Ethics for Aesthetics with Jonathan Haidt and Alison Taylor

If you think about the way that business ethics is conceived and operationalized within organizations, I would in general argue that what is called ‘business ethics’ has very little to do with business ethics. It is rather a set of related but separate functions that are designed to protect the corporate entity from reputational or regulatory risk. So the role of these functions is to provide a shield that protects the organization from these outside forces.

Intro

In this episode of the Decision Corner, Brooke speaks with Jonathan Haidt, the Thomas Cooley Professor of Ethical Leadership at the Stern School of Business NYU, and Alison Taylor, the executive director at Ethical Systems and also an adjunct professor at NYU. In today’s episode, they discuss the role of ethics and values in business, including the challenges associated with Generation Z, and the workplace culture changes that have been fuelled by the evolution of social media and increasing polarization in countries like the United States. They talk about the challenge of hearing from all members of the workforce, and not just the most polarized who are shouting the loudest. If you’re curious about whether businesses should remain politically neutral, have an interest in business ethics and the changing landscape of modern corporate leadership, this episode is for you!

Some of the topics discussed include:

- The challenges that come with leading a multi-generational and politically motivated workforce.

- Should businesses take a stance on social issues? Is neutrality a viable position?

- Business ethics as a way of conducting business, as opposed to being a safeguard against legal action or public outcry.

- Fostering a safe culture where employees feel comfortable expressing their opinions without fear of backlash from the public, or their co-workers.

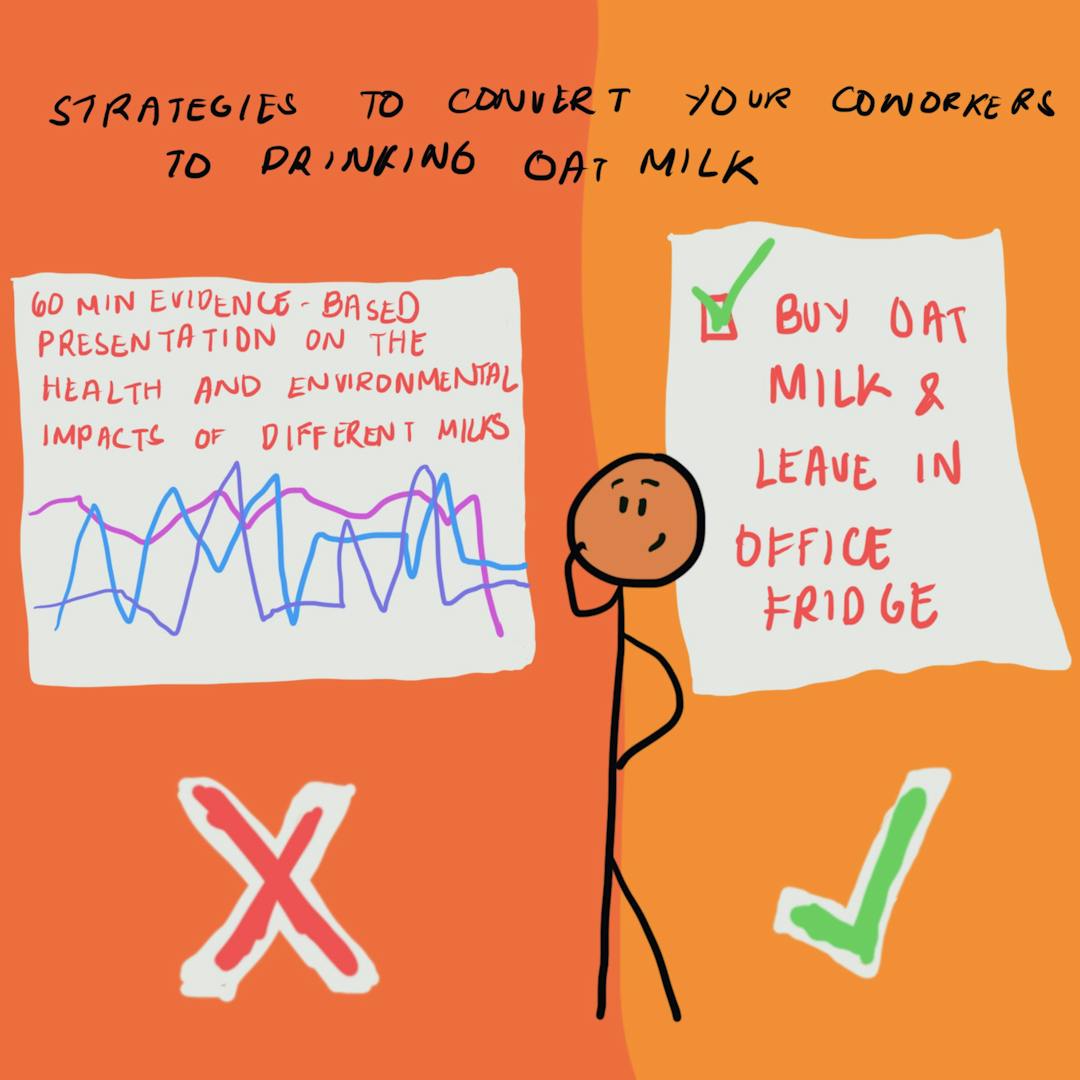

- The role of behavioral science in business – beyond the marketing department.

The conversation continues

TDL is a socially conscious consulting firm. Our mission is to translate insights from behavioral research into practical, scalable solutions—ones that create better outcomes for everyone.

Sneak Peek

Today’s Big Leadership Challenges

“Gen Z, the people born in 1996 and later, they have really high rates of depression and anxiety. This isn’t just that “Oh, they’ve got different values”. They have some very good values, but they’ve been over-protected. They’re fragile. They have a lot of problems, and it’s been very difficult for companies to integrate them. They have very different demands from any previous generation…Part of the reason that Gen Z is in such trouble is the second trend, which is that social media changed fundamentally between 2009 and 2012. It became much more engaging. It became algorithmized based on engagement data, and it became much better at spreading outrage. It really became an outrage platform.”

