Intentionality

The Basic Idea

What does it mean to be human? Is it the bodies that carry us or the minds in our heads? Is it the emotions we feel or the experiences we have? Like most of us, thinking about what it means to be human might send you spiralling down a deep train of thought.

Intentionality refers to the ability of one’s mind to represent something. It is mostly ascribed to mental states, such as perceptions, beliefs, and desires.1 In discussions of the human mind, consciousness and intentionality are often central phenomena. Intentionalism has even become its own area of study.2 Intentionalism, also known as representationalism, refers to the belief that the nature of one’s conscious mental state is determined by its intentionality.3

An unconscious consciousness is no more a contradiction in terms than an unseen case of seeing.

– Franz Brentano, founder of intentionalism and author of Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint

Theory, meet practice

TDL is an applied research consultancy. In our work, we leverage the insights of diverse fields—from psychology and economics to machine learning and behavioral data science—to sculpt targeted solutions to nuanced problems.

Key Terms

Intentionalism: A thesis of intentionality proposed by Franz Brentano in the 19th century.

Phenomenology: A philosophical movement that originated in the 20th century, in which the main objective was the direct investigation and description of phenomena as they were consciously experienced, without theories about their causal explanations or preconceptions.

Intentionality: The characteristic of consciousness, such that human minds can represent things, properties, or states of affairs.

Consciousness: Although varied in its definitions, consciousness can be considered to be an awareness of internal and external existence.

Folk psychology: The study of how humans explain and predict others’ behaviors and mental states.

Executive functioning: A set of cognitive processes that are necessary for intentional behavioral control.

Theory of mind: The ability to think about both one’s own and others’ mental states.

History

Franz Brentano was a 19th century philosopher who believed that philosophical psychology should be done in a rigorous, scientific manner.4 To this extent, scientific methods were those that applied observation and described facts. These beliefs were the driving force behind his seminal 1874 work, Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint.

Part of Brentano’s goal was to lay the basis for a scientific psychology by providing a detailed, scientific characterization of mental phenomena.4 Thus, Brentano proposed a set of criteria to distinguish mental from physical phenomena, with the three most significant criteria being:

- Mental phenomena are the exclusive object of inner perception;

- Mental phenomena always appear as a unity; and,

- Mental phenomena are always intentionally directed towards an object.

Brentano’s third principle introduced intentionality to contemporary philosophy: he believed that the main characteristic of consciousness is that it is always intentional.4 When distinguishing between mental and physical phenomena, mental phenomena require intentionality while physical phenomena will lack intentionality.

Brentano went on to become a professor at the University of Vienna.4 There, he taught Edmund Husserl, one of the founders of phenomenology, which was the study of phenomena as they were consciously experienced.5 Husserl emphasized intentionality as a way to address the relationship between what is within one’s consciousness and what extends beyond it.

Specifically, Husserl proposed that objects themselves are not external, until humans ascribe meaning to them.5 Additionally, given that we operate from a first-person point of view, our conscious reality is defined by our own experiences. Rather than characterizing an experience at the time that we perform it, we look back on prior experiences to inform present ones.

This view of intentionality can be tied into folk psychology, which is the study of how humans explain and predict both the behaviors and mental states of other people by using prior experiences.6 In modern academia, we can find folk psychology within studies of philosophy of mind and cognitive science.

People often will distinguish between others’ intentional and unintentional actions.6 After all, evaluating whether a behavior stems from a purposeful action or accidental circumstances is a key determinant for social interaction. For example, interpreting whether a hurtful comment from a friend was intentional or not will determine one’s response to the statement and its effect on our relationship. These assumptions are known as mindreading.

Since its conceptualization by Brentano in the 19th century, intentionality has varied in its applications. From its adoption by phenomenology in the 20th century to its recent use in the realm of folk psychology, the essence of being purposeful and direct has remained.

People

Franz Brentano

This German philosopher is considered to be the founder of intentionalism, concerned with the acts of the mind rather than the contents of the mind.7 Brentano is most known for his 1874 work, Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint in which he attempted to develop a systematic psychology that would be the science of the soul. Studying the role of mental processes in intentional existence led Brentano to his position as a philosophy professor at the University of Vienna. There, Brentano inspired prominent psychologists and philosophers including Sigmund Freud, Carl Stumpf and Edmund Husserl.

Edmund Husserl

Husserl, another German philosopher, studied under Brentano at the University of Vienna.8 Husserl is the founder of phenomenology, a method for describing and analyzing consciousness using scientific principles. It’s not hard to see Brentano’s influence here, as Husserl often incorporated Brentano’s idea of intentionality into his phenomenological work. Husserl’s background in mathematics helped him draft the outline of phenomenology as a universal philosophical science.

Consequences

Extending on ideas from folk psychology, attribution theorists have emphasized intentionality for its role in social perception.9 After all, perceiving intentionality can influence other psychological processes such as aggression, blame, and punishment.

