Communicating During The Coronavirus

The “unprecedented new normal”

It would be safe to say you’ve been on a successful digital detox if you haven’t seen at least one of the following in the past week:

- The Google trends image about how search trends for the word “unprecedented” have been unprecedented

- An article about the “new normal” and how consumer behavior will change

- An easy-to-make sourdough recipe

Unfortunately, we have not yet seen the end of these trends. For many months (or perhaps even a couple of years to come), we will all be discussing this “unprecedented” twist our lives have taken and how we’re dealing with our new normal.

Never before in our lives have organizations and governments had to respond in such short notices to changes taking place around them. And they will have to continue doing so over the next few months by informing us about changes to their services, reminding us about safety measures we should adhere to, and ensuring that the inconveniences we might face are for our own good.

Arguably, none of these are easy to communicate — but understanding how people perceive risks and the psychology behind how people react in these situations can help us create a more effective communication framework.

Behavioral Science, Democratized

We make 35,000 decisions each day, often in environments that aren’t conducive to making sound choices.

At TDL, we work with organizations in the public and private sectors—from new startups, to governments, to established players like the Gates Foundation—to debias decision-making and create better outcomes for everyone.

How we perceive risk

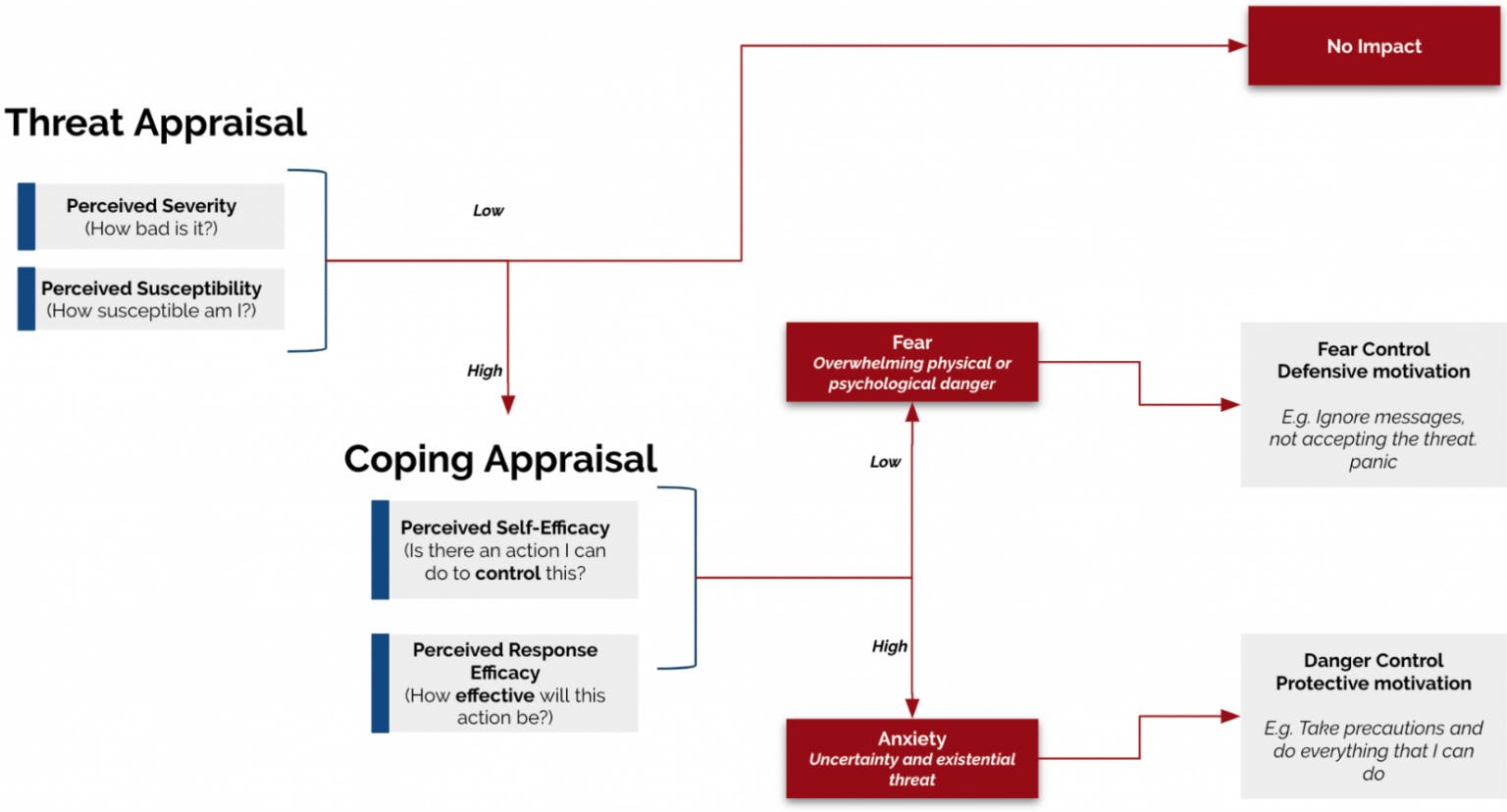

Social scientists and psychologists have been fascinated with risk perception for the longest time. The Extended Parallel Processing Model gives one framework that describes our range of responses to risk.1 To put it simply, this model explains the process that helps people assess a message about a given risk. When a message is received, people evaluate it at two levels:

- The perceived threat of the risk: This is derived from how severe the risk is perceived and how susceptible one feels to the risk.

