Smart Giving for a Cognitively Saturated World: Nick Fitz and Ari Kagan

We see lots of people asking “Where can my money do good? Where can I actually help?” One of the things that we’ve spent a lot of time thinking about at Momentum was actually helping people understand which organizations are doing great work … and so, we’re trying to help people actually sort through the [choice overload], since there are so many different options. And I think that applies not just to giving but to all of the ways you can engage, whether it’s volunteering, whether it’s posting on social media, or whether it’s calling people to get out the vote. There are so many different options, and I wonder whether maybe a sense of powerlessness comes from the lack of clarity around what you should do. “What is my responsibility? What is enough? What is going to work?”

Intro

In this episode of The Decision Corner, we discuss giving, incentives, and the ethics of behavioral science with Ari Kagan and Nick Fitz, the co-founders and executives at Momentum. Momentum is a charity that ties donations to everyday choices. For example, every time Donald Trump tweets, the app will have you automatically donate 10 cents to civil rights and racial justice groups. Nick and Ari have extensive research experience in behavioral science. They both held senior positions at the Center for Advanced Hindsight at Duke University before starting up their donation company.

Topics mentioned in this episode include:

- How to make our daily activities contribute to making the world the kind of place we want it to be

- The consequences of evolutionary change on our cognitive system, especially with respect to social connection and meaning-making

- The feeling of power versus the real thing, and what that has to do with choice overload bias

- Utilitarianism and the role of fairness in donation decision-making

- Samantha, Baby Jessica, and the problems of personalized donations

- Stalin’s insight on donation psychology

- The twin problems of paternalism and finding the right decision-makers

The conversation continues

TDL is a socially conscious consulting firm. Our mission is to translate insights from behavioral research into practical, scalable solutions—ones that create better outcomes for everyone.

Key Quotes

The Difficulties of Donating in a Modern World

“We actually are incredibly powerful right now, right? I mean, there’s a thousand different causes that you could donate your money to, there’s a thousand different ways that you could support and fight back. And that actually makes it harder, because if there’s only one or two things we could do, if we were just dealing with climate change, then it would be, “All right, let’s all just make sure everyone does this one thing.” But suddenly, when you’re dealing with, “How do we fight back against police brutality? And also, how do we deal with the fact that Trump is trying to destroy democracy, and how do we deal with the fact that the environment is on fire and there’s 40 different ways to do each of these things?” I think you can then feel a little bit lost.”

The Problem of Traditional Giving

“That connection as a recurring donor feels so transactional, right? You sign up for this monthly donation, and maybe you get a letter if you’re lucky. A lot of them might just send you a tax receipt in an email, and then you’re done, and then you just get this drain in your bank account month to month. This feels like a utility bill. And I think trying to figure out how to help donors actually connect with the charity, feel like they’re a part of that narrative, is one of the big things we’ve struggled with Momentum. It’s been one of the big inspirations for what we’re doing. What we really want to do is help people have that frictionless option of recurring donations, have it set up so they don’t have to keep deciding over and over again to make that decision to support, but still feel that tie, still feel that connection to what the charity is doing, and to their own life?

On the Consequences of Evolutionary Psychology

“When we were evolving, we saw the same 150 people around us all the time, and the evolutionary rewards with helping people in your community, because then they’ll help you back. And sending your dollar overseas wasn’t even possible, let alone certainly wouldn’t have the social benefits that would be more likely to pass on your genes to your children. Right? And so, we end up with all of these biases that predispose us towards helping a certain subset of people who are close to us, who look like us, who are familiar, and we’re comfortable with, who have a better story, who happen to catch our attention, who we are emotionally connected to.”

On Behavioral Science

“Behavioral science ends up mapping or illuminating ways in which we don’t align with our values.”

Transcript

Brooke: Hello everyone, and welcome to the podcast of The Decision Lab, a socially-conscious applied research firm that uses behavioral science to improve outcomes for all of society. My name is Brooke Struck, research director at TDL, and I’ll be your host for the discussion. My guests today are Nick Fitz and Ari Kagan, co-founders and executives at Momentum. In today’s episode, we’ll be talking about behavioral science and empowerment. How do we nudge people towards building the world they want and getting a sense of meaning? Nick and Ari, thanks for joining us.

Nick: Thanks for having us.

Ari: Excited to be here.

Brooke: All right, let’s dive right in. Tell us all about Momentum. I hear that this is a platform for empowerment. How does it work? What does it do?

Ari: Yeah, an automatic donation platform that ties giving to the things in donors’ daily lives. In particular, what we do is we set up automatic donations based on the things you’re doing or the things you care about. For example, when you go out to eat, you might add 10% of the bill, and move that to a hunger charity. Or every time you protest, you might donate for every step you take to Black Lives Matter. Or when Trump tweets, you could donate 10 cents to stop his reelection. And these automatic donation rules run in the background based on the way that you’ve set them up, so that you can support the organizations and the causes that you care about without having to do work over and over again to decide to actually re-support those great causes.

Nick: Yeah, I think I will just say, I’m curious, Brooke, what you mean by empowerment. So, certainly, we tie giving to what people do, and in that way, I think people feel connected to the change that they make and also to their values or their identity. But yeah, I’m super curious to learn a bit more about when you say empowerment, what you mean.

Brooke: You mustn’t turn the tables on the interviewer. This is unfair. Yeah. I mean, now that you prod me a little bit, one of the things that I think on the topic of charitable giving is that, for a lot of us, we don’t see our professional work, the stuff that we spend the majority of our waking hours doing, as necessarily contributing to the world that we want to live in, that for a lot of us contributing to building that ideal is something that unfortunately gets relegated mostly to the margins of our lives. It’s not the majority of the time that we spend, it’s not the majority of the energy that we spend, it’s not the majority of the money that we spend. So, charitable giving, and I think Momentum is a good example of this, is trying to help us to have opportunities to at least increase that margin, and in your case, using behavioral science to make that margin easier to access.