In 1958, Austrian psychologist Fritz Heider developed his model of intentional action, by recognizing intention as the central factor in personal causality.9 Heider emphasized how one’s interpretation of the causes of a behavior (i.e. whether they were intentional or not) will reflect their pre-existing beliefs about the other actor’s mental states and motivations. In this model, Heider distinguished between beliefs regarding one’s ability and beliefs about whether one was “trying” or not. He further broke it down into critical intention (what a person is trying to do) and exertion (how hard the person is trying).

Developed in the 1960s, the Theory of Reasoned Action and Theory of Planned Behavior have focused on how attitudes shape intentions, which can subsequently shape actions.11 These models have been used to explain the intention-action gap, which occurs when one’s values, attitudes, or intentions don’t match their actions. In these models, one’s attitudes and subjective norms will influence one’s intentions to perform a behavior. For example, students who value academic achievement and always doing the best that they can do, will be more likely to focus on their studies. On the other hand, students who believe “Cs get degrees” will lack motivated intentionality, and be less likely to study hard.

Intentionality has also been an area of focus in developmental psychology, as it contributes to success in social situations. Understanding the intentions of others’ behaviors is important for communication and achieving cooperative goals.12 Developmental psychologists often consider intentionality, specifically theory of mind, as a prerequisite for higher-level understanding.13 Theory of mind is the understanding that people’s actions are caused by internal mental states, such as their beliefs, desires, and intentions. Once theory of mind develops, we understand that people do things both because they want to and know how to.

Even as young as 6 months old, infants demonstrate imitation and observational learning10 Impressively, infants will analyze the credibility of a person and evaluate their intentions behind a behavior. For example, when imitating an adult’s behavior, they will imitate what was intended rather than what was actually done. This form of intentionality greatly increases children’s abilities to learn from others.

Executive functioning is an overarching term used in cognitive and developmental psychology that is linked to theory of mind.13 Executive functioning is used to describe cognitive processes that are important for planning and executing intentional actions. An important set of mechanisms key to executive functioning are short-term and working memory, which allow us to keep limited bits of information active and available for guiding our intentional actions.

Based on the relationship between intentionality and attributions, it is evident that intentionality plays an important role in our behavioral decisions.14 In fact, intentions have been found to be a necessary precondition for decision making, as they help us define problems and guide the search for alternatives. It can therefore be argued that deliberate action planning consists of more than decision making alone: before making a decision, we must choose what to decide.

Controversies

Over time, intentionality has been applied to a variety of fields. Even within the fields of philosophy and psychology, interpretations of intentionality and consciousness have differed. For example, Brentano’s original work on intentionalism focused on distinguishing between mental and physical phenomena.4 However, phenomenology shifted the definition of intentionality to fit their predominant focus on consciousness.5 In psychological works, intentionality then becomes a paramount framework in studies of cognitive and social processes.12,13

Intentionality has been incorporated into a variety of fields, raising a new problem. Understandings of intentionality get confused, even in terms of whether people use “intentionality” to reference agency or desire.15 Even if there was a clear understanding of the different interpretations of intentionality, there are still critiques of the original theories.16

Husserl, for example, revitalized intentionality by adapting it to phenomenology.16 The goal of phenomenology is to focus on observable phenomena, rather than making speculations.5 Yet, Husserl insisted that consciousness is dependent on being phenomenological.17 Critics argue that for Husserl to state that all of consciousness is rooted in observable phenomena, when consciousness itself is inferred, is both speculative and circular reasoning. To this end, Husserl’s adaptation of intentionality has been criticized for its logical gaps.

Critics of folk psychology have questioned whether the mechanisms used for a general understanding of others’ actions can fulfil the requirements of the scientific method.18 It is argued that concepts used in folk psychology like intentionality, mindreading, and theory of mind are not scientific.

Case Study

Failed action limitation paradigm

When imitating an adult’s behavior, infants will imitate what was intended rather than what was actually done.10 But what exactly does this mean? American psychologist Andrew Meltzoff wanted to know what age children started to assess intentionality.19

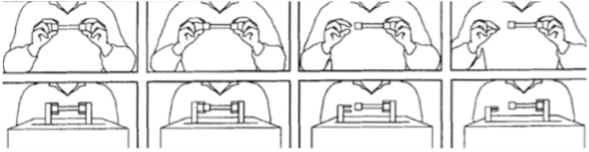

In a well-known and often cited study from 1995, Meltzoff showed 18-month-old children an adult performing unsuccessful acts.19 For example, the adult held a tube as pictured in the top row. Despite trying to pull off the cap on one side of the tube, the adult’s hand kept slipping. The adult demonstrated this failed action a few times, before the children were allowed to try. If children understood the adult was trying to pull off the cap, they would try to do that too. Indeed, 60% of 18-month-olds attempted the failed action.

