Deductive Research

What is Deductive Research?

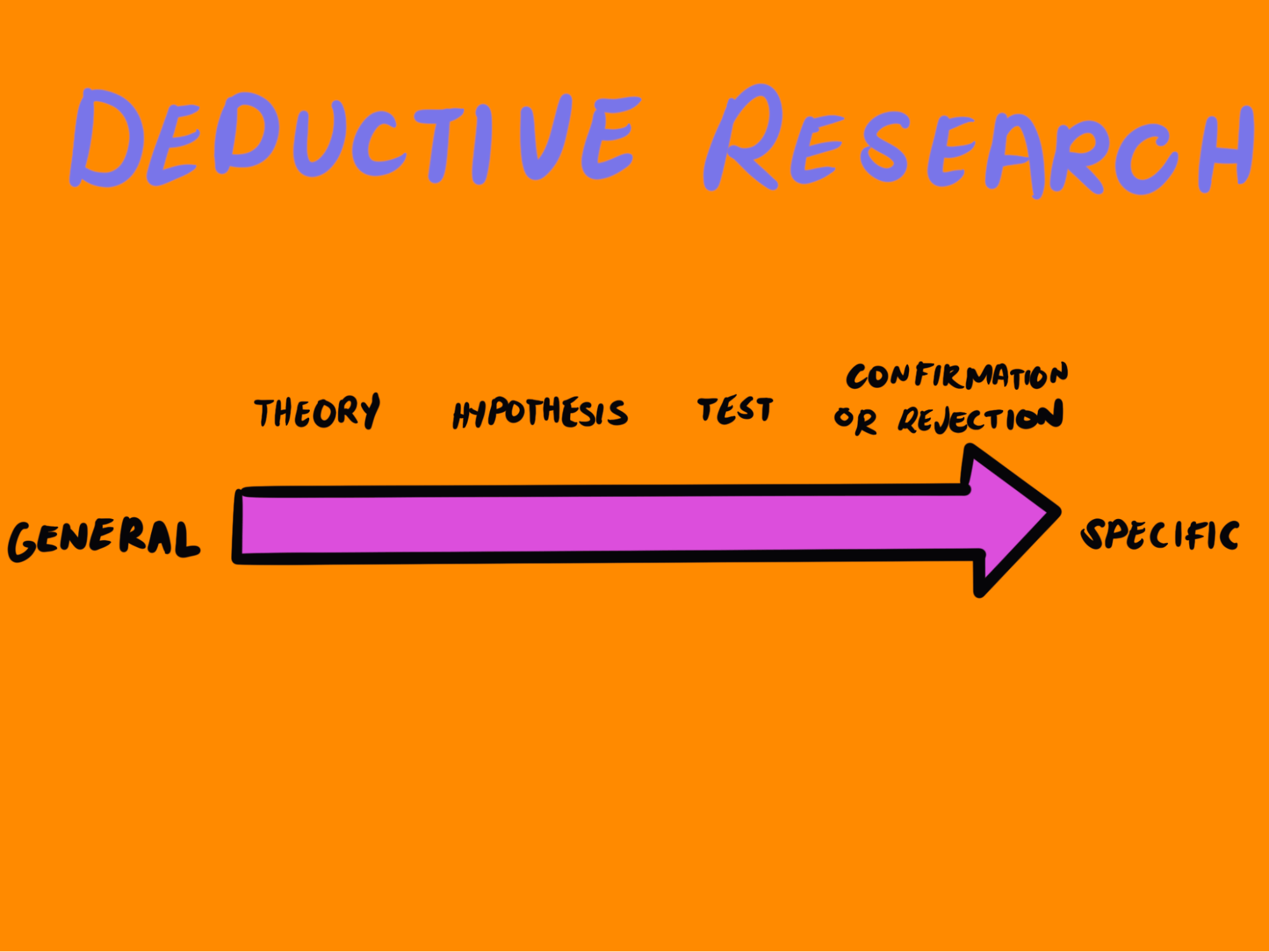

Deductive research is a systematic approach in which researchers begin with a theory or hypothesis and design a structured study to test it. This ‘top-down’ method moves from the general to the specific: researchers begin with a broad theoretical framework, then derive specific hypotheses, and finally collect and analyze data to determine whether the hypothesis is supported or not.

The Basic Idea

Imagine a detective working on a criminal case. She receives an anonymous tip that a specific person, let's call him Alex, was involved in a recent crime. The detective develops a hypothesis based on this tip that Alex is the one who committed the crime. The detective then sets out to test this hypothesis by gathering evidence, interviewing witnesses, and cross-checking alibis.

As the detective proceeds with the investigation, each piece of evidence is carefully examined to determine whether it supports or contradicts the hypothesis. For example, if Alex's fingerprints are found at the scene, that supports the hypothesis. If Alex has an airtight alibi, however, that challenges it.

The detective’s approach mirrors deductive research. She starts with a theoretical framework and a solid hypothesis, then looks for evidence to support or disprove it, eventually reaching a conclusion based on the findings. If the evidence she finds supports the hypothesis, the detective can more confidently assert Alex's involvement. If not, she might have to reject the initial assumption and search for a new lead.

Deductive research is the antithesis of inductive research, a ‘bottom-up’ approach that begins with data collection and analysis to generate broader theories and hypotheses based on the patterns observed in the data. In simple terms, deductive research is ‘theory to data’ while inductive research is ‘data to theory.’ While both methods can be applied across different types of data, deductive research is commonly associated with scientific quantitative data (e.g., numerical data collected through surveys or experiments), while inductive research lends itself to qualitative data (e.g., verbal or contextual data collected through interviews, ethnographies, or social listening).1

To no surprise, deductive research is based on the cognitive function of deductive reasoning, a process we use every day to make decisions and solve problems.2 Consider the following example: you have the premise that if it is raining, you will need an umbrella. You look outside before leaving the house and realize that it’s raining. You therefore conclude that you will need an umbrella. In this case, the reasoning starts with a general rule (when it rains, an umbrella is needed), which is then applied to a specific situation (a rainy day), leading to the logical conclusion that you should bring an umbrella. We use our ideas and premises like building blocks to develop conclusions for specific situations in our everyday lives. Likewise, researchers use this type of thinking to draw conclusions from the evidence they generate through their inquiries.

Deductive research is widely used across various fields where there’s a need to test theories or hypotheses in a structured way, particularly when the goal is to establish causal relationships or validate established theories. In market research, deductive research is used to test hypotheses about consumer behavior or product performance, while in education, it can be applied to the evaluation of teaching methods or policy interventions.

There are, of course, two methods of dealing philosophically with every subject—deductively and inductively. The deductive method is the mode of using knowledge, and the inductive method is the mode of acquiring it.

— Henry Mayhew, English journalist and playwright

About the Author

Laurel C Newman, Ph.D.

Laurel Newman is a social psychologist and an applied behavioral scientist. She began her career as a psychology professor and department chair at Fontbonne University, leaving academia in 2018 to help create a behavioral science function at Maritz. Laurel consults, conducts research, and delivers corporate behavioral science curricula. She writes articles and books on topics such as employee engagement and how to build a behavioral science function within an organization. Laurel has a Ph.D. in Social and Personality Psychology from Washington University in St. Louis. She works in the Experience Center of Expertise at Edward Jones and is co-founder and advisor to the employee loyalty startup Whistle Systems.