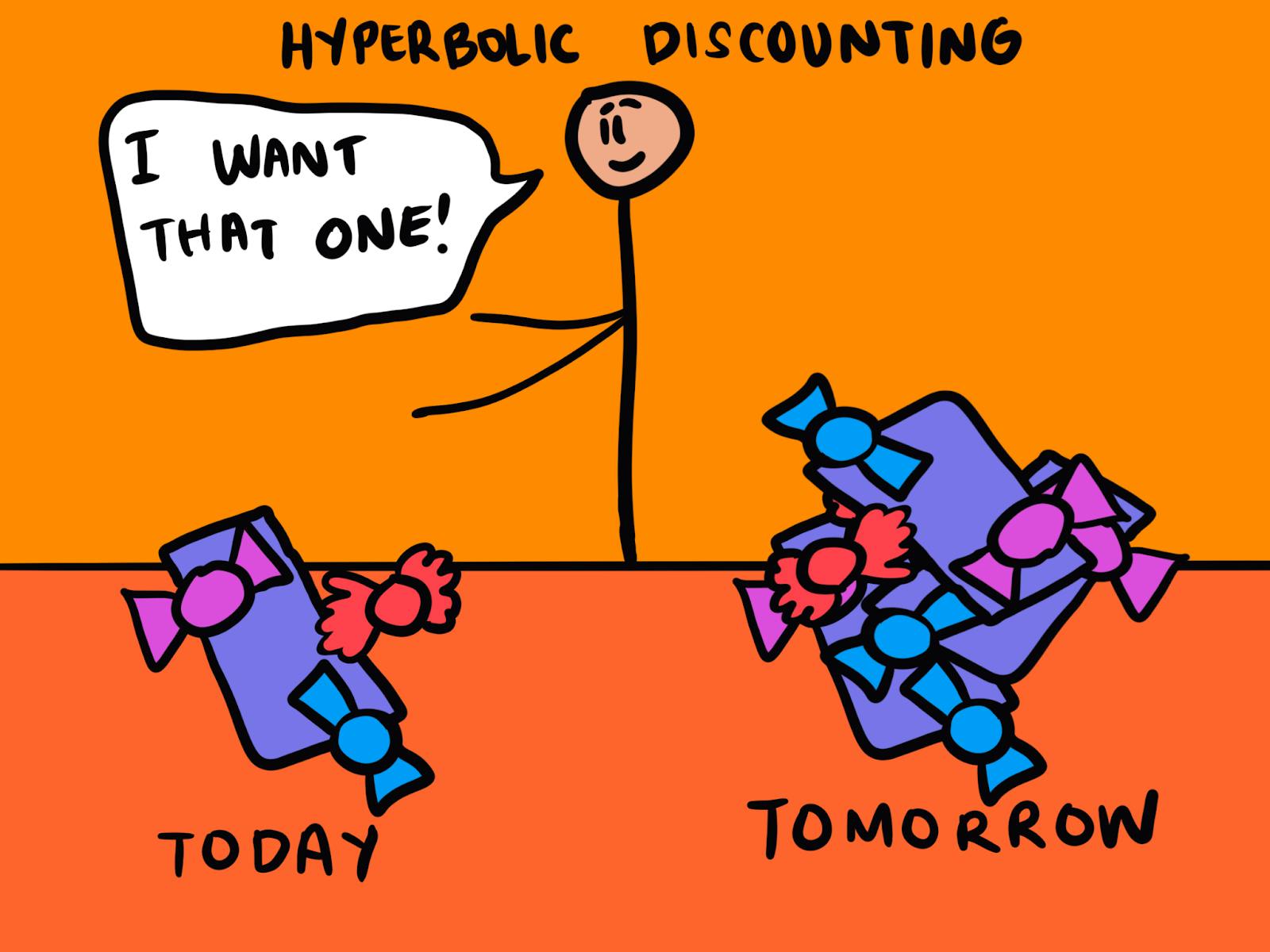

Hyperbolic Discounting

, explained.What is Hyperbolic Discounting?

Hyperbolic discounting is our inclination to choose immediate rewards over rewards that come later in the future, even when these immediate rewards are smaller.

Where this bias occurs

Consider the following hypothetical: John buys a lottery ticket every week. He hopes to someday win big. One fortunate day, against all odds, he does. John is now worth just over $5 million.

After a frenzy of celebrations and hugs, John drives to the lottery offices to claim his prize. When he arrives, the lottery director gives him a choice: he could either claim the $5 million now, or he could choose to receive $250,000 every year for the rest of his life instead. John is only 35. Quick mental math points to the second option generating more revenue for John if he lives past the age of 55—which he plans on doing. But, John imagines having a seven figure total in his bank account and relishes the idea of all the things he could buy today.

John decides to take the first option, even though he will likely receive less money from it in the long-run. His preference towards immediate benefits over future gain can be attributed to hyperbolic discounting.