- The perceived efficacy: This has two parts – how one feels about their ability to respond to the threat and how effective that response will be.

As shown in the framework, a low perceived threat would lead to no reaction. A high perceived threat, coupled with a low perceived efficacy, would lead to “fear control,” which often results in the message being ignored. An example of this would be the horrifying stories of people going on spring break holidays, in defiance of recommendations from health officials. The perceived threat of the risk here is high because stories of rising cases are plentiful. The simple idea of staying at home might seem difficult and ineffective for a young person in college living life to the fullest around friends. This idea leads to a “defensive motivation” approach —“I would rather just ignore this threat and enjoy my spring break.”

Source: Adapted from Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model2

A high perceived threat, with a high perceived efficacy, would lead to “protection”, where the individual does everything in their power to control the situation by following precautions. For instance, wearing a mask or maintaining physical distance. In this case, the threat appraisal is high, but people believe in their ability to control the risk with small steps such as wearing a mask, and hence, put themselves in the “protective motivation” approach.

While this is easier said than done, communications do play an essential role in this assessment. Whether someone reacts with fear or anxiety (or does not react at all) could be driven by how risk and coping mechanisms are communicated to them.

Framework for Communication:

Based on behavioral science concepts, here are some ways to communicate better during the pandemic. This is not an exhaustive list, but a good starting point to analyze communications.

1. Transparency: Some of the most intense discussions around COVID-19 have been around false information. One golden rule of communication is that if you don’t communicate, people will assume. And when people assume—especially when they are in fear—they will only assume the worst. It is thus essential that businesses and governments are open and transparent about facts. For example, the Government of Singapore has received praise from the WHO2 for its transparent information sharing through Whatsapp and Telegram.3 By doing so early in the crisis, the government built trust, which allowed them to communicate sensitive messages more effectively.

Presenting the right information in the right way also lets the receiver perceive the risk more appropriately. For instance, using the flu as a reference turned out to be a poor way of getting people to appraise the risk of COVID-19 because the flu is a known and smaller risk.

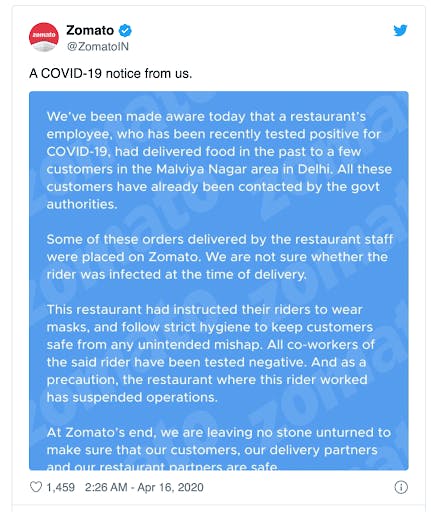

In the next few months, people may need convincing when it is time to return to normal; and in this time, information and transparency can play a critical role. If Chinese food delivery apps are anything to go by, this indeed is true. From showing the temperature of the delivery person on the app to giving people factual information when a case surfaces in the service industry, businesses must be prepared to be truthful.

Indian delivery app Zomato coming forward with news of delivery person being infected

Source: Twitter5

2. Shared Values: It’s an understatement to say that our generation has never before faced an existential threat like COVID-19. And threats like these that are as impactful to all of humanity can lead people to have feelings of collective angst.6 This can result in good, such as when people have feelings of selflessness in which they wish to do everything they can to help society. It can also lead to negative consequences, as we saw with the case of panic buying.6 To channel this emotion the right way, businesses and governments need to bring up shared identity, so that the risk of an existential threat is seen as something people can cope with.7

Shared identity here refers to a sense of connection people feel to each other through shared experiences, interests, or even common sufferings. While the shared experience of being in a pandemic may be strong enough to evoke the feeling of being connected as many of us move on without getting infected, this shared value may be insufficient alone. Getting people to act in the interest of the whole group’s safety might prove to be even more challenging in such a scenario. Communication will then play a crucial role by reminding people of a shared identity when it does not exist.