An Argument for Political Neutrality in Business

“As soon as it becomes normal for businesses to take a position on the issues of the day, then it becomes obligatory for almost all businesses to take positions on almost everything, because some employees are going to push them that way. If the employees in an industry all lean left or all lean right, well then we know exactly what position they’re going to take on every issue.”

Why Political Neutrality in Business Might Not Be Viable

“Uber made a shareholder value-based, neutral decision to keep operating its service during the strike. I don’t believe that Uber saw itself as taking a position one way or the other in making this decision. That decision was not read in neutral terms…so the situation in the US today is such that the middle ground, the neutral middle ground has become a very dangerous place to be.”

The Weighted Input of Employees

“I don’t mean the average employee, I mean the ones who are loudest, who tend not to be from both sides, they tend to be from one side, depending on the industry. So I think that would be just terrible for everyone, including the businesses and including the employees, because the employee activists don’t usually speak for most employees.”

The Role Of Behavioural Science in Business

“We really think about behavioral science as a way to learn about what the needs are of the clientele, only to squirrel away behind the scenes and say, “Okay, what is the most valuable value proposition that we can articulate for those people?” “What is the most valuable thing that we can do for them?” Not just “What is the most valuable way that we can articulate what we’ve already decided we’re going to.”

Collectivism and Group Dynamics

“We’re very individualistic societies. Obviously in the US and Canada, we don’t like this idea of how influenced we are by people around us. I think this has really stymied research, but everything that’s happened in the last few years, whether it’s more awareness of systemic racism, or COVID, or climate change, has really, I think, re-focused people on how important group-level dynamics are.”

Creating the Environment for Change

“I think this is a huge problem, and it speaks, again, to this very reactive, reputational-driven kind of norms that we have. I think you see it both internally with companies panicking if they get critiqued. You also see it externally with a very shallow reaction to getting criticized on whatever the issue is of the day. So all of this is solved by long-term thinking. That’s an easy thing to say. It’s a very, very difficult thing to do. But psychological safety is a good principle, I think, to proceed on.”

Transcript

Brooke: Hello everybody, and welcome to the podcast of The Decision Lab, a socially-conscious applied research firm that uses behavioral science to improve outcomes for all of society. My name is Brooke Struck, research director at TDL, and I’ll be your host for the discussion.

My guests today are Jonathan Haidt and Alison Taylor. Jon is the Thomas Cooley professor of ethical leadership at the Stern School of Business NYU. Alison is the executive director at Ethical Systems and also an adjunct professor at NYU. In today’s episode, we’ll be talking about ethics in action in the corporate world. Jon and Alison, thanks for joining us.

Jonathan: Our pleasure.

Brooke: So please, before we dive too deep into the meat of this, tell us a little bit about yourselves and what you’re working on.

Jonathan: Yeah, I’ll start. So I’m a social psychologist. I spent most of my career at the University of Virginia. I came to NYU in 2011 sort of on a whim, but they liked me, I liked them. So I came here. Since I study moral psychology, I thought what was needed was a project that would really bring the insights of behavioral science to business people, because it was clear that business people don’t read the psychology journals, and business ethics research was mostly the incentives are published essays for other academics. So there really wasn’t a good connection. There were few good people looking at behavioral ethics. So I created an organization, it was very informal at first, it was just a website and a bunch of people I knew. I bought the domain name EthicalSystems.org. So that’s one of the main areas that I’ve been working on here at Stern. There are many social psychologists in business schools these days, and I think one of the best things we can do is bring social psychology in particular, and social science in general, into the study of business ethics. So I started it in it was about 2011, 2012 sort of, but then really for real and we became a 501(c)(3) in 2014.

Alison has been the executive director of it for about a year and a half now, and so yeah, she’s… Well, Alison, what do you do? Who are you? (laughter)

Alison: I’m the executive director of Ethical Systems. Jon’s explained the purpose of the organization very well already. So I would just say I came to the same conclusions as Jon about what is needed in business ethics, but via a very different route. In my 20s, I worked on questions of political risk and why companies invest in some countries rather than others. I then spent 12 years investigating corruption, first in the Middle East and Africa, then in the Americas. So very interested there, again, in how large multinationals behave in what used to be called high-risk frontier markets. I think we’re now all high-risk frontier markets.

I then more recently worked in corporate sustainability or ESG or CSR, depending what term you prefer, and I have a background as well in organizational psychology and culture. So having thought about questions of business ethics from an academic perspective, from a psychological perspective, and then in terms of ethics and compliance, and the more voluntary initiatives covered by CISR, I see that there is a very incoherent conversation that would benefit greatly from getting the best ideas from academia into the corporate world. So that is our ambitious goal.

Challenges of Leadership

Brooke: That’s a really great overview, and I think it transitions very nicely into the discussion that we want to have today. So what are some of the challenges that are facing business these days, especially around ethics and values and the way that ethics and values are put into practice?

Jonathan: I like to think in metaphors and analogies. I like to think of doing a really, really difficult thing, and then all of a sudden you discover that you’re trying to do it on a ship which is both on fire and sinking at the same time. There used to be game shows like this called Beat the Clock back when I was a kid.

So leadership has always been hard. It’s always been hard to get a group of people to work together on something and avoid all the politics and backstabbing and suspicions. So leadership has always been hard, but I’ve been studying how everything seems to be going haywire since around 2014-2015. First on university campuses, and I wrote a book with my friend Greg Lukianoff called ‘The Coddling of the American Mind’.

Then a lot of the same problems that we talked about there that were in universities, really flooded out into the corporate world around 2018, plus or minus. So this is the first major mega trend that all businesses have to deal with, which is that there’s a change of generations, and every generation makes fun of the one or two behind it, and they think that they don’t have the virtues that we had. That’s been going on since the fourth century BC. We have cool quotes. Even, I think, Hesiod before then, about what’s wrong with the younger generation today?

But this is different. Gen Z, the people born in 1996 and later, they have really high rates of depression and anxiety. This isn’t just that, oh, they’ve got different values. They have some very good values, but they’ve been over-protected. They’re fragile. They have a lot of problems, and it’s been very difficult for companies to integrate them. They have very different demands from any previous generation. So that’s trend number one is the generational trend.

