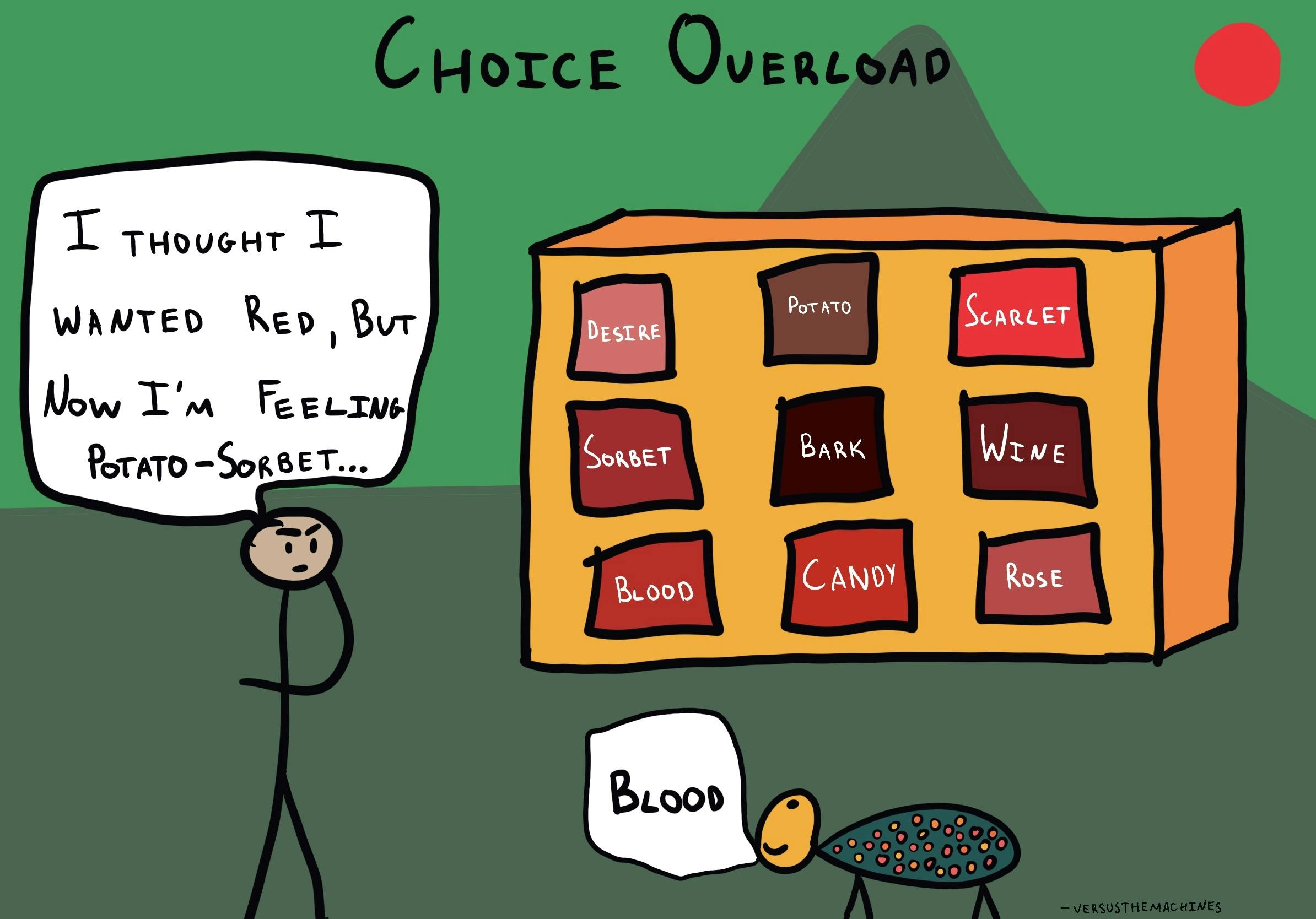

Why do we have a harder time choosing when we have more options?

Choice Overload

, explained.What is Choice Overload?

