Why do we misjudge groups by only looking at specific group members?

Survivorship Bias

, explained.What is the Survivorship Bias?

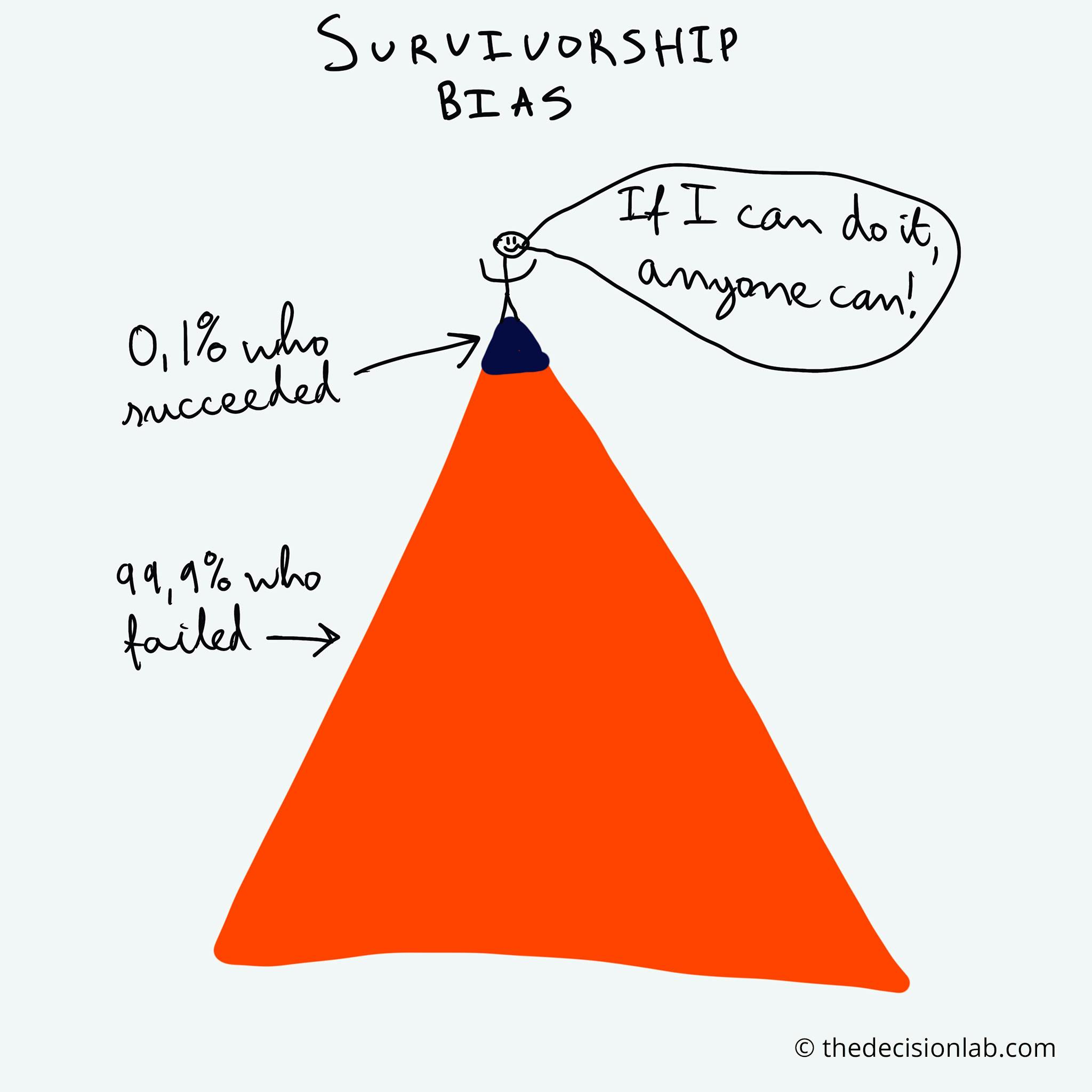

Survivorship bias is a cognitive shortcut that occurs when a successful subgroup is mistaken as the entire group, due to the invisibility of the failure subgroup. The bias’ name comes from the error an individual makes when a data set only considers the “surviving” observations, excluding points that didn’t survive.1

Where this bias occurs

Examples of survivorship bias are noticeable in a wide range of fields, particularly in the corporate world. Students in business school can recall how “unicorn start-ups” are commonly applauded within the classroom, serving as an example of what students should strive for — an archetypal symbol of success. Even though Forbes reported that 90% of start-ups fail, entire degrees are dedicated to entrepreneurship, with dozens of students claiming that they will one day find a start-up and become successful.2

By looking at successful start-up founders like Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, and Mark Zuckerberg, an individual could conclude that to reach their level of success, they have to follow some magic formula. They must simply have an idea, drop out of school, and dedicate time to their big idea.

In Scientific American, Professor Michael Shermer and Larry Smith from the University of Waterloo describe how advice about commercial successes distorts individual perceptions, as we tend to ignore college dropouts who don’t become successful entrepreneurs or businesses that have failed.3

Simply put, many forget that these unicorn start-ups are just that: unicorns. Of the thousands of people who attempt to follow the same paths as these business tycoons, most fail. Still, their stories of failure aren’t shared as widely as success stories, giving others an inflated idea of our capabilities and potential achievements. That is not to say that hard work and talent will not lead to success, but rather that, as a society, we tend to ignore common failures and hold onto success stories as proof of what is possible. Instead, in this hypothetical, we must also consider that things like luck, timing, connections, and socioeconomic background have played a part in well-known founders’ achievements.