However, when the adult was replaced with a machine (as pictured in the bottom row), only 10% of the children attempted the failed action.19 This difference suggests that children are much more likely to make goal-to-action interpretations when observing an adult, suggesting they can assess an actor’s credibility.10 Clearly, children as young as 18 months are aware of the differences between humans and machines, such that intentionality can be ascribed to human behaviors, but not to machines.19 This also suggests that theory of mind can begin developing from an early age.13

Motivated learning

Gamification techniques have recently become a popular educational strategy.20 An example is awarding virtual badges after watching certain video lessons or completing a set of exercises. Applying learning analytics to gamified environments has given educators useful information about student motivation, but they do not tell us much about intentionality.

A team of Spanish researchers set out to analyze student intentionality through badge achievement on the popular online platform, Khan Academy.20 The researchers utilized two different types of badges: topic badges and repetitive badges. Topic badges required students to reach a proficient level in a set of exercises to earn the badge, while repetitive badges were awarded to students who kept solving exercises after they had already achieved proficiency.

Intentionality for topic badges was calculated using an algorithm which assessed the maximum number of badges that students could have received, given the number of exercises that they mastered. It did this by dividing the number of earned badges by the maximum number possible in that set.20 On the other hand, intentionality for repetitive badges was calculated through the percentage of badges that were earned once mastery had already been achieved.

After assessing 291 university students, the researchers found that they did not show much interest in earning badges, despite having a large percentage of students who spent at least 60 minutes on exercises.20 However, there was notably more interest in repetitive badges than new topic badges, with 39.52% of users earning repetitive badges intentionally. While students generally showed higher motivation for earning repetitive badges, repetitive badges may have been easier to earn, relative to mastering a new topic.

Knowing which badges students are most motivated by can be useful for educators who are structuring the learning process in a virtual environment.20 The researchers suggest that other platforms should implement badges to motivate intentional learning. More specifically, topic badges should be awarded when proficiency is reached on a set of predefined exercises. When it comes to repetitive badges, platform designers should carefully consider the utility and effectiveness of offering repetitive badges, if students have already mastered the topic. Perhaps motivation reallocated toward new material could bolster students’ learning.

Related TDL Content

Nudging consumers towards big-picture thinking

Considering the role of intentionality in theory of mind, does this intentionality separate us from animals? Moreover, can theory of mind nudge us toward thinking long-term and into the future? Take a look at this article to understand how theory of mind can be thought of as the “theory of me.”

Sources

- Intentionality. (2019, February 8). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://seop.illc.uva.nl/entries/intentionality/#InteExhiAllMentPhen

- Chalmers, D. J. (2004). The representational character of experience (pp.153-181).

- Crane, T. (2007). Intentionalism.

- Franz Brentano. (2019, January 30). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/brentano/

- Phenomenology. (2013, December 16). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/phenomenology/

- Folk Psychology as a Theory. (2016, august 16). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/folkpsych-theory/

- Franz Brentano. (2021, March 13). Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Franz-Brentano

- Landgrebe, L. M. (2021, April 23). Edmund Husserl. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Edmund-Husserl/

- Malle, B., & Knobe, J. (1997). The folk concept of intentionality. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 33, 101-121.

- Siegler, R., Eisenberg, N., DeLoache, J., Saffran, J., & Graham, S. (2014). How Children Develop. Worth Publishers.

- Montaño, D. E., & Kasprzyk, D. (2008). Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, & K. Viswanath (Eds.), Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 67–96). Jossey-Bass.

- Zelazo, P. D., Astington, J. W., & Olson, J. W. (1999). Developing Theories of Intention: Social Understanding and Self-Control. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Bjorklund, D., & Causey, K. (2017). Children’s Thinking: Cognitive Development and Individual Differences. Sage Publications.

- Kesting, P. (2006). The meaning of intentionality for decision making. Available at SSRN 887088.

- Dennett, D. C. (1989). The Intentional Stance. MIT Press.

- Morriston, W. (1976). Intentionality and the phenomenological method: A critique of Husserl’s transcendental idealism. Journal of the British Society of Phenomenology, 7(1), 33-43.

- Duranti, A. (1993). Truth and intentionality: An ethnographic critique. Cultural Anthropology, 8(2), 214-245.

- Fletcher, G. (1995). The Scientific Credibility of Folk Psychology. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Meltzoff, A. N. (1995). Understanding the intentions of others: Re-enactment of intended acts by 18-month-old children. Development Psychology, 31(5), 838-850.

- Ruipérez-Valiente, J. A., Muñoz-Merino, P. J., & Kloos, C. D. (2016). Analyzing students’ intentionality towards badges within a case study using Khan Academy. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Learning Analytics & Knowledge (pp. 536-537).