Evolutionary Change

The Basic Idea

Imagine spending your days foraging for food, preying after wild animals and collecting wild plants. Instead of a fixed home base, you constantly move to new places where more resources will be available. While this lifestyle may seem strange to you, people who lived like this – hunter-gatherers – are considered humanity’s first and most adaptive population.1 This means that hunter-gatherers formed such lifestyles in accordance with their environments, in order to improve their chances for survival and reproductive success. In fact, there are still some contemporary societies that follow hunter-gatherer practices, although with some modifications.

The concept of adapting behavior to one’s environment is a core feature of evolution, which describes changes in the inherited traits of a population through successive generations.2 When living organisms reproduce, they pass on successful traits: traits that ensure their survival and ability to reproduce. These inherited traits, as well as new adaptations that result from changing environments, influence subsequent generations’ survival and behaviors. Applying an evolutionary lens to human behavior, we can understand the mechanisms and drives that underlie many behaviors, as well as the environmental conditions through which they became common.

It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but the ones most responsive to change.

– Charles R. Darwin, creator of evolutionary theory and author of On the Origin of Species

Theory, meet practice

TDL is an applied research consultancy. In our work, we leverage the insights of diverse fields—from psychology and economics to machine learning and behavioral data science—to sculpt targeted solutions to nuanced problems.

Key Terms

Adaptation: Changes in the behavior, physiology, and/or structure of an organism to better suit its environment. Successful adaptations lead to evolution.

Human behavioral ecology: The study of the evolutionary basis for behavioral interactions between individuals. It shows how competition and cooperation between and within species can affect evolutionary fitness.

Evolution: Changes in the characteristics of a species over several generations.

Evolutionary fitness: How well a species is able to survive and reproduce in its environment.

Natural selection: The idea that advantageous characteristics and adaptations that contribute to survival will persist across generations, while disadvantageous characteristics will die out.

History

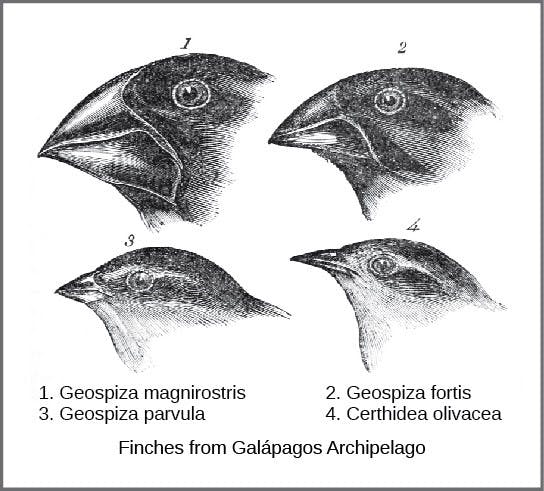

English naturalist Charles R. Darwin spent the years 1831 to 1836 travelling around the world, visiting South America, Australia, and the southern tip of Africa.2 Darwin stopped at several island chains, documenting patterns in the distribution and features of organisms. Upon arrival at the Galápagos Islands, Darwin observed several species of organisms across the islands that seemed similar, yet had distinct differences. Specifically, he noticed that each of several finch species had different beak structures that seemed to fit the demands of their environment. For example, the finches that ate large seeds tended to have large, tough beaks, while those that ate insects tended to have thin, sharp beaks. Additionally, the finches on the Galápagos Islands were similar to species on the nearby mainland of Ecuador but different from those elsewhere.

Based on his observations, Darwin theorized that the island species were all modified versions of the original mainland species, which conceptualized the mechanism of natural selection.2 Darwin argued that natural selection was the outcome of three principles in nature: (1) that characteristics of organisms are inherited; (2) that resources for survival and reproduction are limited, resulting in competition for resources in each generation; and (3) that offspring inherit variations in characteristics. Since resources are limited and different characteristics are inherited, the only offspring with advantageous characteristics would be successful in their quest for those resources, which would allow their traits to be better represented in subsequent generations. Ultimately, natural selection results in evolutionary changes. Darwin’s theory and arguments for evolution by natural selection were published in his 1859 book, On the Origin of Species.