Part of the reason that Gen Z is in such trouble is the second trend, which is that social media changed fundamentally between 2009 and 2012. It became much more engaging. It became algorithmicized based on engagement data, and it became much better at spreading outrage. It really became an outrage platform. It wasn’t that in 2004 to 2008 in its early days.

So social media has made it much more difficult to lead anything, because social media is so good at tearing things down, getting people together to be angry. It’s terrible at bringing people together. There are cases where it brings people together for charity, things like that. So it has some constructive uses, but overall, it’s a much better tool for destroying than for building.

Then the third, which is also related to the social media trend, is the massive rise in cross-partisan polarization, not so much on issues, but in terms of how much we hate each other. When people hate the other side, then a really bad thing happens, which is the ends justify the means. This, I think, has really affected the corporate world, because maybe we’ll talk about purpose later, but when you’re in a state of total war or what the researchers call high conflict, you’re focused on beating the other side. If you see that the other side is racist or fascist, if you’re on the left, or if you see the other side as woke, crazy, communists or whatever it is that they say on the right, then you’re going to hijack everything. You’re going to hijack the business, the company to fight your battles. When that happens, the ability of companies to carry out their business is severely compromised.

So those three things interacting, I think, have really hit a lot of companies since 2018, not in all industries, but certainly in the creative industries and any industry that hires from elite American colleges.

Brooke: Right, so one point that I’d want to expand a little bit there is that when you talk about the difficulty of businesses for engaging with Gen Zs, there’s one part of that that leans towards employee engagement, but then another section as well that leans towards engagement with clients. Those are both dynamics that need to be kept in mind here.

Jonathan: That’s right, Alison has written so much about this. Go ahead.

Defining “Business Ethics”

Alison: Yeah, so I think Jon has described a number of societal trends. Obviously the three of us have no problem understanding that business sits within society and obviously is affected by these trends. But if you think about the way that business ethics is conceived and operationalized within organizations, I would in general argue that what is called business ethics has very little to do with business ethics. It is rather a set of related but separate functions that are designed to protect the corporate entity from reputational or regulatory risk. So the role of these functions is to provide a shield that protects the organization from these outside forces.

So compliance obviously protects the organization from regulatory oversight. The function that’s called ESG or CSR or sustainability protects reputation by saying, “Look at all the wonderful environmental and social things we’re doing.” Then human resources is also essentially about protecting the company from litigation around discrimination and harassment. Because of the trends that Jon is talking about, those kind of defensive mechanisms are no longer serving the function that they used to. Company leaders need to work on the assumption that anything they say or do is going to become public knowledge, that angry employees might leak it onto social media, non-competes and non-disclosure agreements aren’t as robust as they used to be for that reason. Then there are a lot of angry people, and some of those people are your employees. So all of this speaks to the need to have a very different approach and different concept of business ethics. I think that’s what we’re all struggling with right now, and I don’t think there is that much, in terms of precedent, as to what the solutions might be.

Brooke: There’s one more line that I’d like to introduce here to help us explore that as well as we continue this conversation today, and that’s around some points that Mark Carney has raised with his recent book called Values. What Mark is talking about in that work is the social embeddedness of the economy. So there are certain fundamental pieces of infrastructure that need to be in place for the economy to function at all. There needs to be a sufficient level of trust. So for instance, Mark Carney’s work with the Central Banks, both in Canada and then in England, has been a lot about the trust in currencies and the importance of trust and transparency and some other values for the integrity of the currency overall. He talks about how these pivots since the 1980s towards a dogmatic focus on shareholder value and especially shorter-term shareholder value, has led a lot of companies to take positions that undermine the trust that is necessary for the economy wholesale to continue functioning. Look no further for evidence than the financial crisis in 2007, ‘8, and ‘9, that really threatened to destabilize the entire economy essentially because of the way that ethics was operationalized in industry, as you mentioned, really to protect against reputational risks and to protect against regulatory risks and risks of lawsuits and these kinds of things, but not realizing that actually ethics is something that creates a type of value. Ethical action creates a type of value. In that instance, it’s a type of value that is absolutely necessary. Mark Carney extends that argument to say we’re doing exactly the same thing with regard to the climate, that you can’t have a healthy, functioning market on a planet that doesn’t sustain human life. So we need to be thinking about climate in more than just these kinds of insulation terms, making sure that I can never be held accountable for something bad that my company does. We need to be thinking about it in more positive terms. Perhaps that’s a way to pivot towards this next question. Is remaining neutral an option for anybody?

Neutrality

Jonathan: Well, I think there are a couple separate issues here. So I’d like to first address that I think, yes, we are all alarmed by what happened with the shift to shareholder privacy, and the ascendance of that view from Milton Friedman through then Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, to becoming a dogmatic position for many. I think we all see the problem with business focusing on shareholders. In fact, when I came to Stern, I started co-teaching this class on professional responsibility. I was kind of like a newbie. I’d come to this with new eyes. By the end of the semester, I asked the instructor; “I just don’t understand why everything is about the shareholders who often don’t even know that they own the stock, yet the employees are giving their blood and their sweat. They’re there all the time. Why don’t they matter more than their… I don’t understand.”

It’s this bizarre construction of reality that took place gradually within the business world, and I should say within the academic business world, and intellectuals originally. But I also want to point out that the post-war world was an anomaly. I think many people blame the shareholder primacy movement for everything bad that happened. But from my perspective as a social scientist, we have to look at a number of mega trends and why the post World War II was bizarre and will never be repeated and was wonderful in many ways. That is, first, you had a generation that lived through the greatest trauma that the country had ever been through, other than the Civil War. This had enormous effects of building up social capital. That’s basically the finding of Robert Putnam in Bowling Alone.

The reason why you had all these leagues and organizations in the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s was because those were the people who were influenced by World War II. When the Baby Boomers came along, it’s not that they’re bad people, but they weren’t bound together by the ultimate struggle against evil. As the Greatest Generation retired out and as the Baby Boomers took over, a lot of this would have happened even if we didn’t have the shareholder primacy.

