Why do we focus more on some things than others?

Attentional Bias

, explained.What is Attentional Bias?

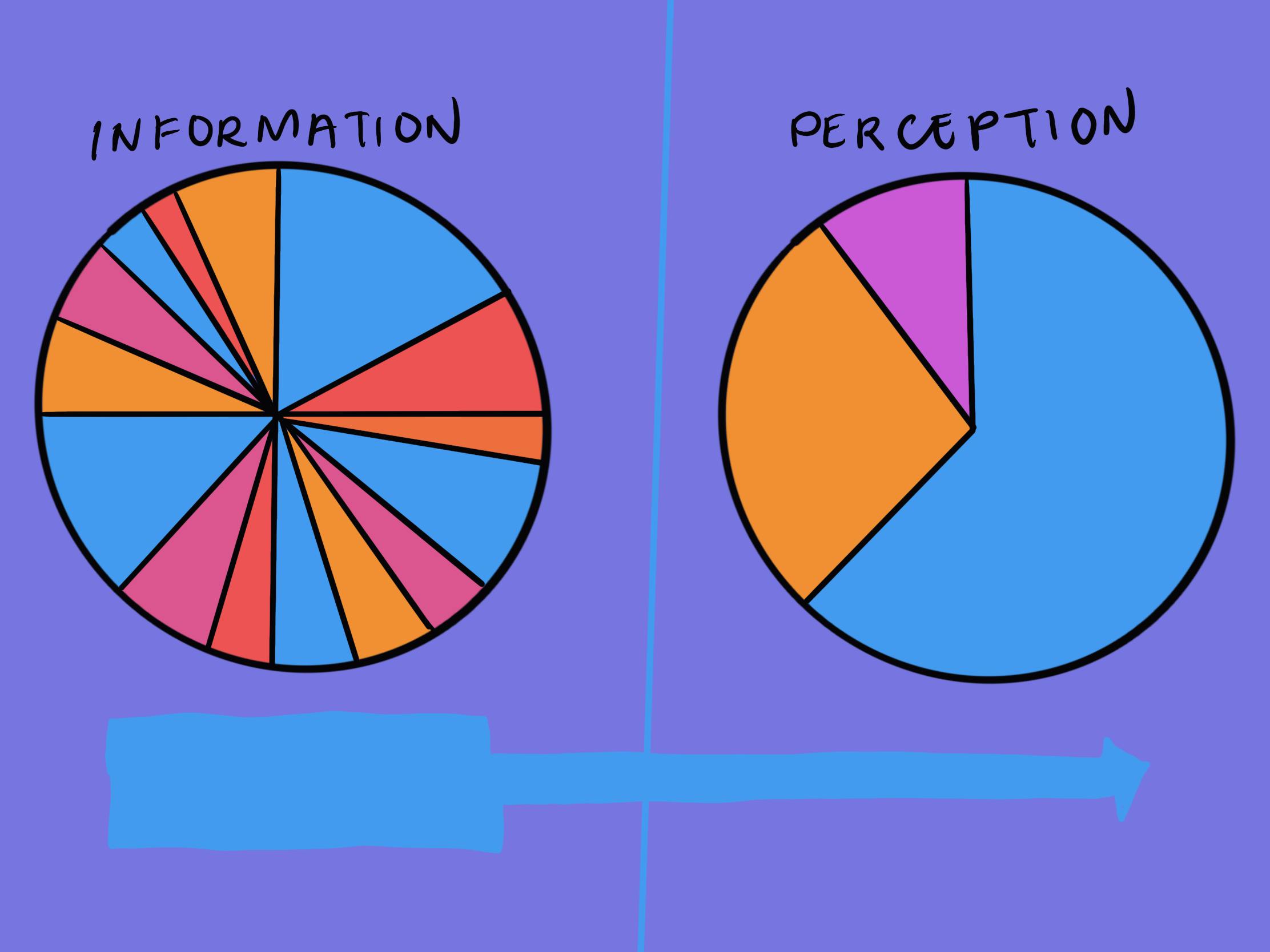

The attentional bias describes our tendency to focus on certain elements of our environment while ignoring others. Research has shown that many different factors can bias our attention, from external events and emotional stimuli (such as a perceived threat to our safety) to internal states (such as hunger or sadness).

Where this bias occurs

Let’s say you want to improve your diet, so you decide to reduce the amount of sugar you eat. To work toward this goal, you resolve to buy fewer desserts when you go grocery shopping. However, one week, you have a particularly busy schedule, and you end up doing your grocery shopping at the end of a work day before you’ve had a chance to eat dinner. You try your very best to take your mind off the junk food aisle, but you can’t seem to stop thinking about your favorite snacks. Eventually, you cave and throw a couple of boxes of cookies into your cart, which you later end up eating.

In this example, the state of being hungry has biased your attention toward foods that can quickly satisfy your energy needs—like sugar—and made it much more difficult for you to follow through on your plan. Attentional bias most often pops up when we’re facing emotionally charged information or stimuli, such as hunger, angry faces, or threatening words. An attentional bias to threat allows us to identify potential dangers in our environment quickly but can make us overly sensitive to what we perceive to be threatening cues in our daily life, even when we are relatively safe.