Choice overload, also known as overchoice, choice paralysis, or the paradox of choice, describes how people get overwhelmed when they are presented with many options. While we tend to assume that more choice is a good thing, research has shown that, in many cases, we have a harder time choosing from a larger array of options.

Where this bias occurs

Imagine it’s a hot day out, and you decide to pop into an unfamiliar coffee shop. As you get in line and look at the menu boards, you’re bombarded with a whole slew of options. Should you get a simple iced coffee or a Frappe? What flavor? But wait, the Frappes are so expensive—you should just go for a tea. But that has less caffeine and will give you less energy! What to do? By the time you get to the front of the line, your head is spinning so much that you just grab a bottle of water. You walk out, regretting that you didn’t get something a little more exciting.

Debias Your Organization

Most of us work & live in environments that aren’t optimized for solid decision-making. We work with organizations of all kinds to identify sources of cognitive bias & develop tailored solutions.

Related Biases

Individual effects

Choice overload can cause us to delay decision-making, considering the many options available is taxing on our cognitive systems. Having more options also leads to decreased satisfaction, lower confidence in our choices, and a higher chance that we will regret our decisions.1

Systemic effects

We are not only susceptible to choice overload by being consumers, major life decisions, such as our choice of career and our choice of romantic partner, are also subject to its effects. With near-infinite choices in almost everything, many feel preoccupied with making decisions or ruminating over choices we regret.2 This may have consequences for our mental health, playing a role in depression and anxiety.

How it affects product

If a product has too many variations, consumers might find it challenging to differentiate the features that make each item unique.

However, this is not always the case. Researchers Chernev, Bokënholt, and Goodman found several moderators that affect the impact of choice overload: the complexity of the choices, how difficult the decision is, preference uncertainty, and decision goal.13 What’s interesting is that some items elicit choice overload while others don’t. For certain products, we want more options. Research on souvenir shopping suggests that we are not bothered by the excess of choice – shoppers were satisfied with the items they picked and didn’t experience any regret about their purchases.14

Choice overload and AI

Artificial intelligence can help to mitigate choice overload, specifically for maximizers (those who exhaust every option looking for the best). When AI is used to power search engines, users are presented with the top-performing sites. This limits the number of options individuals have to search through to find exactly what they are looking for.

AI-powered recommendation software also helps to limit choice overload. When scrolling through abundant streaming services, choosing a show seems nearly impossible. By the time you are done surfing through the myriad of options – looking for that one perfect movie – you may not even feel like watching it anymore. However, certain platforms include a recommended tab, reducing the selection of 500+ to a handful of options. Recommendations are based on your streaming behavior and align with content you already consume, increasing your odds of satisfaction.

Why it happens

Having lots of choices is one of the biggest things that separates our modern existence from the lives of our ancestors. Until very recently in human history, most people’s life paths were more or less predetermined: few individuals had much say in what job they would have as an adult, whether they would get married, or whether or not they would have children. In a harsh and unforgiving environment, being picky about what kind of foods you would eat or how you dressed could result in you winding up dead.

Life in the modern world couldn’t be more different. Industrial and technological advancements have made it possible to manufacture more and more products and to import others to regions they would never have reached before. We have shifted to a free market economic system, where alternatives proliferate and compete with one another, and, at least in the Western world, we have evolved culturally to prize individual freedom and autonomy over nearly everything else.

There is a widespread assumption that more choice equals more freedom, which many regard as a positive. But the empirical evidence on choice overload contradicts this idea. In many cases, more variety makes our lives harder and less pleasant. As psychologist Barry Schwartz has argued, our approach to life is so rooted in individualism that we struggle to see how choice overload harms us. The effects of this bias go beyond complicating our decision-making process: it also has a significant impact on our emotional experience, decreasing our satisfaction with the choices we make and increasing the likelihood that we will regret those choices.

We have limited cognitive resources

Choice overload gets its name from the paralyzing effect it has on our decision-making processes: the more variety there is, the harder it becomes for us to choose. Not only does this make the experience feel more draining, but it also makes us more likely to choose nothing—to put off making a decision entirely because we feel overwhelmed.