The other thing we had just for a few decades was broadcasting. So the news environment was always terrible. It was always full of lies and partisan newspapers from the 1700s until around the 1910s. Then we get professional journalism from the 1920s through about the 1990s or early 2000s. Now we have it corrupted, in many ways, by partisanship. So for many reasons, the period from the 1940s through the 1970s or ’80s is really unusual, and companies had a sense of one for all, all for one, to some extent. They had a physical location and they would invest in their community. Now with globalization, the loss of the Greatest Generation, the rise of MBAs, I hate to say it, here we are teaching at the Stern School, teaching MBA students, but the rise of this mindset of, “Hey, we can save money for the shareholders if we do this thing which will have external costs on the community.” So there are a lot of reasons why business has changed and why its reputation goes up and down. I just wanted to start with that.

Now to your question about can you stay neutral, I’ve found that a lot of the confusion in our world now, the world is much more confusing than it was 10, 15 years ago before social media changed everything. Alison used the word ‘incoherence’, I think, in her first opening statement. It feels like lots of people are playing very different games on the same field, and we don’t understand each other, we’re puzzled why other people see things so totally differently. Things aren’t working.

So I find it really, really helpful to think for any institution, what is its telos? That Greek word Aristotle used, the telos is the purpose or function. The telos of a knife is to cut. The telos of medicine is to heal. The telos of, I think, of university should be truth rather than social ends. I think it should be teaching habits of thought and research and inquiry, but many at the university disagree with me and think it should be some sort of activism. I would say for business, it’ll vary by industry, but for the most part, it’s creating things of value. It’s doing something very well together that could not be done by individuals, but it must be creating value for its customers ultimately. That’s why business is fundamentally good, because it’s creating things that people need. That actually helps us see why the financial industry is different. But for the most part, your standard business that Adam Smith wrote about or a washing machine factory, whatever it is, I think is fundamentally a good thing.

Now should they stay neutral? I would say, and I know Alison disagrees with me, I would say yes, to the greatest extent they possibly can, because as soon as it becomes normal for businesses to take a position on the issues of the day, then it becomes obligatory for almost all businesses to take positions on almost everything, because some employees are going to push them that way. If the employees in an industry all lean left or all lean right, well then we know exactly what position they’re going to take on every issue.

The whole world, when the culture was confined to talking heads and politicians, it was one thing. But now that we’re actually attacking people in restaurants and we’re shaming them in restaurants because of their public roles, I think that is a terrible flood-in of every part of life with the culture war.

What’s happened since Trump was elected, and understandably, he was outrageous in so many ways. I do understand why corporate America, originally the CEOs were taking sides, but I think we have to pull back on that now that he’s gone, not march forward evermore into the culture war of business.

Alison, for a contrasting view.

Alison: So Brooke, going back to your question of is it possible to be neutral, I think Jon and I would be delighted to dig in further to this question of polarization in the US, but I would answer in a couple of ways. I would answer no. I would give you some examples from the US. The one I always pick is Uber, which there was, as you may remember, I think it was 2016 or ’17, Trump instituted a “Muslim ban”, and there was a taxi driver strike at New York airports.

Uber made a shareholder value-based, neutral decision to keep operating its service during the strike. I don’t believe that Uber saw itself as taking a position one way or the other in making this decision. That decision was not read in neutral terms. Last summer, similarly, the CEO of Coinbase, which is about to list, wrote a letter to his employees saying, and I think he was very affected by having had a lot of employees from companies like Google and Facebook, basically making a less articulate version of Jon’s argument that if you can’t just get along with the core mission of Coinbase, you can leave. That also generated a huge backlash.

So the situation in the US today is such that the middle ground, the neutral middle ground has become a very dangerous place to be. While I agree with many of Jon’s arguments about the way that business is evolving to become a political action is extremely problematic, I do think we need to be realistic about what’s going on and how difficult that is for companies. I also want to briefly talk about the international dimension, because we also saw post the Cold War, the emergence of the Washington Consensus. So business basically went into global markets, and there was a broad consensus driven by the UN and the IFC, etc, etc, saying business can go anywhere. What will happen is the economy will benefit. Society will democratize, capital will have a very good societal impact, and therefore you can justify investing in Russia, China, Angola, Equatorial Guinea, etc, etc.

That era has very decisively come to an end. I spoke to the FT last week about what is going on with human rights law in EU and Europe and the pressure being put on companies who have operations or supply chains in Jingjiang in China, and there are still a lot of people with Chinese names attacking me on LinkedIn as we speak. My comments had nothing to do with the ethics of what’s going on in Jingjiang. It really just made the point that companies are going to really struggle to manage the geopolitical risk between the US and China.

So both the global level and the domestic level, you have found that the kind of neutral consensus has shrunk from being this big ground that we can all agree that business should be on to being a very tiny, fragile little island under attack from all sorts of places.

Jonathan: That’s a great point about the Washington Consensus. I totally agree with you about that, that while it may have fostered faster global development, a rise of GDP, it’s certainly opened up a lot of countries and people to exploitation without proper supervision. You’re also right, I think that of course companies have to take political positions to the degree that they’re wading into geopolitical conflicts. I would not say that it can remain neutral if they are operating internationally like that.

What we’re talking about here is really the crazy public performance culture war arena of taking views because people on Twitter are saying things. You rightly pointed out that Coinbase generated a strong backlash, but here’s the crucial question. What happened afterwards? Because if a bunch of people quit and then they had internal peace and they could all just focus on their mission, well that would show that that’s actually the way to go. You’ll lose a few people but you’re probably better off losing those people, because if you keep them and if you give into them, you’re going to have constant conflict forever and ever. So I have no idea what happened to Coinbase after that. Do you, Alison? Do you have any idea?