Nick: Yeah, that’s super interesting. I think there is something here in that we know people want to give about two and a half times more than they currently do, or at least that came out of some work that we did together back at Duke. And I think, in that way, aligning how people would like to live with how they actually live certainly helps. I think people feel that it unlocks, or it makes it easier for them to give and get up to that, how they’d like to be doing this.

Nick: The example Ari gave is a really interesting one about when you protest, you give. That’s really tied in to this sense, right? Or tying our donations to acts that we do radiates that I donate when I get a friend to get a mail-in ballot or that kind of thing. Or maybe I donate based on the change I want to see in the world. So, I give when an org that we support reverses an overdose, and they get more money and they reverse an overdose. And so, I think feeling really tied into that impact that you’re getting at, that we normally don’t in our lives. Of course, we’re separated from that, generally. Yeah, it’s certainly an effect, I think, that comes out of what we’re building, not even necessarily the main thing we’re trying to get at.

Ari: You have this sense of frustration about so many things going wrong in a world. I mean, I think you normally feel this, let alone take a look at 2020 and the apocalypse, you have to try not to find something that you’re reacting to or feeling helpless about. And so, I think one of the nice things about Momentum is we can take those feelings of helplessness, we can take those feelings of frustration, and actually tie a donation to those moments, to actually push back on the thing that was causing it.

Ari: If you’re looking at the Martian landscape of the orange sky we’ve got here in the Bay Area right now and feeling frustrated about climate change, we can tie a donation to that. We can help you every time you get annoyed about Trump, make a donation to try and stop Trump, right? We can integrate the solution into those moments of powerlessness.

Brooke: Let’s dig into this idea of powerlessness. Why do we seem right now to be so desperately craving meaning, identity, a sense of contribution to a better world? What is it that drives us to have those feelings in the first place?

Nick: I’m not sure that it’s particularly right now. I think things are very salient, or as our attention on it is just opening out here, in particular in California. But I think it’s actually a pretty core psychological need when you think about the hierarchy that way, that helping others is so core to who we are, actually, and there’s some work.

Nick: There’s lots of things that tie into this. It makes me think about an old paper that Dave ran and his team put out on cooperation being intuitive. I think right now, it’s on people’s minds, of course, because it’s also in the news and we also live in a world that there’s a 24/7 news cycle. But I think people have been trying to help people for as long as we’ve been around.

Brooke: And do you feel that there’s a connection between the sense of connection between people and the sense of identity and a sense of meaning-making?

Ari: Yeah. I mean, I think we’ve certainly constructed a world that’s less and less connected to each other. In some ways, it’s more and more connected, right? We now have lights and we now have Facebook and we now have the ability to sit here on a podcast and talk via Zoom, which is incredible.

Ari: In other ways, we now sit in cubicles all day in our offices, right? We now come home to our partners and we go to our house and that might be it, and certainly, even more so during COVID, when you really just shouldn’t be around other folks but the modern world is very work-oriented, very individualistic, especially in Western cultures. The difference between that and the kinds of environments we evolved and the kinds of environments where we have developed our desire to operate and our desire to help each other, we’re living in communities where we’re outside on the streets, we’re seeing the same 30 folks every day of the week, and that’s a little bit different than the world we live in now. And so, I think that isolation and separation from that communal element has benefits and has costs. I think one of those costs is that you then end up feeling that isolation, you end up feeling that lack of connection, and I think that might be a source of some of that as well.

Brooke: You raised an interesting paradox that, in one sense, we’ve never been more connected, and yet, the feeling of loneliness seems so much stronger now than we’ve ever recorded before, certainly in terms of data-gathering. There’s another paradox that I’ve encountered as well, which is, in this pandemic situation where we’re all locked up in our houses and told not to see each other, there have been some anecdotal reports that, in fact, under those strenuous conditions, the opportunities that we have had to help other people have made some people feel more connected to their neighbors than they have in years. What does that tell us about human behavior? And I wonder whether there are some similar notes that you might have encountered in your work with Momentum. What are the behavioral determinants of feeling connected to or disconnected from the people around you?

Nick: Right. I think it actually really reflects, I think, something Ari was just saying about how we are maybe below our norm right now, in terms of how we’re connected to community and how we interact with others, that we for so long interacted in communities of 150, or were set up this way, and now globalization, how easy it is to move within countries, many factors that tech, while it’s not incentivized to support our wellbeing, but for other things, so you ended up with this really fractured social fabric. I think right there, you just have us operating like this, and suddenly, you have a situation where we’re forced to rely on our neighbors, where we can’t travel in the same way, where we aren’t constantly going to conferences. For better or worse, we’re forced to act out the symptoms of community.

Nick: In some ways, also, we’re stuck in our homes, so it’s really tough psychologically, but it also means that we’re going on walks together and we’re seeing the people around us. An open mic here, and play music, and we’ve met all of our neighbors this way. I mean, it’s a great example. I really feel that for sure, in some ways, feeling more connected. I think at the end of the day, a lot of it has to do with time. When you think about how much time during the day we spend on screens, how much time we spend in the places we live versus other places, how much time we spend commuting and really doesn’t leave much. Better or worse, that is the main limited resource, and now we’re spending it with the people around us. So, I definitely think that’s a silver lining, or it makes a difference.

Nick: And then suddenly, of course, we learn more about our neighbors and we start to feel that sense of connection and we have things that we bond around and we do activities. So, I think it’s a wonderful development, actually, or something that we all have picked up on as this has gone on.

Brooke: With COVID, certainly, there’s an opportunity for us to really be empowered. The epidemiological knowledge that we have about this virus suggests that our actions really do have a big effect. Maybe not each individual person. It really is action at the level of individual people that’s going to determine how well or badly this plays out. So, we do have a feeling of empowerment, and that feeling is probably backed up by the evidence. We don’t just feel empowered; we are empowered.

Brooke: And I think that those are two important things to keep in mind. One thing is to promote the sense of empowerment, and the other is to promote the reality that underlies that, that people actually do have real opportunities to be the change that they want to see in the world, to borrow a terribly tired phrase.

Brooke: So, how can we use behavioral science to promote both of those things? We can address them in turn. Maybe let’s start with the feeling of empowerment. Why is it that, in certain circumstances, when in fact we do have a lot of power, we don’t always necessarily feel it? And maybe because we don’t feel it, we don’t act on it.

