Why is the news always so depressing?

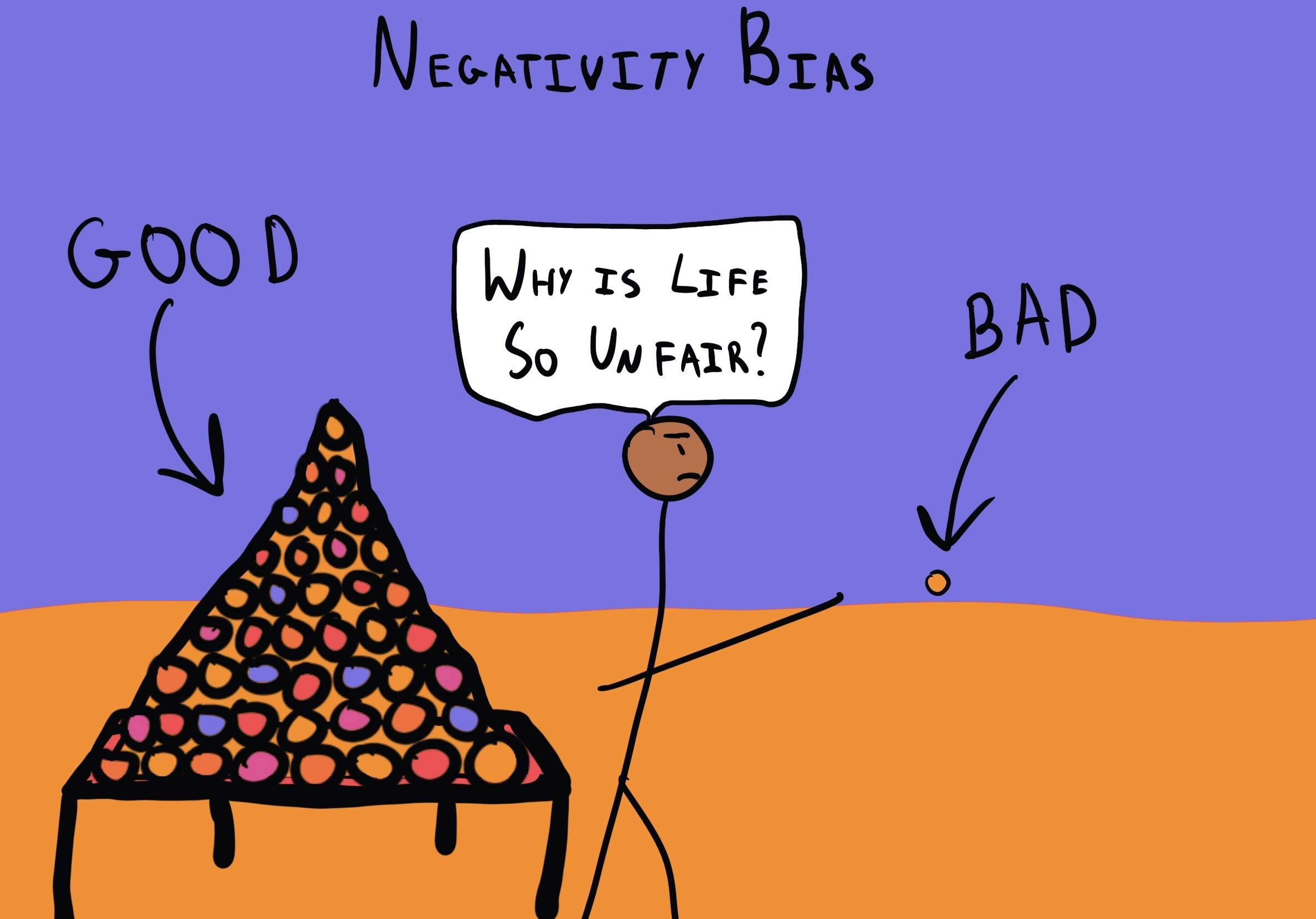

Negativity Bias

, explained.What is the Negativity Bias?

The negativity bias is a cognitive bias that results in adverse events having a more significant impact on our psychological state than positive events. Negativity bias occurs even when adverse events and positive events are of the same magnitude, meaning we feel negative events more intensely.1

Where this bias occurs

Negativity bias is a well-studied and long-understood concept. Negativity bias causes amplified emotional responses to negative events compared to positive events of equal magnitude. Negativity bias is linked to loss aversion, a cognitive bias that describes why the pain of losing is psychologically twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining.2

Much of today’s political discourse occurs online and while this may expose us to greater perspectives, it also leaves the door open for misunderstanding. We often criticize “the other side” and assume ill-intent when we read political posts that don’t align with our values. And while sometimes there is hostility imbedded certain content, it isn’t always the case. Because of our predisposition to focus on and scrutinize the negative, posts that express anger or hostility grab our attention and inform our perceptions. By nature, we extrapolate and then use these negative impressions to cast future judgment.