Alison: Yeah, I do, what happened was a lot of black and female employees started saying, “Well, in fact, this CEO’s always been totally biased. Here are all the examples of the bias I experienced before I quit.” So things have got worse for the Coinbase CEO reputationally. On the other hand, he is making eye-watering amounts of money, and is about to have an idea-

Jonathan: It’s a good time to be in crypto. Yeah. (Laughter)

Alison: Actually. So I’m not sure how much he cares, but yeah, reputationally, I don’t think things got better for him as a result of this decision.

Jonathan: No, but I mean in terms of the internal culture. No, certainly if it’s that women and people of color suddenly feel much less welcome, okay, that’s a real ethical problem. So it sounds like we can’t really determine anything from the Coinbase case, because it’s such an unusual circumstance. But I would be very curious to know from other companies whether the strategy of really trying to say, “Look, we’re focused on our corporate purpose. We’re not going to do the other stuff,” versus, “Yes. We need to take a stand on these issues.” I don’t know. This is all brand new. The issue has been around for a long time, but in the social media environment, it’s pretty new, and I think I’d love to hear from companies, if people listening to this have experience with a company that went one way or the other, they can say how it worked out. I’d love to hear it.

Brooke: So a couple of nuances that I’d like to unpack there to help move the discussion forward. So first of all, it seems like remaining neutral is probably not an option where whatever is going on kind of intersects with your core business.

Jonathan: Yeah, that’s right.

Brooke: There’s an interesting thought to be had there around what is the core business that companies are in? I read something recently in passing about Facebook’s corporate filings in Delaware, and the purpose of the organization is something like to earn money without breaking the law of Delaware or something like that.

Jonathan: Is that what they put in… That’s in writing?

Brooke: Yeah. It’s not quite as blunt as that, but in line with the legislation. So this idea that you can have a company that is neutral, it’s like, well, at a certain point, you need to be working within certain confines. Like you have a core business. Just in virtue of having a core business, you’re going to bump up against something, and neutrality is probably not an option there. But then there are a whole bunch of issues that will be separate from your core business. There’s potentially a case to be made that you can remain neutral on topics such as that.

The other nuance that I wanted to pull out is, neutral with respect to what? Are we neutral with respect to, or, staking a position with respect to, topics and policy issues? Or are we neutral, or staking positions, relative to people or parties? I think that there’s a really important difference, although it often gets kind of burned down in the firefight that is social media, the difference between who is speaking, be that an individual or a party, and what it is that they’re saying or what position that they’re staking. There I would say there’s hopefully more space for corporations to be staking their positions relative to issues rather than to parties or people.

Employee Activism

Jonathan: Right. It certainly is questionable that they should basically say, “We’re part of the democratic party, and all of our employees must vote for Joe Biden.” That would be a weird thing to say, although some companies might signal that. Depending on the industry, that might be the right move, given your customer base. But I would look at it in terms of just as the Business Roundtable made its statement about retracting shareholder primacy and endorsing a stakeholder view, they made that in August of 2019 just as employee activism was really ramping up for a variety of reasons. So if businesses are going to be taking political decisions, I would want to know. I would want to think systemically. Let’s imagine a country or a world in which businesses take decisions based on careful consideration of the leadership, taking into account all of the different stakeholders with some method of input from all the stakeholders so that they actually know what the average employee thinks and they actually know what their average customer thinks. In such a world, if they make a careful, thought-out decision to support some policy on immigration or the environment that isn’t core to their business, then I could be persuaded that this might be a better world.

We don’t live in that world, and we never will. We live in a world in which, thanks to social media, employers are, I think, mostly afraid of their employees, very similar to how we are on campus. Professors are really mostly afraid of the students, and the students are afraid of the students.

So since it seems as though a lot of the corporate position-taking is based on employee pressures from within, I don’t want to live in that world. I don’t mean the average employee, I mean the ones who are loudest, who tend not to be from both sides, they tend to be from one side, depending on the industry. So I think that would be just terrible for everyone, including the businesses and including the employees, because the employee activists don’t usually speak for most employees. Alison, for a counterpoint?

Alison: Well, interestingly, I agree with you in many respects. Jon doesn’t work that much on sustainability, but what he actually just described is the ideal process for how you should prioritize the environmental and social and governance issues that you focus on. Brooke, as you probably know, there’s this idea currently dominant in the ESG or sustainability field of shared value, which is basically that the business should not go around randomly taking positions on things that the CEO or employees happen to care about, but should focus on areas where the business can both make money and have a positive environmental and social impact. So you look for that overlap in the venn diagram. The way that you are supposed to do that is via a process called a materiality assessment, or you talk to your external stakeholders and your internal stakeholders, and you map issues and you focus on the highest priority issues. That should be done in a consultative, rigorous way. Ideally, you should also address the existential risk to your business.

Now I think what Jon also described in his last answer was more about what is actually happening, which is that businesses, rather than going through that rigorous process and focusing on the most relevant things and being focused and not overly reactive to reputational risk and social media pressure. What you are rather seeing is that this function and this kind of set of activities is treated as the paramilitary wing of the marketing department, and that therefore there is a very reactive, reputationally driven response to issues. So you see very, very knee-jerk and shallow responses, for example, on diversity and inclusion in the followup to everything that happened in the US last summer.

So I think Jon and I are less far apart than you might think, but the issue is in the execution. I will just close by saying that Jon said obviously it’s a terrible idea to write to everybody saying, “Vote for Joe Biden,” as a counterpoint to what Coinbase did. That’s, in fact, what the CEO of Expensify did last summer was to write to all his customers and say, “We think you should support Biden.” That’s not a very good idea.

Interlude

Hi there, and welcome back to the Decision Corner, the podcast of the Decision Lab. I’ve been chatting with Jonathan Haidt and Alison Taylor about the challenge of defining and implementing ethics in the corporate world. So far we’ve discussed the challenge of leading a multigenerational workforce with different values, as well as the radical effect of social media on the corporate world. In the second half of the podcast, we dig into the actual implementation of values that organizations set for themselves, and how to foster a culture where employees feel unified and free to express their values and opinions. Stay with us.