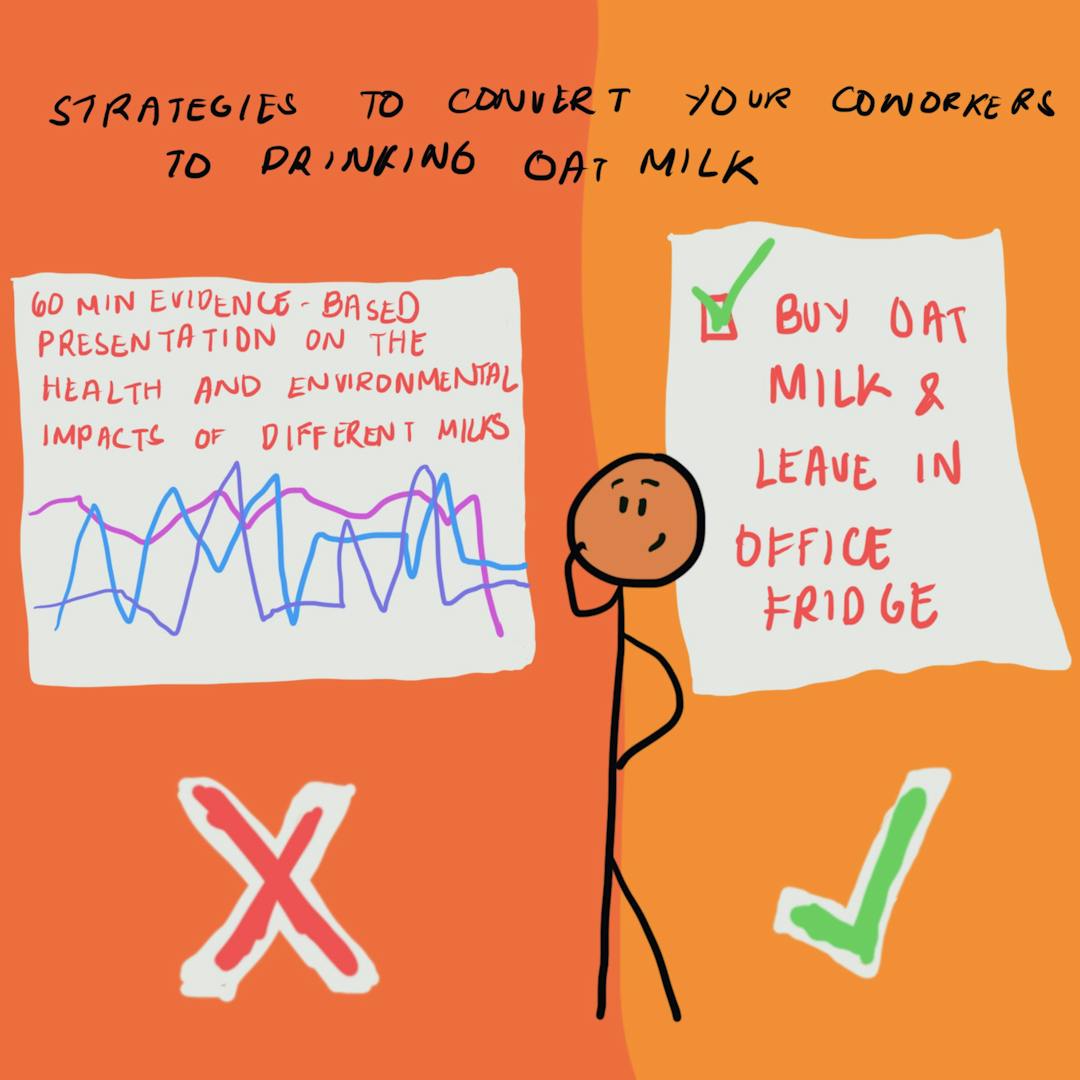

Ari: It’s hard sometimes to know what the right way to act is, right? There’s this idea of behavioral science of choice overload, that when you’re presented with too many options, you don’t feel thankful that you have 30 different choices. You actually just shut down and decide not to choose at all. There’s this great study where the folks go into a grocery store and they see six jams on a table and they are allowed to choose one, and they decide which one they buy. And then a different group in the other condition, they come in and they see 30 jams out on the table. And you’d think more jams, better, you just can pick a flavor that you like more. More people approach the table because there’s this idea, this paradox of choice that people think they want more choice. You come up to it, it looks exciting, there’s lots of them. And then you get overwhelmed by the choice difficulty. Then you’re like, “Oh my gosh, do I really want boysenberry, or do I really want blue raspberry jam?” And you basically ended up deciding that it’s too complicated and you take the easiest choice of all, which is no choice.

Ari: And so, I think the thing to take away from this study is that when we get overwhelmed by all of the options available to us, sometimes we just choose not to act. And so, to your point, of course there are a lot of ways that we can help, right? There are a lot of things that you can do. We actually are incredibly powerful right now, right? I mean, there’s a thousand different causes that you could donate your money to, there’s a thousand different ways that you could support and fight back. And that actually makes it harder, because if there’s only one or two things we could do, if we were just dealing with climate change, then it would be, “All right, let’s all just make sure everyone does this one thing.” But suddenly, when you’re dealing with, “How do we fight back against police brutality? And also, how do we deal with the fact that Trump is trying to destroy democracy, and how do we deal with the fact that the environment is on fire and there’s 40 different ways to do each of these things?” I think you can then feel a little bit lost.

Ari: We see this a lot, is people asking “Where can my money do good? Where can I actually help?” One of the things that we’ve spent a lot of time thinking about at Momentum was actually helping people understand which organizations are doing great work. We spend a lot of time working with and talking to charity evaluators and reading reports and trying to understand, “Okay, if you really care about clean water, where are some of the best charities in the world giving to clean water? If you really care about women’s empowerment, should I donate to BCRF or should I donate to Planned Parenthood? How do I figure that out?”