Later in 1873, Darwin argued that human emotional expressions likely evolved in similar ways as physical features. He believed that emotional expressions served a communicative purpose, so humans and primates had an innate, universal set of expressions. Specifically, those more adept at expressing and communicating their emotions were more likely to survive and therefore more likely to pass on this valuable trait. He explored such ideas in his 1872 book, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, which had a significant influence on the early development of psychology. The history of evolutionary theories could not possibly be told without detailing the advancements made by Darwin.

People

Charles R. Darwin

Born in 1809, Darwin was an English naturalist whose theory of evolution by natural selection became the foundation for contemporary evolutionary studies.3 Although controversial among religious Victorian society for his suggestions that animals and humans shared a common ancestry, Darwin’s work appealed to the rising class of professional scientists. By the time he passed away in 1882, evolutionary theory had spread across political, literary, and scientific domains.

Consequences

Paving the way for subsequent research related to human and animal changes, Darwin’s evolutionary theory has become a cornerstone of biology, psychology, and sociology. It has also influenced the way we think about the world today, in regard to genetics and survival. One example is societal conceptions of diversity: a diverse population is necessary to sustain the processes of natural selection. Diversity, then, should be celebrated and embraced by society, as it is actually beneficial for everyone’s survival. While evolutionary theory continues to be studied and researched, it has also influenced three important research domains: behavioral ecology, human behavioral ecology, and comparative cognition.

Behavioral ecology studies the evolutionary basis for animal behavior due to ecological pressures, also known as interactions with the environment.4 Dutch biologist Nikolaas Tinbergen recognized the importance of adaptation and evolution as per Darwin’s theory, but he also believed that animal behavior should be analyzed in terms of four separate causes, each of which could be framed as a scientific question:

- What is the function of the behavior?

- How did the behavior develop across evolution and how does it compare to the behavior of closely related species?

- How does the behavior change across the lifespan of the organism?

- What are the internal mechanisms that produce the behavior?

The first two questions are ultimate causes of behavior, which focus on evolutionary lineage and ecological pressures that influence reproductive success and survival explained in terms of adaptive value. To this end, Darwin’s theory was incredibly influential on behavioral ecology. However, the latter two questions are proximate causes and consider additional factors, explaining animal behavior in terms of development.

As behavioral ecology emerged from Tinbergen’s work, researchers were interested in the mechanisms specific to human behavior. As a result, human behavioral ecology (HBE) was developed to apply the principles of evolutionary theory to the study of human behavioral and cultural diversity.5 HBE examines the adaptive design of human traits with the goal of determining how environmental factors shape behavior flexibility. HBE attempts to explain behavioral variations as adaptive solutions to the competing demands of human growth, development, mate acquisition, reproduction, and parental care. For example, the theory of reciprocal altruism posits that one individual will provide benefits to another, with the expectation of reciprocation in the future.

Additionally, some scientists felt a need to integrate cognitive psychology into behavioral ecology, to better understand the relationship between behavior and natural selection pressures.6 As a result, comparative cognition became the comparative study of the cognitive mechanisms in various species.4 Scientists must systematically compare cognitive abilities between both closely and distantly related species to better understand cognitive function across them. Such analyses can help determine which selection pressures led to differing cognitive abilities.

Controversies

Despite the mass awareness of evolutionary theory and scientific research on the topic, Darwin’s work does not come without its criticisms. Even today, the legitimacy of evolution is hotly debated, with most criticism coming from religious groups, specifically relating to creationism. Broadly, creationism is the belief that nature, and aspects such as human life, Earth, and the universe, were created by a god.7 To this end, creationists believe that evolution is religious, rather than scientific. Some feel that by accepting evolution, one is rejecting religion and promoting atheism. Such beliefs rest in an “anti-evolution movement and attack the teaching of evolution.8

The controversy surrounding evolution has historically extended into the American education system.8 Many favored the teaching of evolution in public schools, valuing contemporary scientific thinking, freedom of speech, and the separation of church and state. Alternatively, those opposed to teaching evolution felt it was supporting eugenics and religiously inaccurate narratives. The controversy over implementing evolution into the education system became a legal issue in the late 1960s, when the U.S. Supreme Court struck down state laws banning the teaching of evolution in public schools. Specifically in the famous legal case Epperson v. Arkansas,9 it was said that the law violated students’ abilities to learn from a non-Christian viewpoint, thus promoting religion. Despite an accumulation of legal activity, there remains debate today over whether evolution should be taught in schools.