Brooke: If I can kind of sum up what it is that we’ve just been talking about now and pivot us to the next thread of the discussion, we’ve been talking about reading the values landscape that a corporation exists within, and positioning themselves, staking positions or trying to remain neutral within that landscape. What we’ve just been talking about, and I really like that you raised the process of the materiality review, Alison, to think about how a company is kind of creating advantage, both for itself and for wider stakeholder groups in positioning itself in certain places along certain dimensions.

Let’s shift gears now and say, okay, suppose that we’ve gone through this process and we have identified which positions we want to take and which types of value we want to be creating ideally. How does an organization then shift gears and actually start doing the implementation work to create the value that they’ve set for themselves?

Measuring the Effect of Ethics

Alison: Well, one set of thinking is that we need better metrics and better ways of quantifying the benefits. So our colleague, Tensie Whelan, who runs the Center for Sustainable Business at Stern, does a lot of work around the business case and the financial case for various sorts of sustainability initiatives. What she’s really trying to do is to bake this into the core role of the business. So I think that’s one thing.

I tend to be a bit of a skeptic about instrumentalist arguments for these things, because they fall apart very quickly. I think fundamentally, these are more ethical arguments than commercial arguments. I think you need to think very realistically about power and incentives in organizations. You will hear from senior leadership teams, “Yes, yes, yes. We want to think long-term, but quarterly reporting and investors, etc, etc.” So there’s a lot to be done with the investor community and helping them think more long-term. It’s not a coincidence that when Paul Polman took over Unilever, the first thing he did was stop quarterly reporting. Then I think the shift’s underway. I think you need to start thinking about questions of ethics in a less instrumental and more strategic, systemic way, because otherwise, you do get these very reactive, very shallow responses from companies. So we’re starting to see some companies hire a sort of chief integrity officer or somebody that’s not just thinking how can we keep the company from breaking the law? A good example would be Salesforce, who has an ethics lead with a PhD. She does exercises thinking about the long-term implications of product development and their impacts on human rights and the way that they’re developed and that kind of thing. We might also take that approach to the countries that we’re in and where we’re sourcing from and how we’re operating.

Then finally, which it would be bad to miss, there’s a lot of change that needs to happen in the regulatory space. Is it legal? Is it not legal? Do the markets require it? Are still very, very important questions. So really this takes looking at the corporate governance code, the tax rate, what we’re doing on lobbying and political financing, and a whole host of other things where the government really needs to step in.

Jonathan: Yeah, I would just emphasize that it’s the shift away from thinking of ethics as compliance and thinking of ethics as more culture and norms and ethics is, I think, crucial. I think Congress passed some law in the early ’90s that just used the phrase ethics and compliance program. I think they put in a condition that CEO pay is not… Oh no, that was another thing. But the point is somewhere along in the early ’90s, they said businesses can be protected from something or other if they have an ethics and compliance program. They never said exactly what that meant. So as I understand it, in the ’90s, that was fairly quickly built into businesses as a compliance department, because that they could do. That, they know how to do. You have some lawyers, you look at the laws. You just make sure that people don’t break the laws.

When I started Ethical Systems and began to speak to companies, and then we had a lot of interest from ethical compliance officers, and I’d ask them, “What percentage of your work is compliance versus ethics?” They’d say 90% or 100% is compliance. I’d say, “What would you like it to be?” They’d all say 60 or 70% ethics and just the minority of compliance, but they don’t know how to do it, and culture is really hard. It’s very hard to define, it’s hard to measure, and it’s hard to change. Whereas compliance is easier on all of those fronts. But as Alison said, it’s really the long-term thinking. You take the long-term approach, then you can really see the value of an ethical culture. We have research on our page. If you go to EthicalSystems.org and you click on the research, we have a research page on all the research we can find on whether ethics pays. Now research conducted on businesses is often very correlational. It is not very compelling, but there are some that are pretty good, and they almost all seem to show that an ethical culture is associated with better returns. This is even correcting for how companies that are doing very well financially can afford to do all kinds of nice things for their culture. But there’s every reason to believe that if you have an ethical culture in which people trust each other and they don’t have to spend a lot of resources on verification and cheating, that such a company is going to be more cooperative and more productive and employees will be more motivated. We know that. That employees are much more motivated and happy when they work at a company where they can trust their coworkers and their leadership. So yes, we do think, and that’s part of our value proposition for companies at Ethical Systems, is that good ethics is ultimately good business.

Ethics for Aesthetics

Brooke: So there’s a personal anecdote that I want to pull out here as a way to flesh out some of the types of things that we can do here. So for instance, in a previous job, one of the first things that I had to do in signing a bunch of paperwork during the onboarding process, one of them was the code of conduct, code of values, and this is what the organization stands for, and supposed to put your signature at the bottom of the page saying, “Yes, I stand for this too.”

Essentially, after putting my signature on that line on the very first day, I never heard anything about it again. What that really showed me, now looking back on it retrospectively with my ‘behavioral eyes’, is that this is something that is treated as a guardrail. It’s something that must not be transgressed, but it’s not treated as a kind of a center for value creation. Abiding by these kind of codes and these behaviors isn’t something that the company considers to create more value the more that you do it, because if they did, then they would be creating incentives for it, and it would just be much more visible and much more salient in people’s everyday work. So for instance, there’s lots of talk about how to effectively incentivize the stuff that you want your employees to be doing more often, because every additional widget that they create or whatever you want to incentivize, creates more value for the company. But we don’t treat ethics or values in that way. We generally treat them as this kind of limit case, which is very not salient, and therefore hard to measure whether we’re within bounds or out of bounds in any particular moment. But there are very clearly those things that we do want to incentivize in this linear way. So what are some of the other tools that we can use to help to increase the salience of this and create the ecosystem where people lean into those values because it’s good for the business?