Ari: And so, we’re trying to help people actually sort through some of that, because there are so many different options. And I think that applies not just to giving, but to all of the ways you can engage, whether it’s volunteering, whether it’s posting on social media about it, or whether it’s calling people to get out the vote. There’s so many different options, and I wonder whether maybe a sense of powerlessness comes from the lack of clarity around what you should do. “What is my responsibility? What is enough? What is going to work?”

Nick: I think that’s super interesting. I think building on that, to your question, how can behavioral science then help people be powerful? And I think there are two really interesting building blocks that come right from what Ari was saying. One is that I think it can help people even sit back and evaluate what are the things that help us be powerful so we can sit and think, “Well, is it calling our senators?” Let’s take the example of political participation in the upcoming election, right? You can donate to these places, and as Ari was getting at, which places are effective? And it can help us think about how to evaluate these places and run RCTs or think, “Okay, well, what kinds of political behaviors should we be taking?” And it can help evaluate those.

Nick: And then, I think even more importantly, in helping us do them, right? And so, there’s this question about how we make it easy for people to exercise their power. On one end, they’re stealing power, and of course, we don’t want people to license, or we don’t want people to feel that they have power, or recycle and then not support longer-term structural policies around climate change. And so, you think, “Okay, well, how do we then make environments that make it much easier for people to do things that support that power?”

Nick: So, there’s a lot of work on how you get people to the polls. And in fact, we don’t do a great job. 55% of us turn out compared to other countries, right? And so, you can think, “Well, one thing would be making the environment easier, it might be that you don’t have to go to work.” So, changing the environment that way, where it’s a holiday, might make it a lot easier for people, right? I know a lot of the evidence has shown that relational voting is a really effective tactic. So, it means basically, how do you get your friends to get their friends to get people to vote and create this wave? And there’s a lot of work around, do you text people? There’s a bunch of interesting behavioral science work on vaccine uptake and how effective it is to text people or having people show up to school. So, I think there’s just a ton to learn and pull from, and Todd Rogers and his group at Analyst Institute, and there’s a whole lot of people doing this work, applying behavioral science to just that piece about how we exercise our political power.

Brooke: Yeah. So, it sounds like there are three components that I can pull out of what the two of you have just said. One is about ambiguity and understanding what the options are. The second is about choice overload and trying to streamline options of saying, “Okay, well, if X, Y, or Z is the outcome that you’re looking for, here’s a prioritized list in terms of how impactful these various types of actions are in the ecosystem that you’re working in. Here are charities on how effective they are and moving the needle on these key things we care about. If you really want clean water, how far does your dollar go with one charity versus another in helping to provide clean water to people?” And so, if we’ve got ambiguity reduction and managing choice overload, the third one then would be something about transparency on outcomes. And maybe not just transparency, but salient of outcomes. Helping people to feel the impact of their actions as well, because that’s something that I picked up in which you were talking about, or am I just hearing what I want to hear?

Nick: I think that’s exactly right. I’ll just say that people want to know what happens with their money. If people aren’t sure where to give or how much or when, but certainly, one of these big barriers is, “What did money achieve? When I normally buy something, I get something, and I have a sense of the value there.” And so, often, when we give, it just goes into this black box. A lot of what Ari was touching on, a lot of work we’ve tried to do here is really translate what’s happening, where money goes, it goes to nonprofits, they give directly.

Nick: Or Against Malaria Foundation, they’re working on distributing bed nets, it turns into this many bed nets. This many bed nets work for this amount of time, and it protects somebody for this many years. We don’t necessarily want to end up talking about quality-adjusted life here, so a lot of evaluation of impact happens in that way. And, then of course, what we deal with is now the science of translating that into something that’s interesting. It’s certainly a piece of a puzzle, I think.

Brooke: And how do we bring identity back into that? Maybe that’s what you’re hinting at there, is how do we take those impacts and translate them into pieces of information that will be meaningful to people, that these become elements or building blocks that they use in constructing narratives about who they are, about building their identities that find the person that helps to do this thing?

Brooke: As a charitable donor myself, I’ve seen already for years and years, the letter arrives in the mail of, “Here’s little Samantha who got such and such a thing because of donors like you.” I don’t know. Maybe the tactic just feels tired. Yes, of course, I want to feel that I’m helping individual people’s lives, but somehow, the narrative of just one person’s life doesn’t feel like it’s landing. I don’t feel like I really can take ownership or take pride or some feeling like that, and like, “Oh, okay. My contribution, my effort went directly to helping this individual person.” Because I suspect that if the neighbor donates to the same charity, the letter in the neighbor’s mailbox was probably also about Samantha.

Ari: I mean, this is a really good question. I mean, the question of how do you help donors feel connected to their giving, right? How do you help people feel like what they’re doing is actually making a difference, is a really fundamental question to helping people want to give. As Nick said, you don’t want anybody to be going to the drop box and you don’t want to feel like you’re just giving it to some ambiguous organization, that bureaucratic thing that you never hear back from.

Ari: The standard models of how to fundraise worked really well for a long time, and charities have this playbook of like, “Here’s how we’re going to raise. All right, you’re going to call people on the phone, you’re going to build these long term relationships, then they’re going to write you a check in the mail, and then you mail them a letter that says, ‘Congratulations, you helped Samantha.’” That worked for quite some time, I think, on a certain generation of folks.

Ari: But I think as Baby Boomers stop being the only financial horse in the donation ecosystem, as millennials and younger generations start actually getting jobs and supporting charities, they’re looking for a little bit of a different relationship. They’re not looking for a letter in the mail; they’re looking to feel like it’s actually something that they can connect to and relate to. And the biggest issue we’ve seen here is that the easiest option when it comes to donating by far is recurring giving. Recurring donors give on average… A first-time donor normally has a 23% return rate in terms of whether they actually come back and give again. Recurring donors have an 87% retention rate. They have an 800% higher lifetime value, so they give eight times more over the course of their relationship with the charity.