In response to religious criticisms, authors like Robert Asher (Evolution and Belief: Confessions of a Religious Paleontologist) explore the overwhelming evidence for evolution and explain why it should not be perceived as a threat to the Christian faith.10 While the Catholic Church now recognizes the existence of evolution,11 the creationism versus evolution debate remains controversial and popular, as seen in this debate between Christian author Ken Ham and scientist Bill Nye.

Generally, critics state that evolution cannot be taken as fact. However, scientific facts are verifiable empirical observations for which there is overwhelming evidence, and the theory of evolution is indeed well-established.12 13 Despite criticisms from the public, then, evolution is widely accepted by scientists. If anything, most general criticisms toward evolution are often based on misunderstanding.14 15 For example, one common argument is, “If humans descended from monkeys, why are there still monkeys?”16 17 The answer is that evolutionary theory would say humans and monkeys have a common ancestor, rather than say that humans are descendants of monkeys. Secondly, some mistakenly believe that evolution results in the extinction of previous species. However, species develop new traits and behaviors, changing their genetic makeup, rather than going extinct. Although the term evolution rings a bell for most people, the extent of their familiarity varies, and such inconsistencies are often the root of criticisms from the general population.

Case Study

Gossip in group environments

Gossip tends to have a negative connotation attached to it, despite its prevalence in social situations. From an evolutionary perspective, there is a strong case that language evolved to facilitate bonding of large social groups, giving people the advantage of exchanging information outside of their immediate environments.18 However, language also serves four other evolutionary purposes: (1) to seek advice; (2) to control others to abide with social agreements; (3) to advertise ourselves; and (4) to deceive. Knowing this, gossip has been proposed to be advantageous to society and crucial for the evolution of larger social groups.

Spanning across three semesters, a 2010 study assessed the ways in which self- and group-serving gossip functioned.19 During the first semester, part of the team suffered at the expense of a social loafer whose low commitment to the team impeded the rest of the group’s success. This dynamic often exists in work environments but is especially impactful on a rowing team that depends on full physical coordination. The researchers found that rowers gossiped at significantly higher rates when confronted with the topic of the loafer than during the other two semesters when the talk centred on neutral subjects. Additionally, the gossip increase included both negative gossip about the loafer, but also positive gossip about the other hard-working members on the team. Thus, the findings imply that members of a group would spend time reinforcing positive group-serving norms when threatened by the behavior of an individual violating said norms. In other words, team members used gossip to enforce and maintain group-serving norms. While gossiping can certainly have negative effects, such as for the subject of gossip, research also shows its advantage in bringing people together and being a measurement for the strength of the connection.

Intrasexual competition within workplaces

Referring to rivalry between members of the same sex, intrasexual competition holds that same-sex rivalries are motivated by limited access to potential mates.20 Darwin recognized the importance of intrasexual competition and suggested that it leads to important behavioral adaptations for attracting mates, as well as obtaining the necessary resources for reproduction and offspring care. Importantly, evolutionary theory holds that females have to invest more than males do for sexual reproduction, so they are considered a scarce resource over which males compete. To this end, intrasexual competition is more common between males than females.

