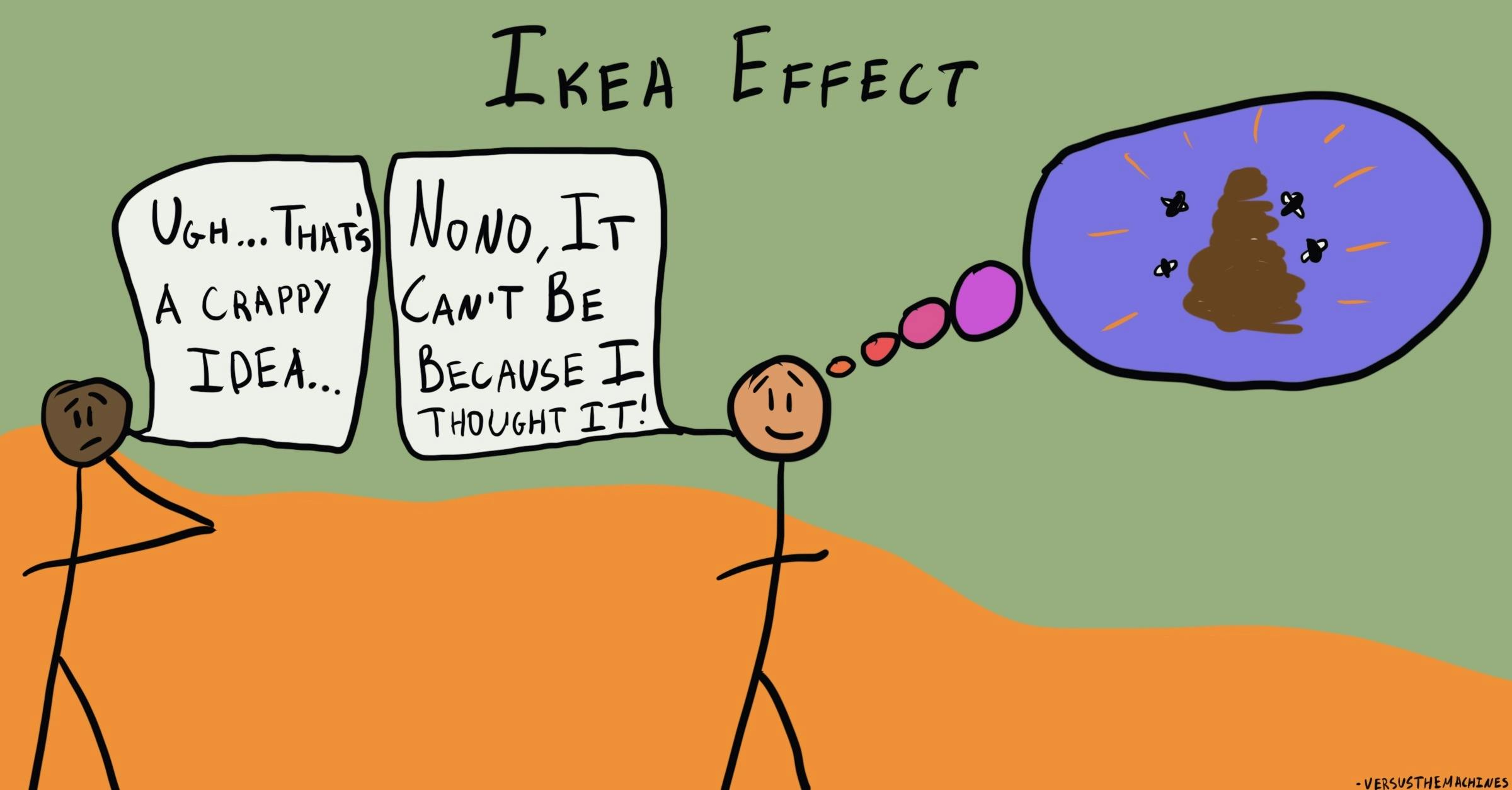

Why do we place disproportionately high value on things we helped to create?

IKEA Effect

, explained.What is the IKEA effect?

The IKEA effect, named after everyone’s favorite Swedish furniture giant, describes how people tend to value an object more if they make (or assemble) it themselves. More broadly, the IKEA effect speaks to how we tend to like things more if we’ve expended effort to create them.

Where this bias occurs

Alex decided he needed some new furniture to spruce up his apartment, so he made a trip to IKEA and picked out a nice coffee table with lots of umlauts. As with all IKEA furniture, he takes it home in a box and puts it together himself. Standing back and admiring his handiwork, he’s rewarded with a sense of accomplishment that makes all that frustrating labor worthwhile.

Sometime later, Alex is moving and decides to sell his furniture. After doing some Googling, he sees that very similar tables are being sold online for $100, but he decides to list his for $125. His subjective valuation of the coffee table is higher than its actual market value simply because he built it himself. Unfortunately, the effort Alex put into assembling the table won’t matter to buyers, and he’ll have difficulty selling it without reducing his asking price. This is a classic example of the IKEA effect, where our involvement in creating an item makes us feel as if it's worth more than it really is.