Ari: But that connection as a recurring donor feels so transactional, right? You sign up for this monthly donation, and maybe you get a letter if you’re lucky. A lot of them might just send you a tax receipt in an email, and then you’re done, and then you just get this drain in your bank account month to month. This feels like a utility bill. And I think trying to figure out how to help donors actually connect with the charity, feel like they’re a part of that narrative, is one of the big things we’ve struggled with Momentum. It’s been one of the big inspirations for what we’re doing. What we really want to do is help people have that frictionless option of recurring donations, have it set up so they don’t have to keep deciding over and over again to make that decision to support, but still feel that tie, still feel that connection to what the charity is doing, and to their own life, right?

Ari: That’s why we tie these donations to the things you’re doing, right? Because now, when I get that cup of coffee at Starbucks, now I know that it’s helping someone else get clean water. And so, I can now directly feel that connection in a different way than if just once a month, there was a ding on my account. And so, our hope is that we can actually bring back that sense of identity and that sense of connection into the giving process, by making it less of a one-way relationship, less just, “I send money to you,” but more of a closed loop back and forth.

Brooke: There was also an interesting feature there, which is the thematic connection between which types of activities you are undertaking and what type of cause you’re supporting. So, you mentioned, “When I buy coffee, I’m supporting someone else getting clean water.” There’s a strong bond between those two things. “I’m going to sit down and drink this thing, and as I do it, I’m helping someone else to also drink something that’s critical for their life.” Whereas if you said, “Okay, well, I’m going to tie something thematically completely unrelated, like every time I take a thousand steps, I’m going to contribute enough for one more cinder block for a hospital, random association.” You might not have as close a bond to what it is that you’re giving because that association isn’t there.

Nick: It’s a really interesting question, and one that I know we ourselves are pretty excited to learn more about. So, with the water example, I think there’s really something there in that resonance. And in particular, I think it shows up when these actions, and there’s many different use cases are setups here, but when these actions around offsetting your own behavior. Certainly true to that when I take a Lyft or I get gas, and it makes some sense that it would go to climate, right? And there’s this whole question of actually accounting for the externalities. And I think it’s just pretty salient when we are doing things that cause harm that we might want to offset those, or even go beyond that. At least, I’m super interested in learning more about how this holds up for things out in the world and then in general, how important that thematic connection is.

Nick: I want to say one thing about what you said earlier, just the last question, I think the question on impact is so interesting, and your example is a really interesting one actually, in that it feels to me like this almost uncanny valley, or a very nuanced take on behavioral science, and that what you got in the mail is pretty nice, right? You’re getting something on Samantha, and there’s the famous Stalin quote that, “One death is a tragedy, a million a statistic.” And there’s this work in behavioral science, in particular on giving.

Ari: Sorry, sorry. I just want to say I really love that quote, because a really nuanced understanding of how donation psychology works, but it’s coming from Stalin, so you have to figure he’s using this as an excuse for why it’s okay to murder millions.

Nick: That’s right. Yeah. The other I would say is always raised is the Mother Teresa one. “I look at the masses, I’ll never act, but if I look at the one, I will.” And there’s some good examples of this out in the world of people really doing this, and I think my favorites give directly, who really try to do a good job of showing you this.

Nick: And what you’re getting at that’s really nice is this almost uncanny valley, the identifiable victim effect. It’s really good, but if you think they’re just playing with you, and Kiva was in the news for this, of it being representations of people, then people feel uncomfortable, right? People really want this authenticity. And so, your concern, I think if you went to your neighbor and they had somebody else, you might be like, “Oh wow, I feel super connected there.”

Nick: And GiveDirectly did something here with a COVID relief where they did Project 100, working on raising $100 million and unconditional cash transfers to people in the States. And if they wanted, they could film themselves with their iPhone and just answer some questions about what it was helping. And of course, they’re quite moving. I think there’s some concern here of what’s often called poverty porn, or I think we feel uncomfortable with that, this idea of just sending you Samantha. And in particular, if it’s Samantha going to 10,000 households, but if really each person’s getting somebody and you’re feeling connected and you’re even having a conversation, that is going to make you feel more connected.

Ari: I don’t know. To push back just a little bit, just to totally steal words from Michael Faye’s mouth, GiveDirectly, we were having a conversation about this exact question. We were chatting a few weeks ago about how GiveDirectly thinks about… This is called the identifiable victim effect, where you identify someone you’re helping, then that person gets more money, typically. And what Michael Faye was saying was that actually what they find is when you let people do this, especially if you make it this actual connection one-to-one, or if you go so far as Kiva does where you can pick who you’re supporting one by one and say, “I want to give my money to this person or that person,” like Watsi does, what you find is that people then support lighter-skin folks, more attractive folks, younger folks, so just trade it off between different things like this.

Ari: And when it comes to how to get people to give, sometimes you have to think about do you want to go about things in what we might think of as more of a right way and maybe a more fair way, or do we care about maximizing the number of dollars? How much do we care about pimping out the images of people in poverty, that allows the charity to raise more money? In the end, does that justify that process along the way? How do they go about it? It’s all of these complicated questions of when you start getting into the weeds of donation psychology that are quite nuanced.

Brooke: Just on a related note, while we’re on this topic, I wanted to bring up one idea that has been, for me, very influential in terms of charitable giving, which is direct cash transfers are a really powerful thing. The time that you shouldn’t give a direct cash transfer is when you feel that there won’t be access to some critical thing in the area, where the money is actually going to end up, or in circumstances where something purchased in bulk could be dramatically less expensive, or any specific reason that you have that we, acting collectively, can achieve more than an individual person with the cash in their pocket.

Brooke: Other than that, it’s just pure paternalism. It’s just you expressing your will of how you feel about someone else that you think you can make a better determination of what will help someone else than they can make for their own circumstance. And to me, that’s very strongly tied as well to this idea of the page on Samantha that we put together, it’s like we really productized Samantha. We make her this object, rather than allowing her to be a person with agency who tells her own story. It’s like, “No. You are a thing for us to write this exposé on in order to extract more cash from people who are looking for some social license.