Workplaces are important domains for intrasexual competition among males, as they boast qualities naturally selected for, such as status, prestige, and resources. Although women can be in competition with men in the workplace, evolutionary theory holds that men are more likely to perceive other men as their primary competition. Indeed, a study by Steil and Hay sampled heterosexual men and women with prestigious roles in male-dominated fields, such as law and investment banking, and showed that choice of comparison target was determined by sex and partially income.21 Women were significantly more likely to make opposite-sex comparisons than men, and the higher a woman’s income was, the more likely she was to compare her professional accomplishments predominantly to men’s. On the other hand, men showed the opposite effect: the higher their income, the more likely they were to compare themselves to other men. Such findings are consistent with the expectations of evolutionary theory, that intrasexual competition is more likely to occur in males and is based on status and resources.

Related TDL Content

Need, Not Greed: Bonuses, Risk-Taking and Evolution

Have you ever surprised yourself by taking a risk, or thought others to be greedy based on their impulsive actions? If so, take a look at Belinda Vigors’ article applying an evolutionary approach to humans’ needs. As it turns out, it’s less so that we’re greedy, and more that we have certain needs to fulfill.

’Tis the Season: The Science of Saying Thanks

“Thank you” – two little words we use constantly, sometimes without much thought or effort. Some might even say it’s an automatic response – evolutionary theory has an explanation!

Sources

- Lee, R. B., & Daly, R. (1999). The Cambridge encyclopedia of hunters and gatherers. Cambridge University Press.

- Malmquist, S., & Prescott, K. (2010). The genetic basis of evolution. In Human biology. Simple Book Publishing.

- Desmond, A. J. (2021, March 1). Charles Darwin. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Charles-Darwin

- Olmstead, M. C., & Kuhlmeier, V. A. (2015). Comparative cognition. Cambridge University Press.

- Cronk, L. (1991). Human behavioral ecology. Annual Review of Anthropology, 20, 25-53.

- Yoerg, S. I. (1991). Ecological frames of mind: The role of cognition in behavioral ecology. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 66(3), 287-301.

- Scott, E. C. (2008). Evolution vs. Creationism: An introduction. ABC-CLIO.

- Berkman, M., & Plutzer, E. (2010). Evolution, creationism, and the battle to control America’s classrooms. Cambridge University Press.

- Moore, R. (1999). Creationism in the United States: IV. The aftermath of Epperson v. Arkansas. The American Biology Teacher, 61(1), 10-16.

- Asher, R. J. (2012). Evolution and belief: Confessions of a religious paleontologist. Cambridge University Press.

- Welsh, T. (2014, October 38). Pope Francis says science and faith aren’t at oods. U.S. News. https://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2014/10/28/pope-francis-comments-on-evolution-and-the-catholic-church.

- Coyne, J. A. (2009). Why evolution is true. Oxford University Press.

- Gould, S. J. (1981). Evolution as fact and theory. Discover, 2(5), 34-37.

- Sanders, M., & Makosta, D. (2016). The possible influence of curriculum statements and textbooks on misconceptions: The case of evolution. Education as Change, 20(1), 1-23.

- Kampourakis, K. (2010). Students’ “teleological misconceptions” in evolution education: Why the underlying design stance, not teleology per se, is the problem. Evolution: Education and Outreach, 13(1), 1-12.

- Willis, P. (2011, October 4). If evolution is real why are there still monkeys? ABC Science. https://www.abc.net.au/science/articles/2011/10/04/3331957.htm

- Mendes, F. (2017, September 26). If we evolved from apes, why are there still apes? Indiana University. https://blogs.iu.edu/sciu/2017/09/26/why-are-there-still-apes/

- Dunbar, R. I. M. (2004). Gossip in evolutionary perspective. Review of General Psychology, 8(2), 100-110.

- Kniffin, K. M., & Wilson, D. S. (2010). Evolutionary perspectives on workplace gossip: Why and how gossip can serve groups. Group & Organization Management, 35(2), 150-176.

- Buunk, A. P., Pollet, T. V., Dijkstra, P., & Massar, K. (2011). Intrasexual competition within organizations. In Evolutionary psychology in the business sciences (pp. 41-70). Springer.

- Steil, J. M., & Hay, J. L. (1997). Social comparison in the workplace: A study of 60 dual-career couples. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(4), 427-438.