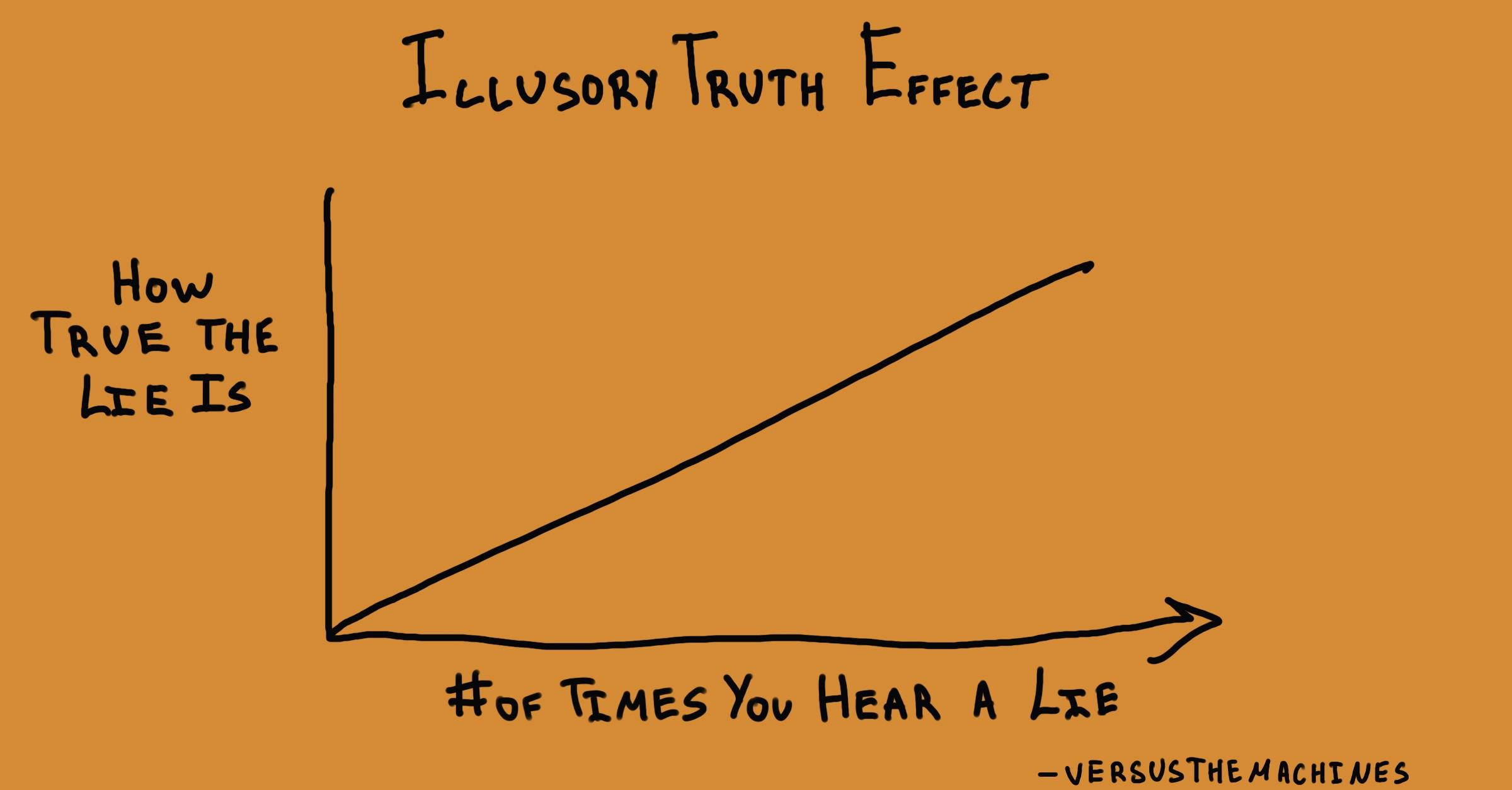

Why do we believe misinformation more easily when it’s repeated many times?

Illusory Truth Effect

, explained.What is the Illusory Truth Effect?

The illusory truth effect, also known as the illusion of truth, describes how when we hear the same false information repeated again and again, we often come to believe it is true. Troublingly, this even happens when people should know better—that is, when people initially know that the misinformation is false.

Where this bias occurs

Imagine there’s been a cold going around your office lately and you really want to avoid getting sick. Over the years, you’ve heard a lot of people say that taking vitamin C can help prevent sickness, so you stock up on some tasty orange-flavored vitamin C gummies.

You later find out that there’s no evidence vitamin C prevents colds (though it might make your colds go away sooner!).18 However, you decide to keep taking the gummies anyways, feeling like they still might have some preventative ability. This is an example of the illusory truth effect, since your repeated exposure to the myth created the gut instinct that it was true.

Encountering repeated instances of false information like this can affect our judgments of truth, causing us to believe statements that we might have initially evaluated more skeptically. How often have you heard that goldfish have a three-second memory, that coffee is dehydrating, or that gum takes seven years to digest? Even if we originally receive these myths with a critical mind, we eventually begin to believe there is some truth to them—simply because of repetition.