Ari: The standard story people talk about is baby Jessica, not Samantha, but the actual story is that there’s this baby who got trapped in a well. Before GoFundMe, but something like the equivalent of a GoFundMe for baby Jessica, and they raised millions and millions of dollars to get baby Jessica out of the well, which was far more money than they needed. And so, I think one of the other dark sides of this is that in addition to the question of, is it okay to exploit these stories and productize them, as you’re talking about? I’m saying that like it’s clearly a bad thing, but I think it’s a nuanced, complicated question, because I think a lot of these people would say, “Please use my image if it’s going to allow me to get more money and it’s allowing me to get the resources I need.” I think it’s a complicated question.

Ari: In this case, sometimes it also means that the resources get directed to the person who has the best story, directed to the person who has… Maybe it’s the prettiest picture like we’re talking about, or maybe it’s just they had a better author write their GoFundMe. And that this person gets $50 million and this person gets $3, or that we will trade all these psychological biases because we evolved to want to help people, not just who look like us, but people who are within our community, people who are close to us physically, people who we see because it’s visceral.

Ari: Because again, when we were evolving, we saw the same 150 people around us all the time, and the evolutionary rewards with helping people in your community, because then they’ll help you back. And sending your dollar overseas was not going to have a lot of… It wasn’t even possible, let alone certainly wouldn’t have the social benefits that would be more likely to pass on your genes to your children. Right? And so, we end up with all of these biases that also predispose us towards helping a certain subset of people who are close to us, who look like us, who are familiar, and we’re comfortable with, who have a better story, who happen to catch our attention, who we are emotionally connected to. And sometimes that’s a good thing, but sometimes it isn’t. There’s a lot of reasons. But actually, a lot of times, your dollar goes further overseas, where it’s cheaper to get some of the same interventions that can help more people. We’re not wired that way. That’s not how we feel, or how we’re predisposed to give.

Brooke: That raises another interesting issue, that behavioral science as a descriptive and potentially explanatory science. I don’t want to dive too much into the philosophy of science in this, so let’s just stay on the surface of that one. But if what behavioral science is doing is mapping out these cognitive biases and heuristics, and helping us to understand what kinds of decisions people actually do make and what kind of behaviors they do undertake by contrast, to a rational, economical model where you’ve got this rational agent.

Brooke: Behavioral science is helping us to map out these contours of how people decide and how they act. And in some instances, we say, “Okay, well, we’re going to double down on those. We want to increase the salience of this in order to do such and such a thing.” And in other instances, we say, “No, this is a problematic, biased hold. We think that it’s wrong that people donate disproportionately to people who look like them or tell good stories or something like that.” But where does this critical power come from? Where do we put our feet down on solid ground to push back and make these kinds of value judgments about what kinds of decisions people ought to make, and what kinds of behaviors people ought to make? Which is a departure from mapping out how they do decide.

Nick: That’s right. And I think it’s not necessarily within behavioral science’s domain. I think, often, behavioral science ends up being a tool. And even in the field, I think you see this conflict, where it’s one thing to say system one and system two, but it’s another to call them biases. And so, you have this rise of that because, of course, we think about the rational economic man, because we have this, and where does that come from? What we came up with, and it was deciding that this is more reasonable than not, and there’s all this work on scarcity. Or you take something like the marshmallow effect, where it’s about self control. Well, if you don’t have a lot of resources and haven’t your whole life, or maybe you don’t expect that you’ll get another marshmallow, it maybe has more to do with other things than just this really tight story we tell.

Nick: And so, I think on the other side, there’s work developing on this argument that maybe these aren’t biases. And I like how you use the word heuristics. To Ari’s point about our evolution that they come from somewhere of course, and that they help us do things often, but how they’re applied matters, right? I think that these quick intuitions can be really helpful and they can be very harmful, and they’ve done a fine job of measuring them. But more and more, we’re looking into when this gets applied to things in society, right? How do they have harmful consequences?

Nick: And I don’t think it’s really within the science of psychology that there’s some right or wrong thing here. It’s often how they’re applied, and it’s often that we consider them and say, “Well, it has nothing to do with behavioral science; it has to do with our judgments about fairness,” that it just seems strange in some ways that we would say we should ignore a billion people that don’t have clean drinking water. You could sit here and say, “Okay.” It’s a very different conversation about who we should support and why, and I think behavioral science shows us that we’re unlikely to support people overseas.

Nick: The next question is: well, is that right or wrong? We could sit here and just say, “Well, if we value everybody, if humans are humans, if there’s no strong moral reason to say, ‘Well, we have to help only people who look like us,’” then from there, behavioral science ends up mapping or illuminating ways in which we don’t align with our values. And I think, though, you have to start with your values and how you want to make a difference.

Nick: And for us, some of us spun out of it, right? I mean, even that example, it is true. A billion people aren’t sure whether they’ll get clean drinking water or not today, and I’m not making coffee here. And so, I do think part of it, at least for us, came out of this. If you make more than $30,000 a month, you’re in the top 1%. We, in general, have value around helping people, and many people in general don’t want their money to go to waste, or they really want to do this. Applied in that mission, behavioral science can be helpful in saying, “Okay, well, I want to know that I’m helping.”

Nick: Or even if this happens with voting, in this case, where we’re like, “Well, I want to know that my money is going to turn out the most votes.” And so, it’s really helpful to know that relational voting is one of the best get-out-the-vote tactics, and a lot of work in behavioral science has shown us that. But the value of me wanting my money to turn out the most votes, that comes from me.

