Why do we think our current preferences will remain the same in the future?

Projection Bias

, explained.What is Projection Bias?

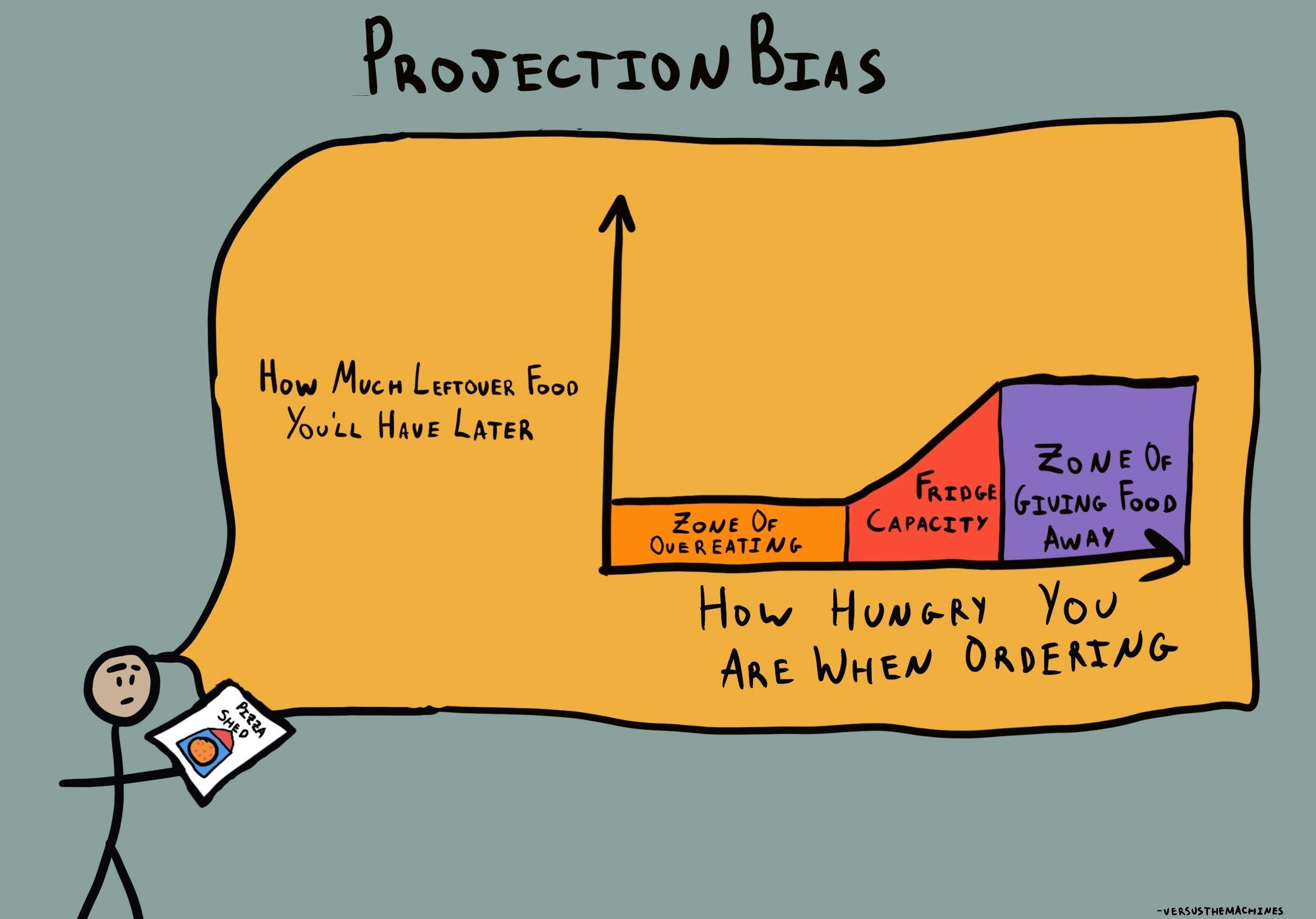

The projection bias is a self-forecasting error where we overestimate how much our future selves will share the same beliefs, values and behaviors as our current selves, causing us to make short-sighted decisions.

Where this bias occurs

Imagine that you are starving and go to the grocery store to get some food. You might load up your cart with heaps of snacks: chips, chocolate, pizza, crackers. You get home, pop the pizza in the oven and start eating some other things you bought while it cooks. When the pizza is done, you realize you’re not hungry anymore. How can that be — you were starving! Now you have all this junk food that you don’t even want anymore.

That’s the projection bias at play. In this classic scenario, we predict how hungry we were going to be while we are in a hungry state, causing us to make decisions that do not consider that our future selves, once no longer hungry, would not feel the same. We project our current state of hunger into our predictions of how much we could eat later and as a result waste money and food. The popular phrase, “having eyes bigger than your stomach”, is really about our current vision for our future self being inaccurate.