In a study on the effects of choice on motivation, researchers set up a jam-tasting booth at an upscale grocery store. On some days, they displayed a limited selection of 6 flavors; while on others, they showcased extensive assortment of 24 flavors. Customers were allowed to taste as many jams as they wanted. Participants were then given a coupon, offering them a discount on the jam. The coupons were coded so that the researchers would know which customers had cashed them in. In the end, 30% of customers who visited the smaller booth returned to buy some jam, compared to a meager 3% of customers who saw the booth with the larger selection.3

This finding is counterintuitive: most people would expect that, with a larger array of jams available to them, there would be a higher chance that customers would find an option they liked and thus, would be inclined to return But in actuality, more choices just means more decisions that we have to make, and making decisions uses up mental energy—of which we only have a limited supply. When we don’t have the cognitive resources to weigh our options, we can end up simply abandoning the effort of making a choice. Research has also shown that when the decision is made more difficult—for example, by adding time constraints or choosing products that differ from each other on many different variables—people experience greater choice overload.1

The more choices, the higher our expectations

Alexander Pope once said, “Blessed is he who expects nothing, for he shall never be disappointed.” As we have all experienced at some point, great expectations can be toxic to our actual experience of the world: the higher our expectations, the easier it is for us to be let down when reality doesn’t measure up.

Research has shown that this mechanism, known as “expectation-disconfirmation,” is a big driver of choice overload. The more options we have to choose from, the more confident we are about identifying exactly what we are looking for. Because of this, our expectations are set higher than they would have been if given fewer options.

There is experimental evidence to back up this claim. In one study, participants were asked to select a camcorder for a coworker. The coworker had specific preferences for the camera’s weight, resolution, memory, and zoom. Participants were given a catalog that included either 8 or 32 different camcorders to choose from. After they picked a model, they filled out questionnaires about their experience. Participants were asked about how their chosen camcorder measured up to their expectations, giving it a rating on a scale of 1 (“much worse than I expected”) to 9 (“much better than I expected”).

As expected, participants who received the larger catalog experienced more choice overload and were less satisfied with their choices. In other words, the more products people had to choose from, the worse they felt their chosen camcorder stacked up with their initial expectations.4

We can be maximizers or satisfiers

We all know people vary widely in their personalities, so it’s no surprise that they also take various approaches to making decisions. Some people are what we call maximizers: people who feel compelled to search until they find the best option available. Maximizers must compare all their choices and evaluate alternatives on a whole host of attributes before they feel ready to decide. Other people are satisficers: folks just looking for something that meets their basic requirements. Satisficers are content with good and don’t feel the need to seek out the best.5

Maximizing isn’t inherently bad: it can lead people to compare all their options more systematically than they might otherwise, which can help them make more informed decisions. But in a world of near-infinite choice, maximizing can create several problems, driving us to seek out more and more alternatives for our consideration—and pushing us into choice overload. Meanwhile, satisficers aren’t necessarily bothered by an abundance of options because they have no compulsion to research each one of them.6

We don’t always know exactly what we’re looking for

On the flip side, preference uncertainty fuels choice overload: not knowing exactly what we are looking for. If we don’t have much knowledge about the things we’re trying to choose from, it becomes overwhelming when faced with a huge assortment of options. Supporting this explanation, research has shown that when consumers are considered to be experts in a domain, the effect of choice overload is reversed: people who are certain about what they are looking for have a harder time when they have fewer options, not more.1

One study conducted by Maureen Morrin and colleagues, looked at enrollment rates in 401(k) plans. When investors with low levels of financial knowledge were offered a larger number of funds to choose from, about 65% of them decided to participate in one—compared to 88% of people with high financial knowledge. When people were offered a small number of funds, the numbers were reversed: 65% of high-knowledge investors participated, while 80% of low-knowledge investors did.7

Why it is important

Choice overload makes it harder for us to make decisions, and it can make us feel so overwhelmed that we just give up, putting off the choice until later. This can have serious consequences if it leads us to procrastinate on important decisions indefinitely.