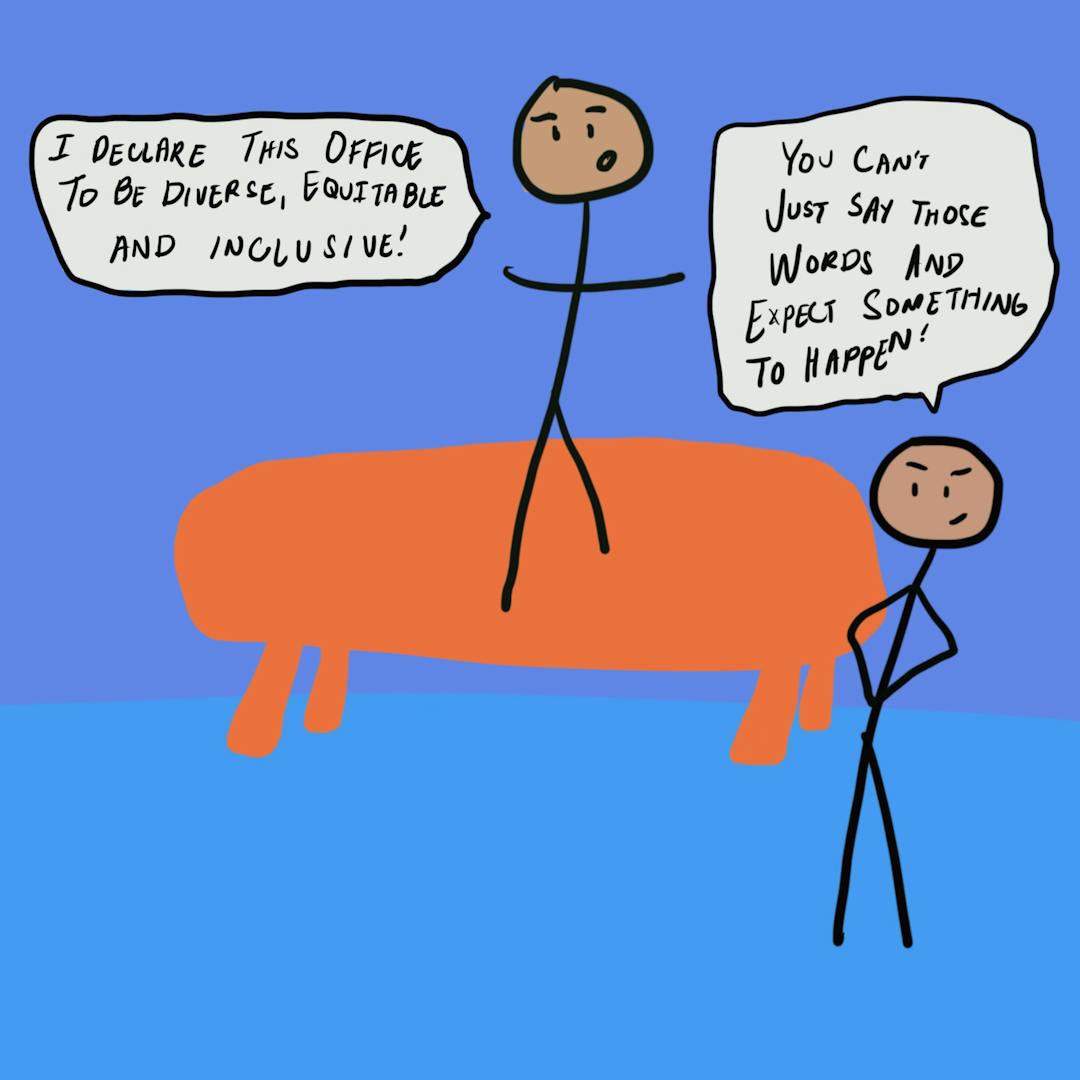

Brooke: In terms of conducting ethical behavioral science, and especially when we get into the world of applied behavioral science and putting interventions out there into the wild, how do we do that responsibly? So, you mentioned that this lies outside of the province of behavioral science, but we still, in organizational settings, we still really rely on the behavioral science experts to also be the experts of how to deploy their craft in an ethical way. So, how do we square that circle? How do we create circumstances for really ethical behavioral science to be practiced, when currently, we rely on people who don’t have much training in ethics to lead that effort?

Ari: It’s a really complicated question, where I think one of the common critiques of behavioral science is that it’s too paternalistic, right? It’s making choices for us that influence the behaviors, the choices we’re going to make. And there are a few different responses to this, right? So, one is that, to some extent, you’re never free of the influence of your environment, right? To some extent, your environment is influencing you, and we can choose whether that’s influencing you in a random way, or whether someone’s at least trying to influence you in a positive way.

Ari: Much of how our environment is designed is, in fact, sometimes influenced in a negative way, right? If you go into the grocery store, I promise you, their goal is not to help you make the best decisions; their goal is to get you to buy one more Kit Kat bar, right? So, they place the Kit Kat bar on eye level for the four-year-old child, who will then ask, “Mommy, can you please buy me this Kit Kat bar?” So, we can certainly use behavioral science in bad ways, because we can set up the environment in ways to try to get you to spend more money. Or it can be truly random, just wherever the grocery store happens to be set up, and then you just buy certain things. Or we can try to set up groups and organizations that are striving to help you.

Ari: So, at the very least, we’re trying to help you make decisions that you yourself would want to make. There’s this idea of reflective endorsement. What would you do in the moment decided by your environment, versus would you later on say, “I’m glad that I made that choice?” Later on, maybe you aren’t glad that you… The cake, and the moment that you see the cake, but maybe you’d be glad that if your environment was set up so you didn’t have a cake in front of you, and then you’re not going to actually eat the cake, right?

Ari: So, I think striving to use behavioral science to empower people to achieve the things they already want to achieve is one answer to this. The other is trying to use it for things that are good for the world, right? Hopefully, these are usually not at odds, although they obviously run into questions like, “Well, what if people want to do something that’s bad for the world? Then, is your obligation as behavioral scientists to set up the environment to meet their own needs, or is it to just improve the world?” But I think usually, these things are aligned. So, I think it’s usually more that life gets in the way. The world we happen to live in is filled with temptations, it’s filled with all sorts of different things. It’s filled with advertisers, it’s filled with Facebook that has spent billions and billions of dollars trying to make it as addicting as possible.

Ari: And so, the environment we’re in most of the time is, by default, either neutral or intentionally designed against your wishes, to get you to do things that you otherwise wouldn’t. And so, I think, sure, we may not all be ethicists and we may not all have the perfect answers, but I think that if you start with a baseline of trying to do the things that we think are better for the world and better for your own goals, that’s already a huge jump on where it otherwise would be.