Jonathan: So I think you said that it’s treated as a guardrail. I would argue based on what you said, it’s not even treated as a guardrail, that as Alison said, the real goal is just liability protection. So they’re just trying to show that they just want to be able to document that they showed this to you. If they really treated it as a guardrail, then they would be reminding you of it and then doing all sorts of things to keep it in play, but they’re not. So it’s just an exercise in liability protection, I would think. Secondly, to the extent that people have thought about culture and incentives, even just the word incentives kind of clues you in that these are people who take a homo economicus view. That is they’re either economists or lawyers who think, “Well, if we want a certain outcome, then we should pay them more for that outcome. Let’s hook the bonuses up.” Everybody understands if you give bonuses based on a certain behavior, you’re going to get more of that behavior. There’s a famous paper in management called ‘The Folly of Hoping for A While Incentivizing B’. We want ethics, but we’re going to give you a bonus for doing something else.

So part of what we’re doing at Ethical Systems is we’re bringing in social psychology. There’s kind of a famous saying in social psychology attributed to a well-known social psychologist, Bob Zajonc, that cognitive psychology is social psychology with all of the interesting variables set to zero. A lot of people have read Dan Kahneman’s book, ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow’. He’s a brilliant Nobel Prize-winning cognitive psychologist, and he shows all of the biases of thinking and reasoning and decision-making, but he doesn’t bring in the social stuff that much. That was great when it started in the ’90s. Well, Kahneman was doing this at the beginning of the ’70s, he was a real pioneer. But I think now we’re ready to really be bringing in the social. People care a lot more about their reputation than they do about a few thousand extra dollars of bonus. That’s part of what we’re doing. So we have one of the best economists who really brought in social psychology is Robert Frank at Cornell. So he is one of our collaborators, and we have a bunch of social psychologists; Francesca Gino, Dave Mayer, Linda Treviño. So we’re really trying to take into account what’s really operating on a person? People really want to be thought well of, they want to get along, they copy each other’s desires. If you bring behavioral science into culture design, you can do a much better job than if you just have a bunch of economists deciding what incentives to give on what schedule.

Brooke: Yeah, that’s so interesting. A discussion that we had here at TDL in the last few months was thinking about our own incentive structures here internally. One of the things that we do is when we kick off and when we finish a big new initiative, we have a bit of a celebration. Obviously in COVID times, that’s a very different beast than it once was, but at some point, someone kind of remarked off the cuff like, “Yeah, it’s great that there’s this incentive, but the thing that I really look forward to is just this opportunity to get together with all of our team and celebrate and have fun, because we like the people that we work with.”

Jonathan: It’s almost as if people cared about that more than money. (laughter)

Brooke: Yeah. (laughter)

The Ethical Role of Behavioral Science

Jonathan: Actually, so I’d like to ask you, at TDL, I know you care about and you try to bring in behavioral science. Just give a sense in what way? What kinds of theories, or how do you use social science to help businesses?

Brooke: Yeah, so some of what we’re looking at is just businesses who come to us and say, “I’m seeing outcome A, and I want to see outcome B, and I don’t understand why it’s not happening. I put more money in the pot towards B, but people still do A.” The kind of classical or the typical economic thing of just put more money in the place you want to see people hasn’t worked. So now we’re at a loss. So what we look at is both cognitive and social dynamics there. So I think the point that you raised earlier about the genesis of behavioral science being really, I think, led at the vanguard from the cognitive side, but now also needing to fill that in with the social side. That’s something that we are trying to take seriously and to bring into our practice. In fact, a lot of the podcast guests that I’ve been interviewing this year and towards the end of last year are really focusing on that social element and thinking about the lived experience of people inside a group and how those dynamics change. So thinking about how empathy, for instance, changes people’s behavior.

Jonathan: Can you give us an example? How do you actually use empathy? Empathy is such a popular word in psychology, and it resonates on the left but not the right, generally. Give me an example of how a company can use empathy or how you could foster it.

Brooke: Yeah, so one of the things that we’ve seen, for instance, in some of the work we’ve done with digital platforms is looking at empathetic calls to actions. So wanting to really emphasize that when a user arrives on a website, the way that the website articulates the value that it’s offering to them should really be expressed in the same terms that the users themselves use to think about their own challenges, and that that’s a way to help to clarify to them that we understand who they are, and we take seriously their challenges. We’re not imposing our logic and our perspectives on them. We want to be more receptive to what it is that resonates with them.

Jonathan: So does that mean that businesses could get information on people who come visit their site through various behind-the-scenes techniques and they could modify what’s on the home screen when different kinds of people come?

Brooke: Yeah. So that’s some of the types of stuff that we do-

Jonathan: That sounds very empathetic. (laughter)

Brooke: Yeah, part of it is also that you need to think about what objectives your user base is seeking there. I would say at its worst, behavioral science is applied in this extremely instrumental way where you say, “I’ve already decided what service I’m going to offer and what price point and all these kinds of things. At the very last minute, just before I cross the finish line, I’m going to stretch over this beautiful cover of behavioral science. I’m going to candy coat the pills so that it goes down easier.” That really is the antithesis of what we do. We really think about behavioral science as a way to learn about what the needs are of clientele to then kind of squirrel away behind the scene and say, “Okay, what is the most valuable value proposition that we can articulate for those people? What is the most valuable thing that we can do for them? Not just what is the most valuable way that we can articulate what we’ve already decided we’re going to.”

Jonathan: Right, right. Well, that fits in with my observation when I moved into the business school world, that most of the social psychologists are in the marketing department. Businesses have long known to do experiments in marketing. That they’ve been doing for a very long time, AB testing on that wrapping that you put on at the end, and art of what we’re trying to do at Ethical Systems is get people to take that experimental approach about management and especially culture. Of course, there have been psychologists in the management department for a long time. Some of the early behaviorists back in the 1920s and ’30s were trying to help companies. Increased productivity was always the thing, but I see what you’re saying. I see what you’re doing, and yes, to the extent that you can bring psychology and kind of a human-centered focus to every aspect of product development and management and production and marketing, I think a company would be better off. Alison, what do you think of that? Or what do you see about companies using psychology or behavioral science?

