Why do we prefer doing something to doing nothing?

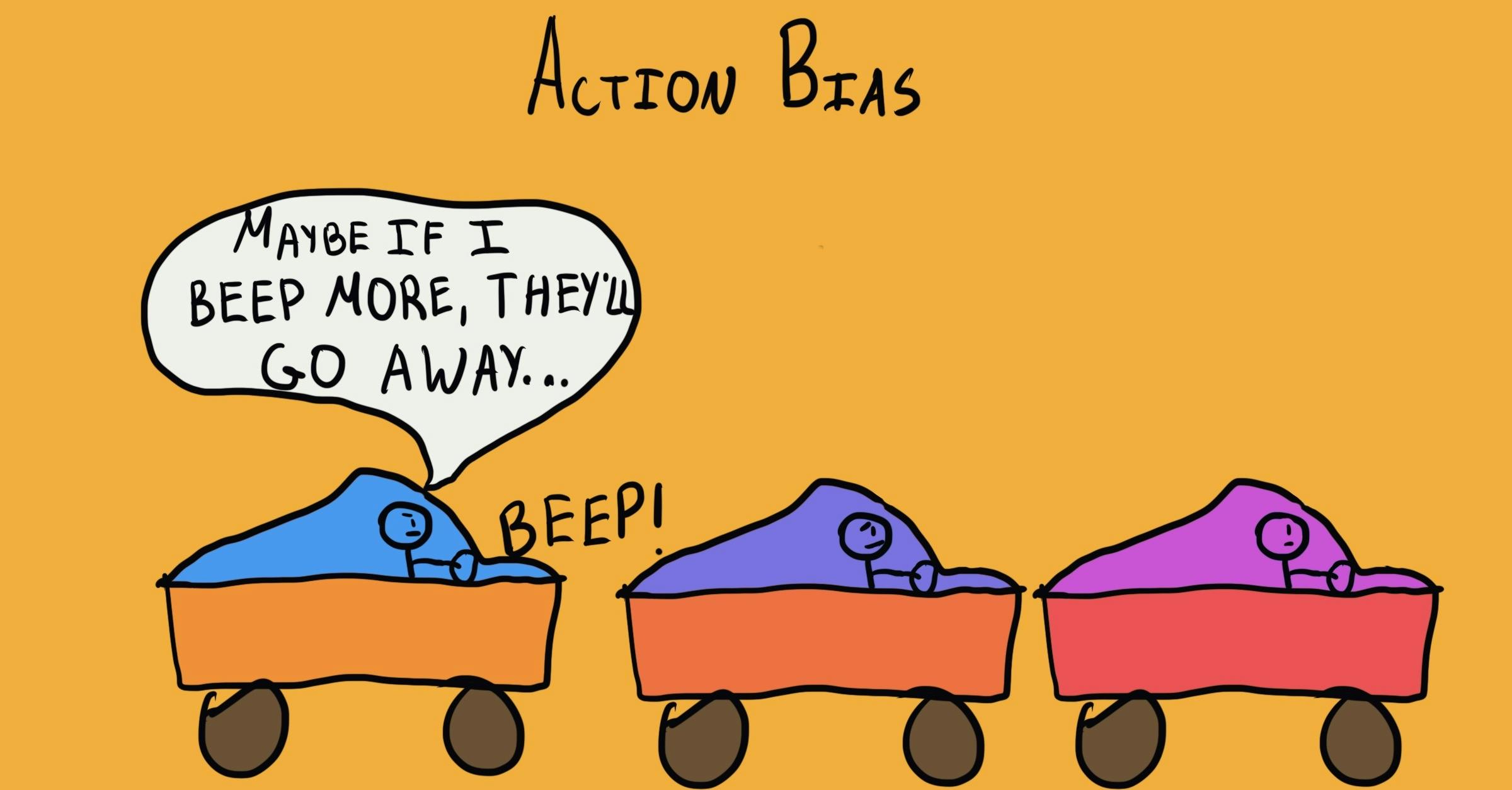

Action Bias

, explained.What is the Action Bias?

The action bias describes our tendency to favor action over inaction, often to our benefit. However, sometimes, we feel compelled to act, even if there’s no evidence that it will lead to a better outcome than doing nothing would. Our tendency to respond with action as a default, automatic reaction, even without solid rationale to support it, has been termed the action bias.

Where this bias occurs

Suppose you’re a soccer goalkeeper, preparing to block a penalty kick in the midst of the final playoff game. If you’re like most goalies, when attempting to stop a shot, you’ll jump either to the left or right nearly every time. Yet your chances of successfully blocking the kick are statistically greater if you simply stay still.1

So what compels you to jump instead of standing your ground? It’s the action bias: our instinct that doing something is better than doing nothing. You may feel that people would judge your failure to make the save less harshly if you could prove that you made an attempt to stop it. Unfortunately, as counterintuitive as it feels, it’s often inaction that increases your odds of success.