Nick: And to your point, work with your question, I don’t know really that we should be relying on behavioral scientists to bring in a moral framework. And really, what Ari touched on, we’re trying to align it with how people would like to live. And often, I think about behavioral science as a tool or a technology, and it’s often deployed, as Ari touched on, in the world of advertising, or it’s often deployed to get people to buy things, or to make things feel as if they want something. And thinking about nuclear technology or all of these, it really depends on how it’s deployed. And I think, for the most part, behavioral science, the way you see it, there’s a lot more money behind it being deployed to get people to buy things and to get people to live how they want to live and to help them.

Ari: But there are moral judgments being made in a lot of these scenarios, like the standard example of organ donation, where in some countries, when you go to get your driver’s license, the default is that you are not signed up to be an organ donor, and you can check a box and become an organ donor. And then, most people ignore it, they don’t check the box. They just go with the default, and you get 7%, 8% of people. In other countries, the flip is true. You’re, by default, an organ donor when you go to get your license, and you can check a box to say, “Don’t want to be an organ donor.” People still ignore the check box, don’t pay attention, and then, by default, they become an organ donor, and you get 80%, 90%.

Ari: Someone made a moral decision here that what you should be doing is donating your organs. And I’m not even sure if you ask people to reflect on it. To just push back on what I was saying a few minutes ago, I don’t know if people would even have a view reflecting about what they truly want. I’m not sure there is some deep, true desire there, the way rational economics would want. Sometime there is, sometimes you’re like, “Yeah, I really just want to make this choice.” But other times, there is no reflective thing that you really wanted. And so, then someone making a moral judgment about what they think should happen for the world. And yeah, I think it’s a hard question. Who gets to decide whether or not people want to be organ donors? I don’t know.

Nick: That’s the question of how you build a good political system, right? We decide, the behavioral scientists decide, up in the crowds, who we elect decide.

Ari: I think the presidents and CEOs of the companies building AI cars get to decide whether or not it kills the passengers or it kills the people on the road.

Nick: There appears to be a little bit of some regulatory capture there, right? Who decides? I think what Ari’s getting at there is so interesting.

Ari: Trying to find people who are incentive-aligned with you. Maybe that’s elected officials or politicians. Maybe that’s trusted researchers or something. But a certain amount of topics you get in corporations, they’re probably not incentive-aligned.

Brooke: So, that seems to actually tie up very nicely with the point that we started on. Nick, you asked me what my perspective was on empowerment and people not feeling empowered, and then I said that my sense is that so much of the stuff that we care about is boxed out of our lives by the fact that core business, if you will, is just not aligned with what we’re looking for. Perhaps what we’re seeing here is more of the same when it comes to ethics and behavioral science, but the kinds of outcomes that behavioral scientists tend to be directed towards most often are not necessarily outcomes that are in the best interests of the people who will be subject to those interventions. And that if we don’t rethink how the core business is stoked out, we probably shouldn’t expect to really move the chains that much.

Brooke: Giving a two-hour ethics seminar to every behavioral scientist before they start in the field seems like this cartoonishly set-up-to-fail intervention, that for sure, you’re not going to see massive systemic change from just telling someone for two hours, “By the way, you should counter all of these enormous pressures that dominate everything in your life.”

Nick: You don’t see that, actually. And in fact, the people teaching those seminars aren’t more ethical as it is, even ethics professors not being necessarily more ethical.

Brooke: And even a checklist or a process, something that helps to increase the salience in a specific application domain, and maybe that’s not really going to cut it either. We might just have to rethink what it is that we’re trying to achieve if we’re going to make significant progress on the ethical application of behavioral science. And I love that you brought up AI in this as well, because I feel that that field is also grappling with this issue of, “How do we do responsible AI?” But what doesn’t seem to get challenged-

Nick: Giving them a checklist isn’t going to help. To give it to every AI engineer, and let’s have them open AI, just sit with a checklist next to them as they develop it and be like, “Oh yeah, that’s right. I really need to think about society, even though Microsoft just put $1 billion into the company.”

Ari: The light bulb joke about psychiatrists: How many psychiatrists does it take to change a light bulb? Only one, but the light bulb has to really want to change. You can give as many checklists as you want to AI researchers. That’s not going to do the trick. Your ethics course isn’t going to do the trick. You have to set out what behavioral trends, the toolkit, as Nick said. And you can use the really powerful tools that you can use to influence behavior, and you have a moral responsibility as a behavioral scientist to use that for good. But you have to want to try to use that for good, and I don’t think we can force people to do that.

Ari: I think it’s really about setting out with that as a goal. That’s one of the things that brought us to Momentum was Nick and I sat down and said, “Wow, this is an incredible toolkit, but it can be used on so many things. How could we actually use this in a way that would help people actually do more good in the world? How can we use this as a force for good?” You’re not setting out with that goal in the first place, and it’s something really hard to try and trick you into accidentally using behavioral science for good.

Brooke: All right. So, I will hop on your platform in the next couple of days and look for a charity that is most effective in shuttling my dollars towards reforming the underlying logic of society.

Ari: There we go. Systemic change.

Brooke: Anyway, guys, thank you very much for this conversation. It’s been great. Very illuminating, very interesting. And I hope that our listeners have taken a few practical nuggets out of there as well. One for me is, you have to think about what that overriding logic of incentives looks like and how strong the intervention needs to be if you want to see people exhibiting behaviors that might detract from that fundamental logic. Any summative insights you wanted to pull out before we sign off for today?

Nick: I really enjoyed chatting with you today. And yeah, one of the more interesting conversations. I didn’t think we’d touch on so many things that are so important to me. It’s a rare thing, especially these days, when so much of our time is operating. It was very nice to chat with you.

Ari: Yeah, it’s a pleasure.

Brooke: Well, thanks guys. I hope that you’ll come back soon.

Brooke: If you’d like to learn more about applied behavioral insights, you can find plenty of materials on our website, thedecisionlab.com. There, you’ll also be able to find our newsletter, which features the latest greatest developments in the field, including these podcasts, as well as great public content about biases, interventions, and our project work.

We want to hear from you! If you are enjoying these podcasts, please let us know. Email our editor with your comments, suggestions, recommendations, and thoughts about the discussion.