Alison: I think exactly as you said, it’s usually used for marketing or maybe improve management decision-making that has been for all the reasons we’ve discussed already, quite a lot of resistance to using experiments to improve ethics or to improve culture, because as we’ve already discussed, the role of business ethics functions is less ethics than showing that we have a good program that the regulators will be happy with. So very, very performative. It’s also fundamentally not great to go to regulators and say, “Well, we thought we’d experiment rather than taking your advice.” So historically, I think this has been quite a hard sell, but due to all the shifts going on, and we can just think about remote work, we can think about the increased focus on diversity and inclusion, we can think about new expectations that younger employees have of leadership, just to go back to Jon’s original point. A lot of the problems that companies are grappling now in their ethics, very broadly defined, are without precedent in terms of solutions.

So now is a really wonderful time to be doing this kind of work, and I’m really just seeing more and more energy on this in the public domain, and very much, even more positively, this focus to group dynamics rather than just individual cognition, which has really been the missing piece. We’re very individualistic societies. Obviously the US and Canada, we don’t like this idea of how influenced we are by people around us. I think this has really stymied research, but everything that’s happened in the last few years, whether it’s more awareness of systemic racism or COVID or climate change, has really, I think, re-focused people on how important group-level dynamics are. So maybe this is the perfect opportunity to try and really advance this field.

Brooke: So you raised two important challenges there. The first is coming to terms with our interdependence, and the second is around experimentation. So one of the things that we’ve experienced is that typically if someone approaches us about a piece of work that’s strictly marketing-focused, you know, “help us to optimize conversion on this”, there also seems to go along with that, a culture within the organization that marketing is all about push-side pressure. Marketing isn’t about learning about your client. Those kinds of changes in the dynamics within organizations where we have to ask ourselves, “Well, where does that function live to learn about our client?” That’s a very, very difficult conversation on the corporate transition required to really center that function of learning about clients and learning about them not just as individuals, but as members of societies. It’s a very, very difficult transition for organizations to undertake.

Alison: Yeah, though one of the other reasons we could say that all this stuff is going on, I’m so fascinated by this, is the shift from how companies make money, which used to be very tangible things, buildings, plants, machinery, people, and is now, to a very great extent, intangible factors like branding, R&D, reputation, employee engagement, all of which means that if you make a decision to invest, the outcome, in terms of the value created, is much less linear and much less direct. So all of this requires really, a very profound shift in how you think about leadership, management, engagement with society, etc. I would fully agree with you, Brooke, that most organizations aren’t ready for this, but yes, marketing should change. Ethics should change. Leadership and government should change. I honestly think that the companies that can adapt to this new way of thinking will be the ones that survive into the long-term.

Practical Steps to Take

Brooke: So on that note of helping our listeners to create the competitive advantage of which they are so desirous, if you’ve been listening to this conversation and you’ve just been drinking it up, what’s something that you can start doing right away to start making progress on these matters? Jon, I’ll ask you to start there.

Jonathan: Okay. Well, I would say that if you want to make change, and especially systemic change, we’re not talking about just priming people to think about something in the short-term, then I think you and your leadership team should have kind of a common vocabulary. You should have some conception of why, what are you after? Why is culture so important?

So if there’s one thing to do, I would say it’s go to EthicalSystems.org, click on the research tab, let me guide you to a particular page. I would say I think that would go to corporate culture. Maybe start with corporate culture. We have book summaries. We’ve got research summaries. We have all kinds of materials there, because we find most people, they do quickly get or they were already there thinking that culture is so important. So many people in business know the maxim that ‘culture eats strategy for breakfast’.

But you don’t want to just be flailing around trying different things. You want to do this as a team and draw on the social-science in part so that you can improve your thinking about whatever your particular challenges are.

Brooke: Alison?

Alison: I think measuring your culture in a rigorous way is a very, very good starting point. I know that a lot of companies, back to your point about codes of conduct, Brooke, are looking at shifting to more principle-based codes of conduct. They’re revisiting their purpose and mission. They’re doing that in a lot of consultation with employees. One of the ways that you can avoid some of the toxic conflict over polarized issues that we discussed would be about having a conversation about principles, and it doesn’t need to be, “Oh, we’re going to work with oil and gas companies.” It has to be, “How do we make decisions about who we do business with? Are you able to withdraw if you are personally uncomfortable?” If you can set some principles in a collaborative way, find ways to listen to all your employees, not just the loudest and most opinionated. I feel like this is a conversation I have three times a week of “we cannot sort the signal from the noise”. Only the people with really extreme views and positions turn up and show up. So you have to provide anonymity and psychological safety.

But I think from talking to my students, they can understand that businesses need to make money. I don’t think they’re obsessed with doing this stuff for the sake of it. I think a collaborative revisit of the code of conduct where you make it more salient and you’ve set some principles and you’ve set a way forward, and then you pursue that way forward and don’t get distracted, that would be a very good start.

Brooke: Yeah, I really like that idea that you have to start from where you are, but you also have to start from the people that you have. With culture, just as with strategy, you’re not in a vacuum. You have a certain product or a certain service already out there in the market. You have a certain reputation. You have a certain client base that has certain expectations of what you’re going to deliver.

Similarly, you have a certain set of employees on hand in the roles that they are. You have a certain set of values that have been articulated the way that they have. You have to consider your history as you move forward. So I really like the way that you formulated that and that it needs to be an inclusive discussion and one that manages to get past just the loudest voices, and especially that issue of psychological security I think is really, really important because we’re so primed to feel that everything is going to become public that psychological security is so low at a baseline. We probably need to bend over backwards to make sure that people know that there’s going to be some security and some kind of safe space around this conversation.

Alison: I absolutely agree. I think this is a huge problem, and it speaks, again, to this very reactive, reputational-driven kind of norms that we have. I think you see it both internally with companies panicking if they get critiqued. You also see it externally with a very shallow reaction to getting criticized on whatever the issue is of the day. So all of this is solved by long-term thinking. That’s an easy thing to say. It’s a very, very difficult thing to do. But psychological safety is a good principle, I think, to proceed on.

Brooke: All right. That’s great. Alison and Jon, thank you so much for today’s discussion. This has been wonderful.

Jonathan: Our pleasure, Brooke. Thank you.

We want to hear from you! If you are enjoying these podcasts, please let us know. Email our editor with your comments, suggestions, recommendations, and thoughts about the discussion.