Pourquoi nous sentons-nous plus concernés par une option après l'ajout d'une troisième ?

Qu'est-ce que l'effet de leurre ?

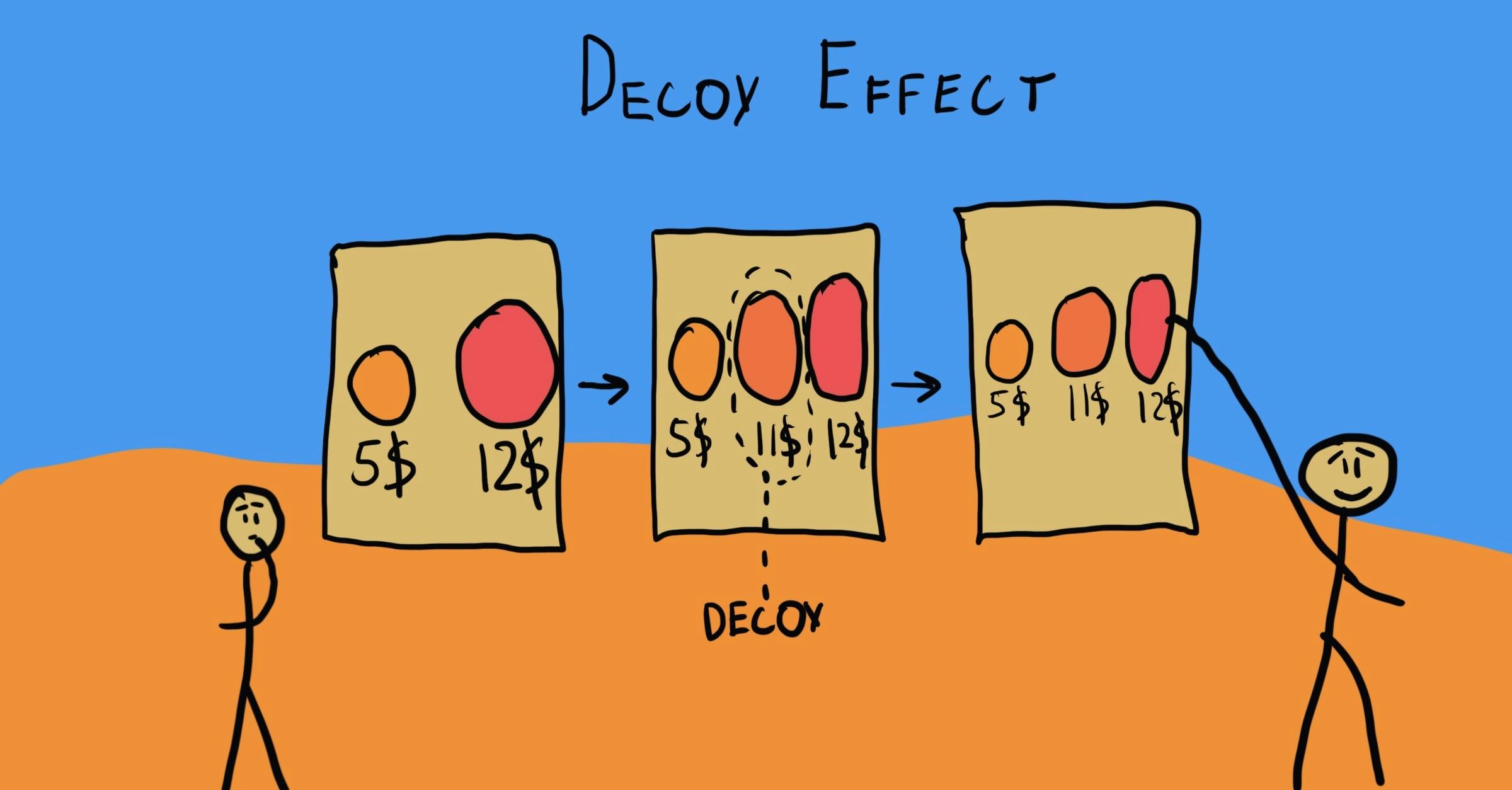

L'effet de leurre décrit comment, lorsque nous choisissons entre deux alternatives, l'ajout d'une troisième option moins attrayante (le leurre) peut influencer notre perception des deux choix initiaux. Les leurres sont "dominés de manière asymétrique" : ils sont complètement inférieurs à une option (la cible) mais seulement partiellement inférieurs à l'autre (le concurrent). C'est pourquoi l'effet du leurre est parfois appelé "effet de dominance asymétrique".

Où ce biais se produit-il ?

Imaginez que vous fassiez la queue dans un cinéma pour acheter du pop-corn. Comme vous n'avez pas très faim, vous vous contentez d'un petit sachet. Lorsque vous arrivez au stand, vous constatez que le petit sac coûte 3 dollars, le moyen 6,50 dollars et le grand 7 dollars. Vous n'avez pas vraiment besoin d'un grand sac de pop-corn, mais vous finissez par l'acheter quand même parce que c'est une bien meilleure affaire que le moyen.

Dans cet exemple d'effet de leurre, nous pouvons considérer le grand pop-corn comme la cible que le cinéma veut que vous achetiez, tandis que le petit pop-corn est son concurrent. En ajoutant le pop-corn moyen comme leurre (puisqu'il ne coûte que 50 cents de moins que le grand), le cinéma vous convainc de céder et d'acheter le plus gros.