The AI Governance Challenge

The Budweiser One Team campaign is an excellent example of doing just that. In light of the COVID19 crisis, the parent company of Budweiser, Anheuser-Busch InBev, redirected $5 million of its sports and entertainment marketing spend to the American Red Cross to support the fight against the pandemic.⁸ The One Team campaign shared this information with viewers through a compelling video. While there have been criticisms about brands jumping on the COVID-19 bandwagon, Budweiser jumped on it with great insight—by understanding that their consumers want to belong to and support sports teams. By showing sports teams composed of everyday COVID-19 heroes, they built a new shared value.

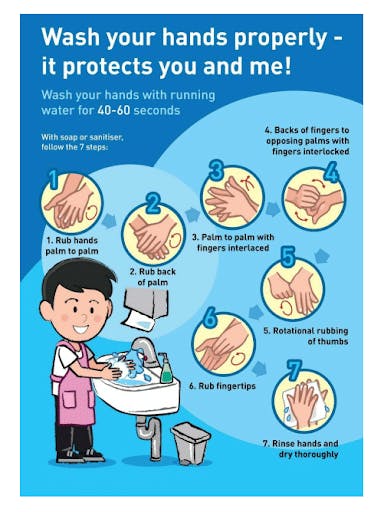

Another example of using a shared value to channel emotion the right way is the case study of hand-washing communications shared by the Behavioral Insights Team, a social purpose organization that applies behavioral science to public policy.10 The team tested seven hand-washing communication posters (that each originated from different countries around the world), with 2,629 respondents in the UK. The most effective poster turned out to be one made by Taiwan. Take a look and see how impactful the use of “you and me” is in the first line of the poster.

Taiwan CDC Handwashing campaign

Source: BIT10

3. Social Norms: One aspect of communication that has worked well for a long time is the use of social norms in nudging behavior. Now more than ever, we need to remind people about the norms they should follow. Once the lockdowns end and people try to get back to their lives, the pandemic might not be as great of a focus as it has been thus far; and yet, we still will need people to adhere to safety regulations. This is important for the risk coping appraisal to be a success and for people to feel confident in their ability to keep themselves safe. One way to do this is to make the new norms more salient. Celebrities and leaders adopting new techniques for greeting each other—such as using elbow bumps to say hello—is an excellent example of this.11 Communicators will need to assess how to make new norms common, accessible, popular, and easy to follow. Behavioral design lessons might come in handy here, especially if adopted to the cultural contexts where they are implemented.

While this list of ways to communicate is in no way exhaustive, it is a starting point for organizations and governments to start thinking about how to address their audiences in our new normal. As we brace ourselves for hard times, we must remember that communication is one thing that will always remain with us. With science-backed insights about how people react to risk and what we can do to help them, we might just be able to convert communication into a strength that no virus can touch.

References

- Witte, K. (1992). Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Communications Monographs, 59(4), 329-349.

- https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/coronavirus-who-praises-singapores-containment-of-covid-19-outbreak

- https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/singapore-south_korea-taiwan-used-technology-combat-covid-19/

- https://twitter.com/DerekjAndersen/status/1247976394925064192?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1247976394925064192&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.hindustantimes.com%2Ftech%2Fcovid-19-china-is-mass-tracking-body-temperatures-and-we-need-this-in-india%2Fstory-Mb2uFAvUJGKe2KpoLYg5tO.html

- https://twitter.com/ZomatoIN/status/1250490786896121856?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1250490786896121856&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Feconomictimes.indiatimes.com%2Fnews%2Fpolitics-and-nation%2Ffamilies-in-south-delhi-isolated-after-delivery-boy-tests-positive%2Farticleshow%2F75175022.cms

- Van Bavel, J. J., Boggio, P., Capraro, V., Cichocka, A., Cikara, M., Crockett, M., … & Ellemers, N. (2020). Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response.

- Reicher, S. & Haslam, S. A. Beyond help: A social psychology of collective solidarity and social cohesion. in The psychology of prosocial behavior: Group processes, intergroup relations, and helping 289–309 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010).

- https://adage.com/article/video/behind-budweisers-one-team-coronavirus-response-ad-age-remotely/2246781

- https://herviewfromhome.com/living-budweiser-ad-one-team/

- https://www.bi.team/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/BIT-Experiment-results-How-to-wash-your-hands-international-comparison.pdf

- https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/magazines/panache/the-ritual-handshake-loses-its-grip-in-the-time-of-coronavirus/articleshow/74803182.cms

- https://qz.com/1836247/social-distancing-markers-from-around-the-world/

About the Author

Preeti Kotamarthi

Preeti Kotamarthi is the Behavioral Science Lead at Grab, the leading ride-hailing and mobile payments app in South East Asia. She has set up the behavioral practice at the company, helping product and design teams understand customer behavior and build better products. She completed her Masters in Behavioral Science from the London School of Economics and her MBA in Marketing from FMS Delhi. With more than 6 years of experience in the consumer products space, she has worked in a range of functions, from strategy and marketing to consulting for startups, including co-founding a startup in the rural space in India. Her main interest lies in popularizing behavioral design and making it a part of the product conceptualization process.