The 401(k) study, illustrates decision procrastination. As of 2012, it was estimated that 10% of American adults didn’t actively save for retirement. For low-income households, this number was even higher, at 21.6%. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, more than half of workers in the US had access to a contribution plan in 2006, but 21% of those people chose not to participate.7 If, as Morrin and colleagues’ research suggests, a significant number of those workers put off enrollment because of choice overload. This same may be true for other essential services, including healthcare providers, that have seen an explosion of choices in the past few decades.6

(Un)Healthy choice

According to psychologist Barry Schwartz, a leading researcher in this area and author of The Paradox of Choice: Why More is Less (2004), the bottomlessness of our choices may actively harm our wellbeing, and might even contribute to depression and anxiety. Schwartz argues that, because we are now faced with so many choices, big and small, we spend an increasing amount of time and energy simply being preoccupied with decisions—decisions we will have to make in the future, and ones that we have made before and now regret.

Although there isn’t causal evidence for this claim, the research is clear that choice overload does lead to negative emotions and stress. Schwartz's research has also found that maximizers (as opposed to satisficers) are less happy, less optimistic, and more depressed. One study found that the people who maximized the most had depression scores in the borderline clinical range.6 And that was nearly 20 years ago—in the age of social media and FOMO, many would argue that the compulsion to maximize has only become more widespread.8

How to avoid it

Although choice overload is a strong and pervasive bias, steps can be taken to reduce its power over us. With discipline and planning, the decision-making process can be tweaked and we can avoid feeling overwhelmed.

Give yourself time just to browse

Having lots of choices isn’t all bad—as a consumer, you should take the time to research and compare alternatives. However, problems arise when individuals try to learn about all of their options at the same time that they are making their choices (as maximizers do).

Studies have shown that intention matters. In choosing between many options, we are less likely to feel the effects of choice overload when we don’t put any pressure on ourselves to commit to one option.1

Instrumental choice makes us prone to choice overload by undermining our cognitive resources. In one study, people who chose vacation packages with the goal of preparing for an upcoming vacation later performed worse on a cognitive task compared to people who chose vacation packages just for fun. Experiential choice also leaves people feeling more energized and more motivated than instrumental choice.9 All of this suggests that it’s helpful to do some dedicated “window shopping.” Take some time just to browse and learn about your options—and set a firm rule for yourself that you will not buy anything during your browsing period, or make any final decisions. Though it may be hard to completely separate these intentions, this will not only help to avert cognitive overload; it will also help you get more enjoyment out of the experience.

Make your choices “final sale”

A big component of choice overload is regret: the nagging feeling that we’ve chosen the wrong option, and made a huge mistake. When the decision we’ve made is reversible—for example, when we have the option of returning a product to the store or exchanging it for something else—choice overload causes us to agonize over whether or not we should renege on our choice and often drives us to do so.

In Paradox of Choice, Barry Schwartz writes that treating your choices as nonreversible (even if they technically are) can shut down this process before it gets started. Whether you’re choosing a restaurant for dinner or deciding which house to buy, once you’ve committed to an option, fixating on all the shortcomings of your pick will only bring misery.

Schwartz illustrates this by recalling a pastor’s sermon about romantic love, where the pastor acknowledged that the grass is always greener. As we go through life, there will always be people who are more appealing than our significant other in some way: people who are younger, smarter, more attractive, and so on. If we allow ourselves to, we can get caught in an eternal sandtrap of regret and FOMO, feeling like we’ve made a mistake for not choosing the “best” person to spend our life with. If we want to be happy, we have to simply tell ourselves that we’re not going down that road; we’ve made our decision and committed to somebody, so that’s that.6

Keep a gratitude journal

Another (somewhat cliché) recommendation from Schwartz’s book is to cultivate a mindset of gratitude. Choice overload can blind us to all the positive aspects of the things we’ve chosen, nudging us to obsess over their shortcomings instead. This robs us of the joy of experiencing these things as they are. Making an active effort to be thankful for the things we have can be a powerful tool to break out of this tendency.

