Why do we value items more if they belong to us?

Endowment Effect

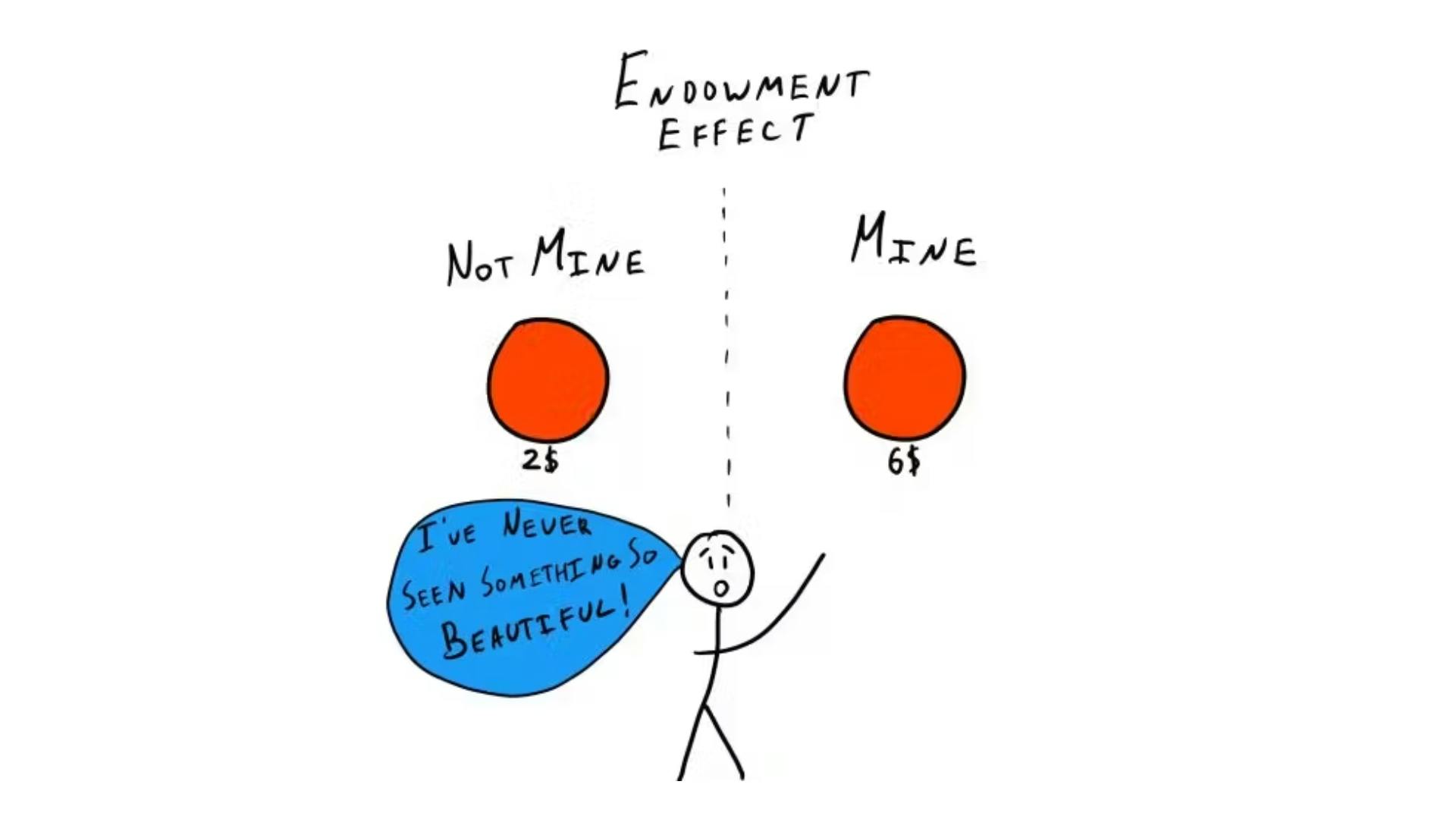

, explained.What is the Endowment Effect?

The endowment effect describes how people tend to value items that they own more highly than they would if they did not belong to them. This means that sellers often try to charge more for an item than it would cost elsewhere.

Where this bias occurs

Imagine you just upgraded your laptop and you want to sell your old one. Let’s say you bought it several years ago, brand new, for $1,000. It’s still in great condition and runs well, so you list it online for $900, thinking you’re giving people a great deal—after all, it would set someone back at least $1,000 to buy the newest model of the laptop today. Feeling confident, you sit back and wait for the responses to roll in.

To your dismay, you only receive a few messages, and everyone is lowballing you! One person offers $600 and another $400. The feedback is clear: everyone says that your laptop is too expensive. Someone even boasts that they can get it for less elsewhere. Your laptop has depreciated much more than you thought, and thanks to the endowment effect, you set the price higher than the market is willing to pay. Simply because the laptop is yours, you value it more than all those potential buyers who only see it as another used electronic device.