Schwartz acknowledges that gratitude doesn’t actually come easily to most of us—it’s a thing we have to practice.6 One simple way to practice is through regular journaling: keep a notepad by your bed, and at least once a day, write down five things that have happened that you’re grateful for. It might seem twee, but by making this a regular habit, you can shift the focus of your attention to the positive, and avert the emotional consequences of choice overload.

How it all started

The term “choice overload” was coined by the American writer Alvin Toffler in his 1970 book Future Shock. The book was about how people were, at that point, grappling with “too much change in too short a period of time.”Toffler predicted that, as industrialization intensified, the people of the future (which is to say, us) would suffer from a “paralyzing surfeit” of choice.10

A couple of decades later, choice overload started to receive attention as a subject of psychological research. In 1995, Sheena Iyengar, one of the foremost experts on choice, conducted the famous jam study. Barry Schwartz started researching choice overload in the early 2000s and published The Paradox of Choice in 2004.

Example 1 – Smartphones and choice overload

In a 2005 TED talk about the paradox of choice, Barry Schwartz talked about how new technologies contributed to choice overload, chiefly by allowing us to carry our work around with us everywhere. It was the early 2000s, before the dawn of the iPhone, but people did have laptops and Blackberries, which were sufficient to send emails and work on presentations when not at the office. Even when we weren’t actively using these technologies, Schwartz argued that they detracted from our experience by giving us the option to. With the increase in technology, we are faced with a multitude of choices regarding our work and home life “Should I answer this cell phone call? Should I respond to this email? Should I draft this letter?’”

Now, almost two decades after Schwartz’s talk, smartphones are ubiquitous, meaning we carry thousands of ways to integrate technology into our lives The result is constant choice overload: Research has shown that merely having a smartphone within reach lowers the quality of in-person conversations, even if people aren’t using or even looking at it.11 When we have so many options at our fingertips, we constantly have the impulse to pick something else to do, which saps our attention and sabotages our relationships.

Example 2 – Cultural differences and choice

As mentioned above, choice plays a particularly important role in American culture: the freedom to make decisions for oneself is considered essential. This might be why we experience so much choice overload: whereas in the past, many decisions would have been made collectively, or made for us by experts, nowadays, the burden of choice is virtually always with the individual.

In other cultures, individual choice isn’t necessarily valued so highly, and this different approach can have a major impact on how people cope with difficult decisions. In one study, Sheena Iyengar and her colleagues compared the responses of American and French families, after they had made the difficult decision to withdraw their infant children from life support. In the US, this choice rests with the parents, but in France, doctors make the call, unless they get explicit pushback from the parents. The researchers found that French families were less angry and confused about what had happened.12 These results suggest that, contradictory to American culture, it may improve individuals’ well-being to give important choices to somebody else.

Summary

What it is

Choice overload describes how, when given more options to choose from, people tend to have a harder time deciding, are less satisfied with their choice, and are more likely to experience regret.

Why it happens

We have limited cognitive resources, so having more options to consider drains our mental energy more quickly, overwhelming us. Trying to maximize (i.e. finding the best option) also makes us prone to choice overload, as does preference uncertainty.

Example 1 - Smartphones and choice overload

By giving us so many choices about how we can spend our time, smartphones and other mobile technologies might contribute to a persistent sense of choice overload.

Example 2 - Cultural differences

While Americans prize individual choice, other cultures are more comfortable with handing off decisions to community members or experts. Research shows this might reduce the negative feelings we experience after making a difficult choice.

How to avoid it

While the number of choices presented to us isn’t controllable, we can use techniques to mitigate the overwhelming effects of too many options: set aside some dedicated browsing time, treat your choices as nonreversible, and try keeping a gratitude journal.

Related TDL articles

How to Protect an Aging Mind from Financial Fraud

As we get older, we become more susceptible to choice overload, which can in turn make us more vulnerable to fraud. This article explains, in more detail, why older adults are more likely to fall for scams, and what you can do to counteract these effects.